und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

El Amparo, Monument 1: A Re-evaluation of a "Lost" Inscribed Monument from Chiapas, Mexico

Research Note 27

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.23.rn027.en

Elisabeth Wagner (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Christian Prager (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

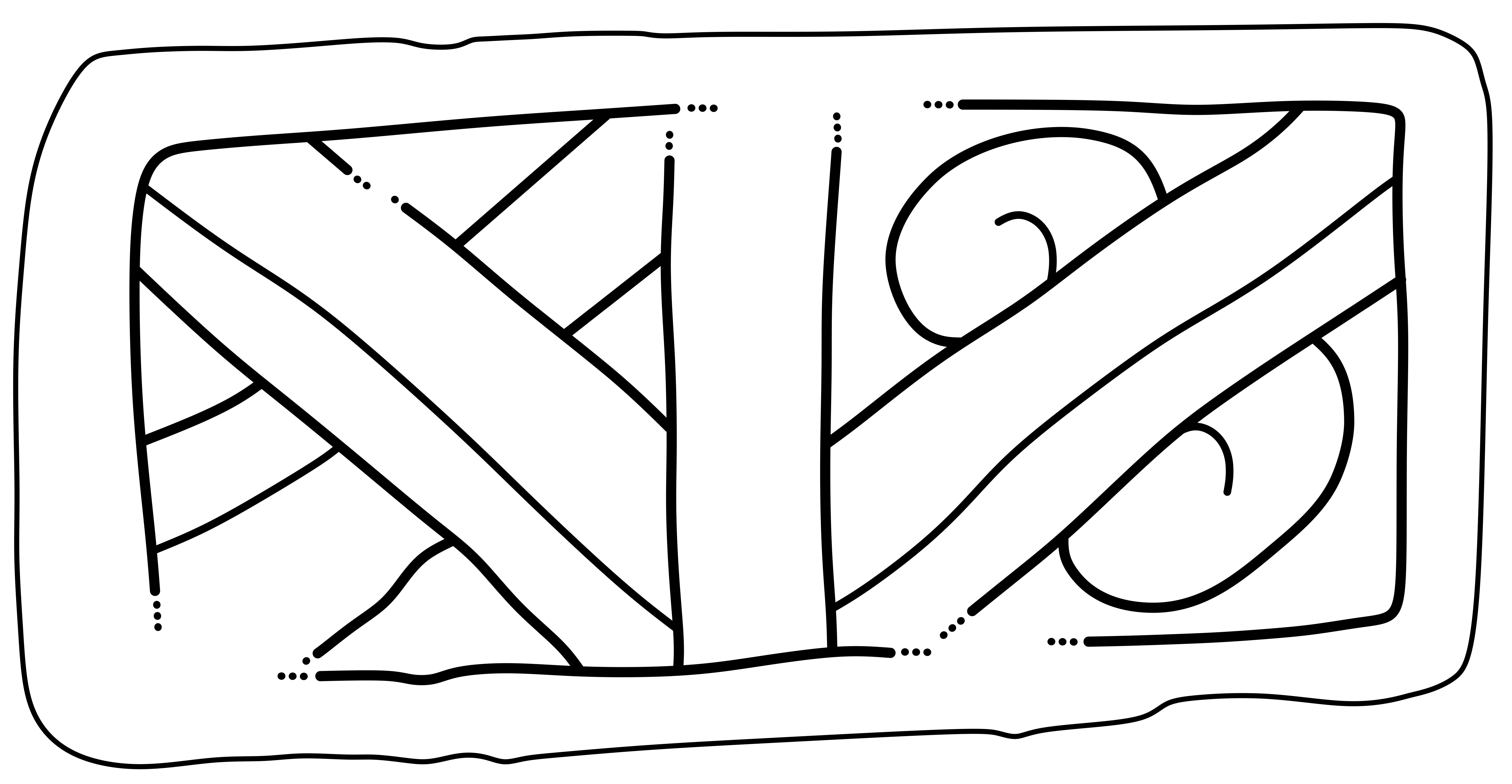

In the present note we present an inscribed monument discovered and first documented by Enrique Juan Palacios almost hundred years ago during his exploration of archaeological sites in Chiapas (Palacios 1928: 106, 107, Figs. 66, 67). Later, Richard Ceough[1], a professor of speech at the University of Michigan (Getchell 1947: 415) and archaeology enthusiast, who undertook several expeditions in Chiapas during his holidays in the years from 1943 to 1946 (Ceough 1944a, b, Ceough 1945a; Ceough and Corin 1946), rediscovered the monument in 1945, and photographed all sculptured sides of it (Figure 1a-d).

These photographs illustrated Ceough’s report to the INAH (Ceough 1945a) on his expedition in 1945 which was never officially published. In 1949, after Ceough’s sudden death in 1948, Blanche Corin, editor of Ceough’s reports, left Richard Ceough's material to the Hispanic Society of America in New York City which finally donated these materials to the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation in 1966 (Menyuk 2015: 2).

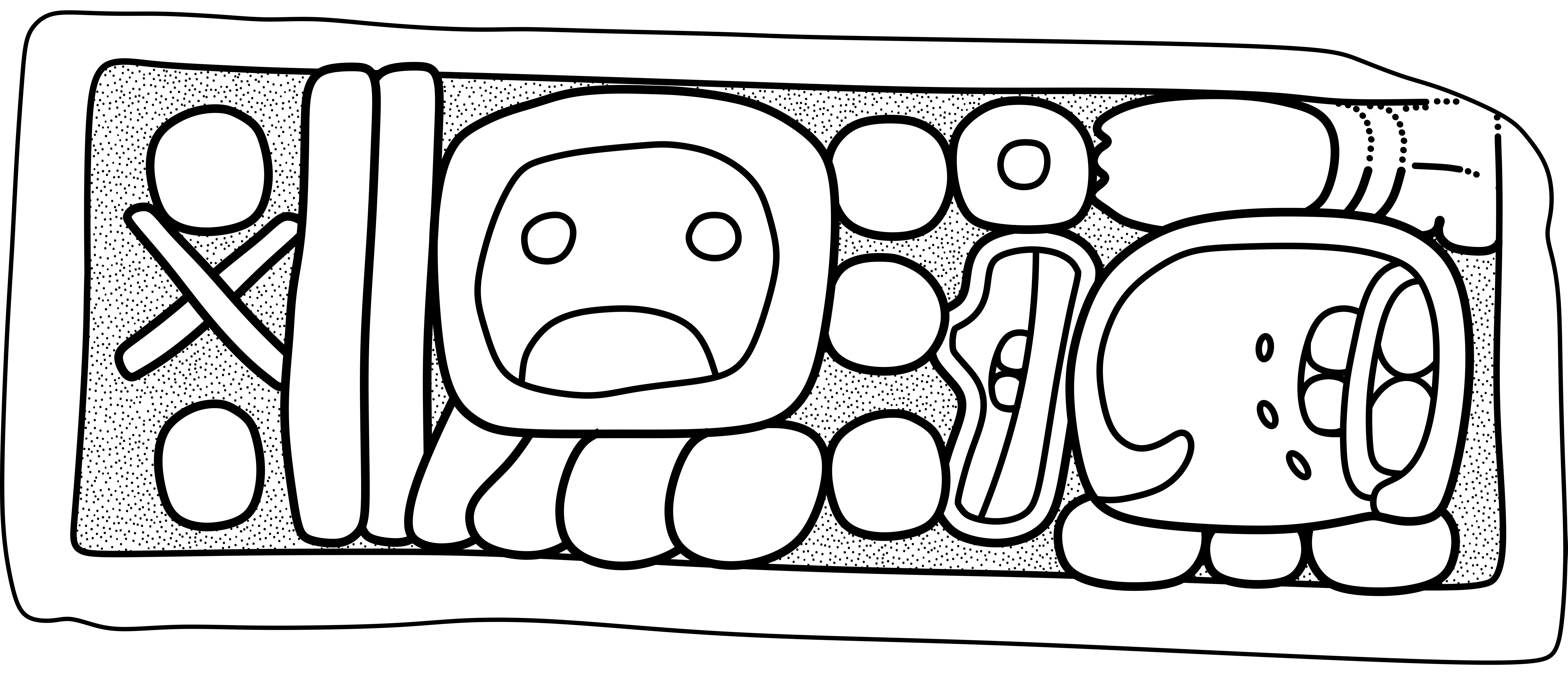

Only the recent online-publication of Ceough’s reports has made this important source on the archaeology of Chiapas available to a wider audience. The online publication of Richard Ceough’s photographs has allowed us to definitely identify the monument type, fully read the date recorded on it, discuss various aspects regarding its original context and historical implications, and prepare a new drawing that includes all sculptured surfaces (Figure 2).

|

|

|

|

Discovery and Documentation

During his visit at the finca El Amparo in 1926, Enrique Juan Palacios encountered an inscribed stone monument resting on a modern plastered masonry construction on the premises of that finca then owned by Elías Guillén (Palacios 1928: 106-107). Palacios published a drawing and a photograph of the monument (Palacios 1928: 107, Figs. 66-67). During his 1945 expedition in Chiapas, Richard Ceough (1945a: 10) visited the finca El Amparo on July 27, 1945 and photographed the three sculptured sides and the top side of the monument (Ceough 1945a: 10, Figs. 53-56). Ceough’s photograph of the monument’s front was later published by Eric Thompson (1950: Fig. 50,5). Both Palacios’ and Ceough’s photographs show the monument resting on the same masonry structure, indicating that the monument’s placement at the finca had not been changed in the 19 years between the visits of these two explorers in 1926 and 1945. So far, the authors neither could retrieve any information on the original location of the finca El Amparo, if that finca still exists, nor on the current whereabouts of the monument.

Location of El Amparo

|

|

|

|

| Figure 3. Localizations of El Amparo and Santa Elena Poco Uinic on various maps. | |

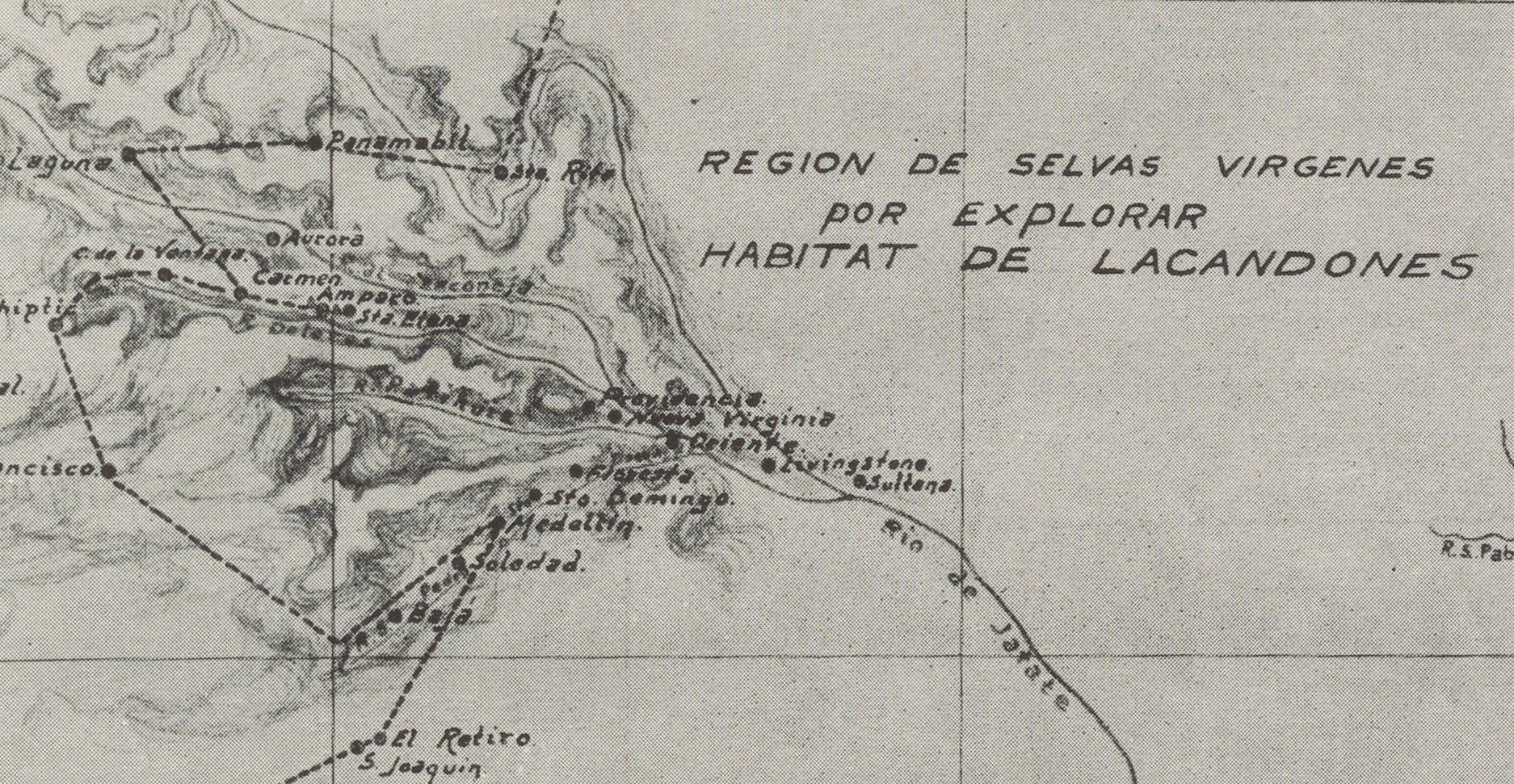

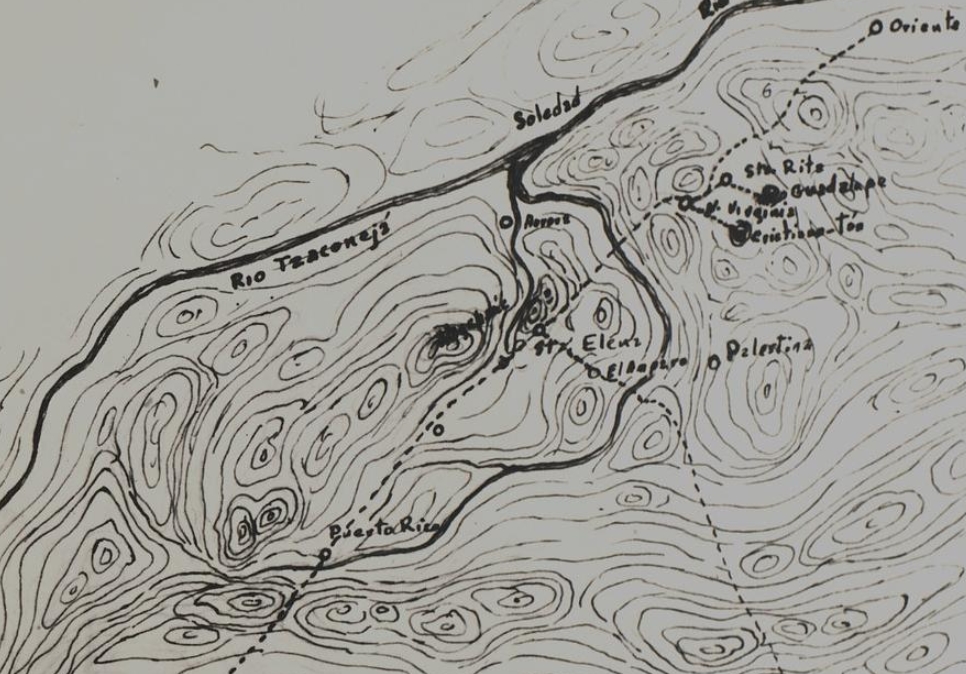

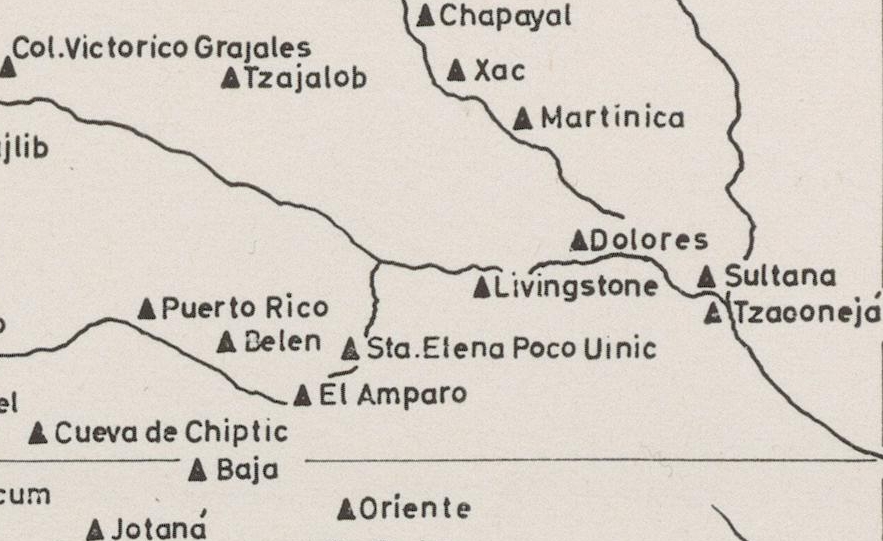

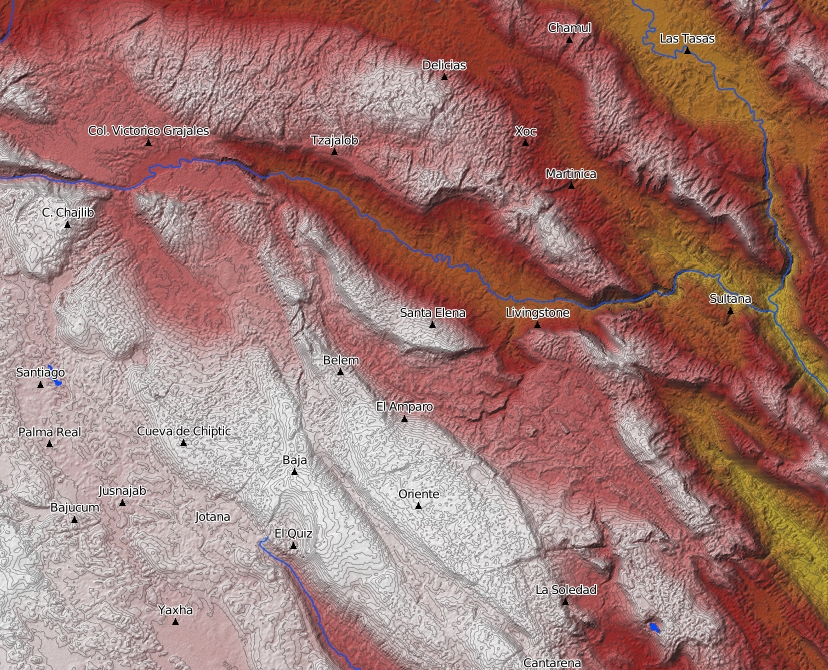

Although the location of the finca El Amparo and a potential archaeological site of the same name is indicated in various maps (Figure 3), it has so far not been located precisely by geographic coordinates. Palacios has “Amparo” in his 1928 map and Frans Blom and Gertrude Duby (1957: 231) refer to the place as “Amparo II” providing the following description: “Rancho, cerca de Sta. Helena Cafetal (Poco Uinic).” Various maps – both sketches (Ceough 1945a) and official maps (INAH 1939, Piña Chan 1967, Blom and Duby 1957, Witschey and Brown 2010, Taladoire 2015:48, Map 1; 2016: 16, Mapa 1; 2017: 144, Fig. 2) - have been published with “El Amparo” or “Amparo” marked in them. However, all these maps lack precision due to their large scale. Further, on Witschey and Brown’s map (2010) the localization of both “El Amparo” and the nearby site Santa Elena Poco Uinic differs considerably from the localizations of these two sites on the other maps. Except those on Witschey and Brown’s map, the localizations on the maps from the 1930s to 1960s and also the more recent maps published by Eric Taladoire may be based on the map published by Palacios (1928: 106-107). Unfortunately, the name “El Amparo” – neither of the finca nor an archaeological site - has not survived on any more recent official maps by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) of the region in question (INEGI ED SGM 2006, INEGI 2021). Peter Mathews, the only scholar who visited Santa Elena Poco Uinic and surroundings, more recently noted that neither one of the locations of both Santa Elena Poco Uinic and El Amparo is marked correctly in the so far published maps[2]

Since the original location and context of El Amparo, Monument 1 are not known, it is not clear if the monument’s original place, the potential site of El Amparo, existed as a separate independent site, as an eventual satellite group, or an integral part of Santa Elena Poco Uinic. However, the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions has listed it as a separate archaeological site and introduced the site code AMP (Graham 1975: 23-24; 1982: 185-187; Graham and Mathews 1999: 187-189; Fash 2012, 2016) that is also cited in other lists of Maya archaeological sites (Riese 2004, Mathews 2005, 2006-).

Description

Typological Classification and Designation

Earlier descriptions did not specify the type or function of the monument; Palacios referred to it as stone prism or “prisma de piedra” (Palacios 1928: 107) or simply as a stone (“piedra”) (Palacios 1928: 107, 135, 200), and Ceough (1945a: 10) referred to it incorrectly as “stela”. In the entry “Amparo II” in their list of archaeological remains, Frans Blom and Gertrude Duby (1957: 231) refer to the monument as a stela base with glyphs (“base de estela con glifos”). Later, both Sylvanus Morley (Morley 1948: 69) and Berthold Riese (n.d.) designated the monument as altar, obviously basing their assessments only on the images published by Palacios, respectively Thompson, and thus not knowing the remaining photographs taken by Ceough. Karl Herbert Mayer (Mayer 1984: 34) cites Palacios’ discovery of the monument and refers to it as a “rectangular stone block”. Previous designations of the monument include “C.I.M. 1766” (Morley 1948: 69), “El Amparo 1” (Thompson 1950: Fig. 50, 5), and “El Amparo, Altar 1” (Riese n.d.).

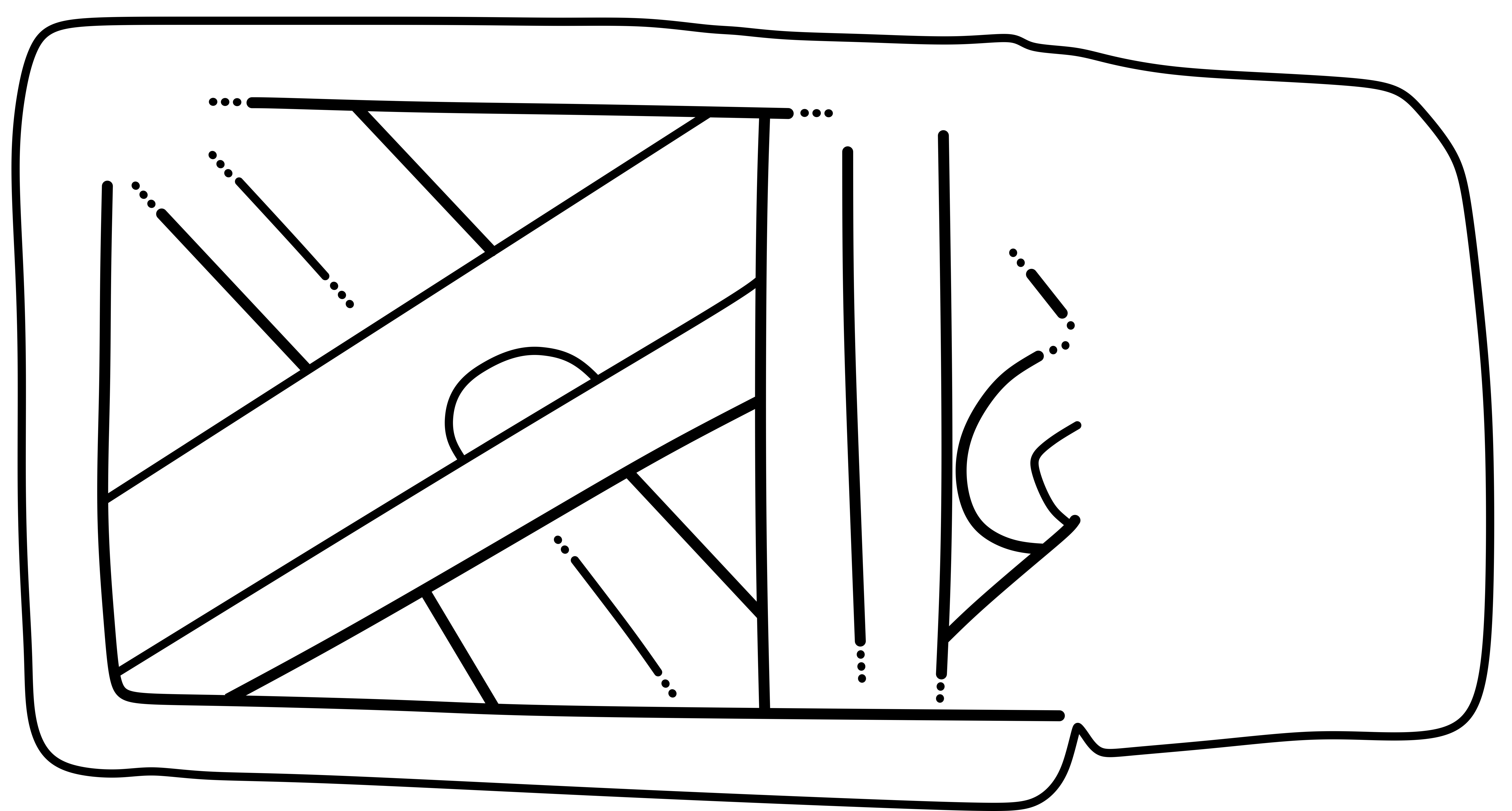

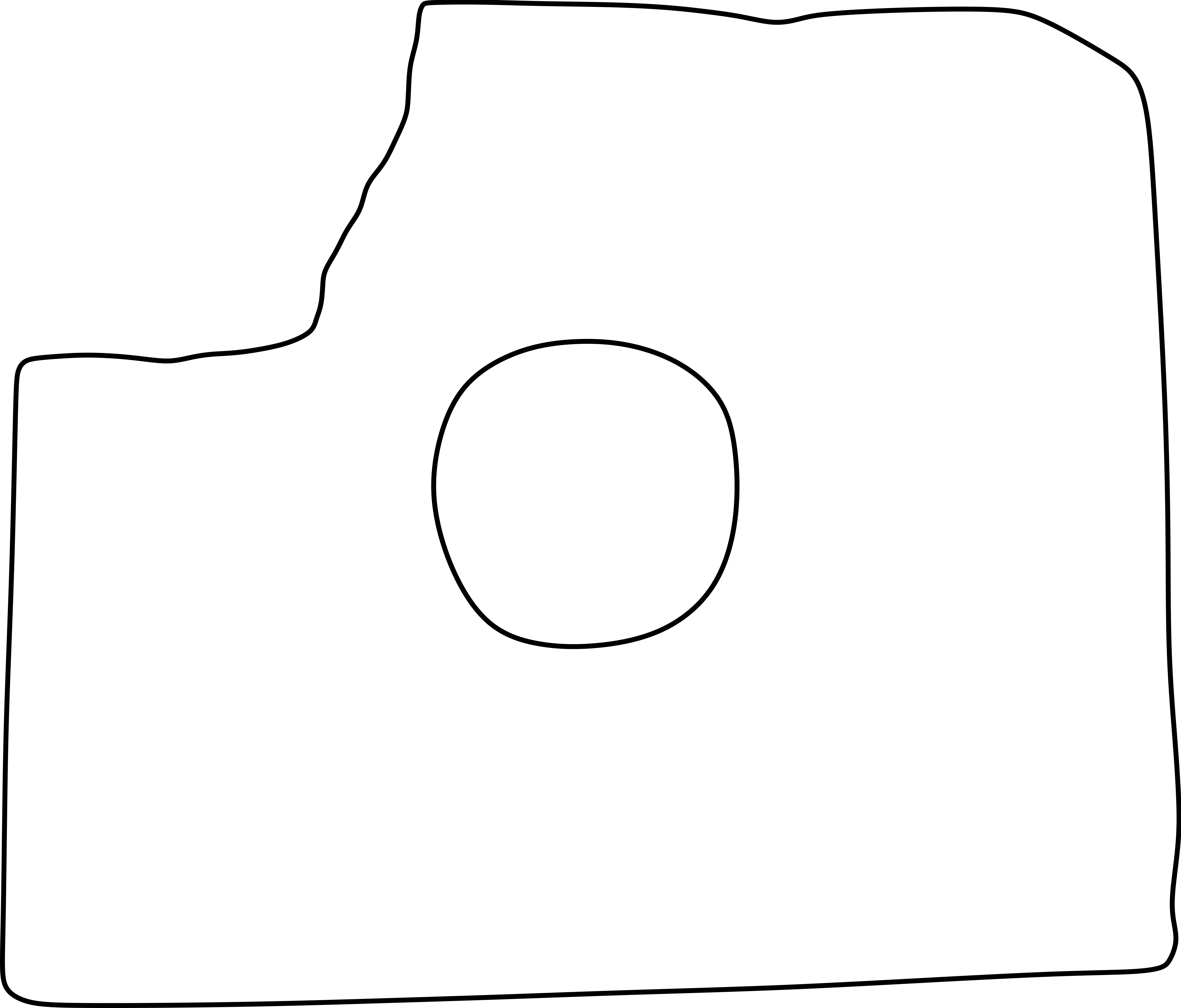

One of Ceough’s photographs (Ceough 1945a: Fig. 56) shows the top [Sic!] side[3] with a circular hole in its center and thus provides the final clue regarding the type and function of this monument: The slab format and the central hole perforating this slab identify it as a so called “stela base” as already identified by Blom and Duby (1957: 231), or – more correctly – a statue base[4], a monument type particularly known from Tonina and apparently invented by the sculptors of that site. However, since the central hole points to the monument as a statue base, the former typological classification as “altar” should not be used anymore. Therefore, we propose the neutral designation “El Amparo, Monument 1” or the abbreviation according to the standard of the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions project (cf. Graham 1975: 23-24, 1982: 185-187, Graham and Mathews 1999: 187-189) “AMP: Mon. 1”.

Dimensions

There are no exact dimensions available for the monument. Palacios provided only approximate dimensions as “una vara [approx. 84 cm] aproximada por base y alto de 0.38 c." (Palacios 1928: 107)[5]; Ceough did not mention any dimensions at all.

Material

Neither Palacios nor Ceough provided information on the material of the monument. However, assessing the surface texture of the monument’s stone and considering the rock types available in the region, it can be concluded that the material is limestone. Outcrops in the region feature deposits of Cretaceous to Paleogene (Tertiary) sandstones, mudstones (“lutite”), and limestones (cf. SGM 2006). The limestone outcrops show well defined strata of varying thickness. Slabs loosened and deposited by erosion or being quarried from such limestone outcrops provided the ideal raw material for monuments and masonry stones for the ancient Maya builders and sculptors of the region.

Condition

In 1945, at the time of Richard Ceough’s visit, the sculptured surfaces of the monument are well preserved which indicates that the sculptured sides of the monument were not exposed to the elements for most of its existence. It may have been buried or sunken into the ground rather soon after its original placement until its discovery and final deposition at the finca El Amparo in modern times. Unlike the sides, the bottom side, however, shows clear evidence of erosion which argues for the bottom having been exposed to weathering while the remaining surfaces were protected by surrounding soil. The front and the sides show mostly minor damage at the edges with the exception of a larger fragment broken off on the right side resulting in the loss of the monument’s right back corner.

Technique

The stone of the monument is cut in the shape of an approximately quadrangular slab, smoothened on all surfaces, with a circular hole in its center. It is sculptured in low-relief on three sides, including the front and the lateral sides. On the back, top, the interior surfaces of the central hole, and the bottom the stone is plain with a smoothened surface. The workmanship of the sculptured areas is quite rustic – or perhaps unfinished - with the lines of the carving and the relief ground not perfectly smoothened, and chisel marks still visible.

Archaeological Context

Unfortunately, the original location and context of El Amparo, Monument 1, and eventual features and artefacts associated with it are unknown, as are the whereabouts of the statue originally associated with it. Therefore, any chronological positioning by stratigraphic or artefactual evidence, or any attribution to a historical individual or supernatural entity impersonated by this individual is (yet) impossible. Whether this statue base was associated with a deity impersonator or a portrait of an important local ancestor/ancestral ruler can only be speculated. An association of that former statue and -base with a structure that housed the portrayed individual’s tomb and serving as an ancestral shrine cannot be ruled out.

Epigraphic and Iconographic Analysis

Inscription

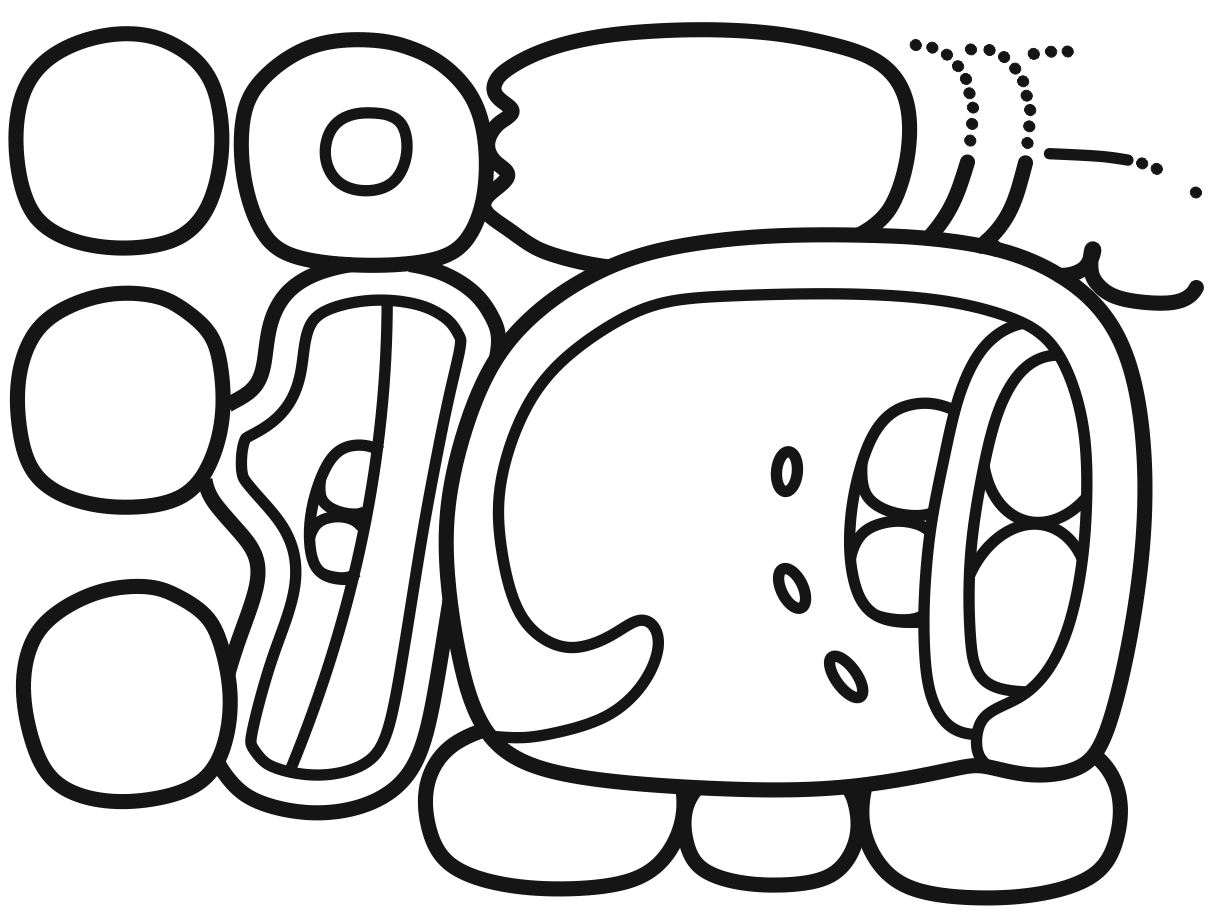

The front of the monument features a single calendar Round date, here designated with the coordinates A and B (Table 1)[6].

|

|

| 5012st.[1500bv°533st] | 5003st.87bt.[58st:186bb:74tb] |

| 12.[DAJAW] | 3.TE'.[SAK:SIHOM:ma] |

| 12-DAjaw | HUX-TE'-SAK-SIHOM-ma |

| 12 Ajaw | Huxte' saksihoom |

| 12 Ajaw = 12 Ahau | Huxte' Saksihoom = 3 Zac |

Table 1. Epigraphic analysis of the inscription of El Amparo, Monument 1 (Drawings by Christian Prager)

Iconography

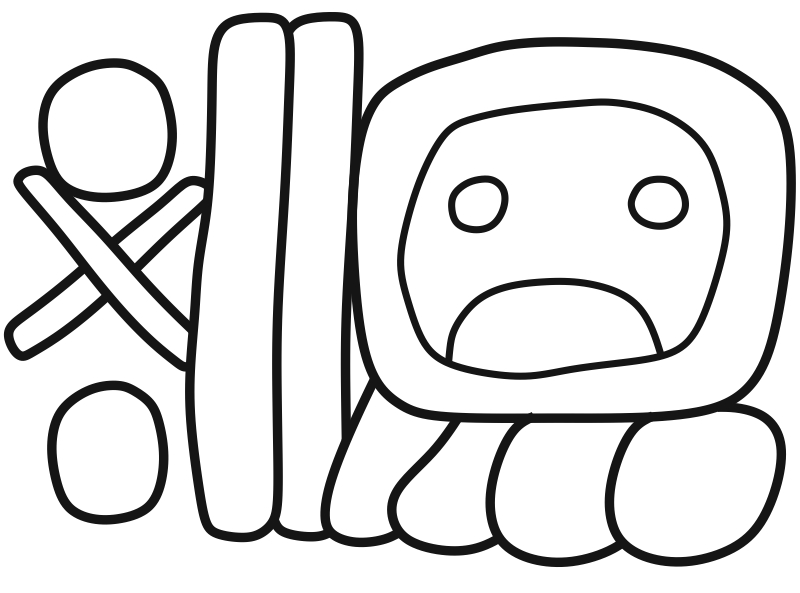

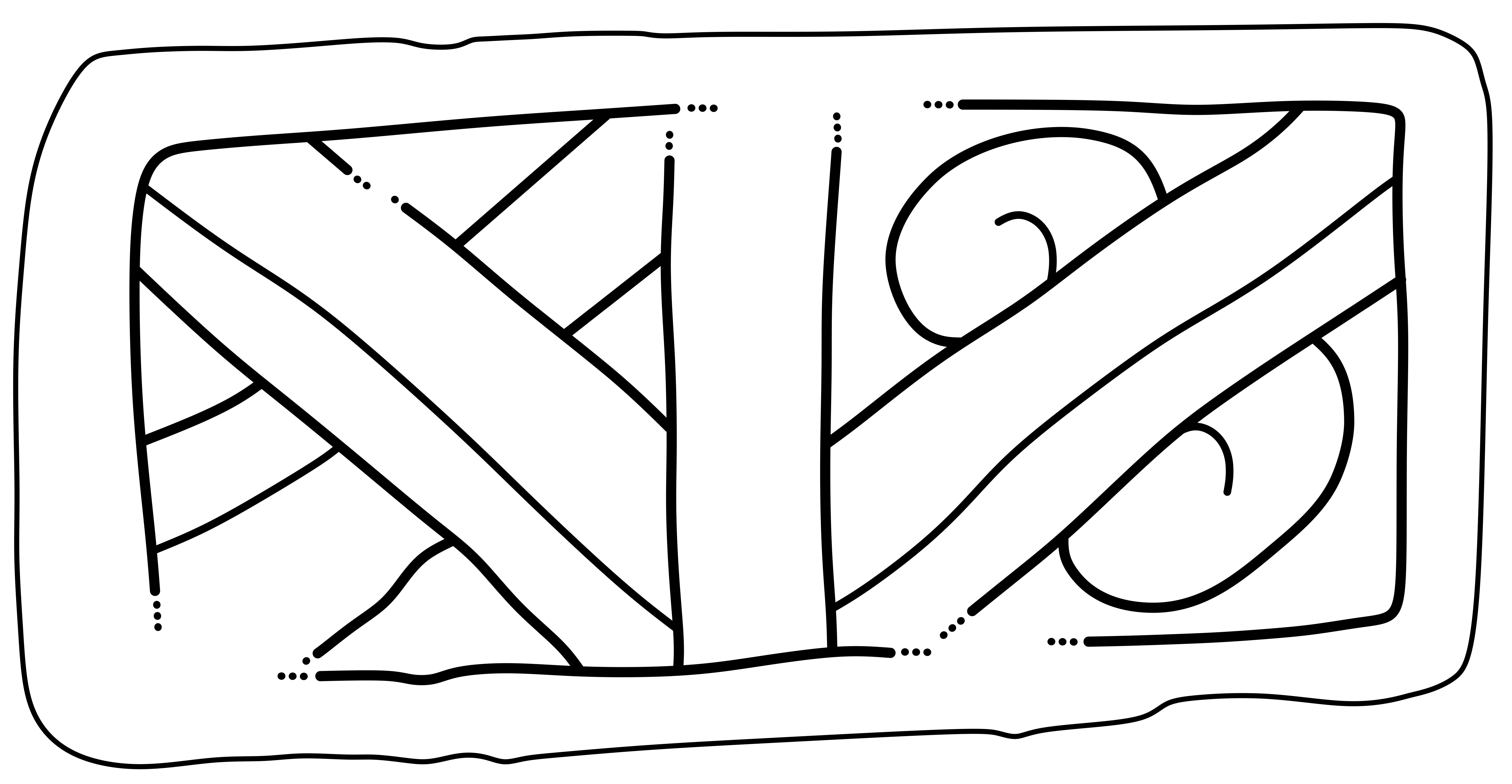

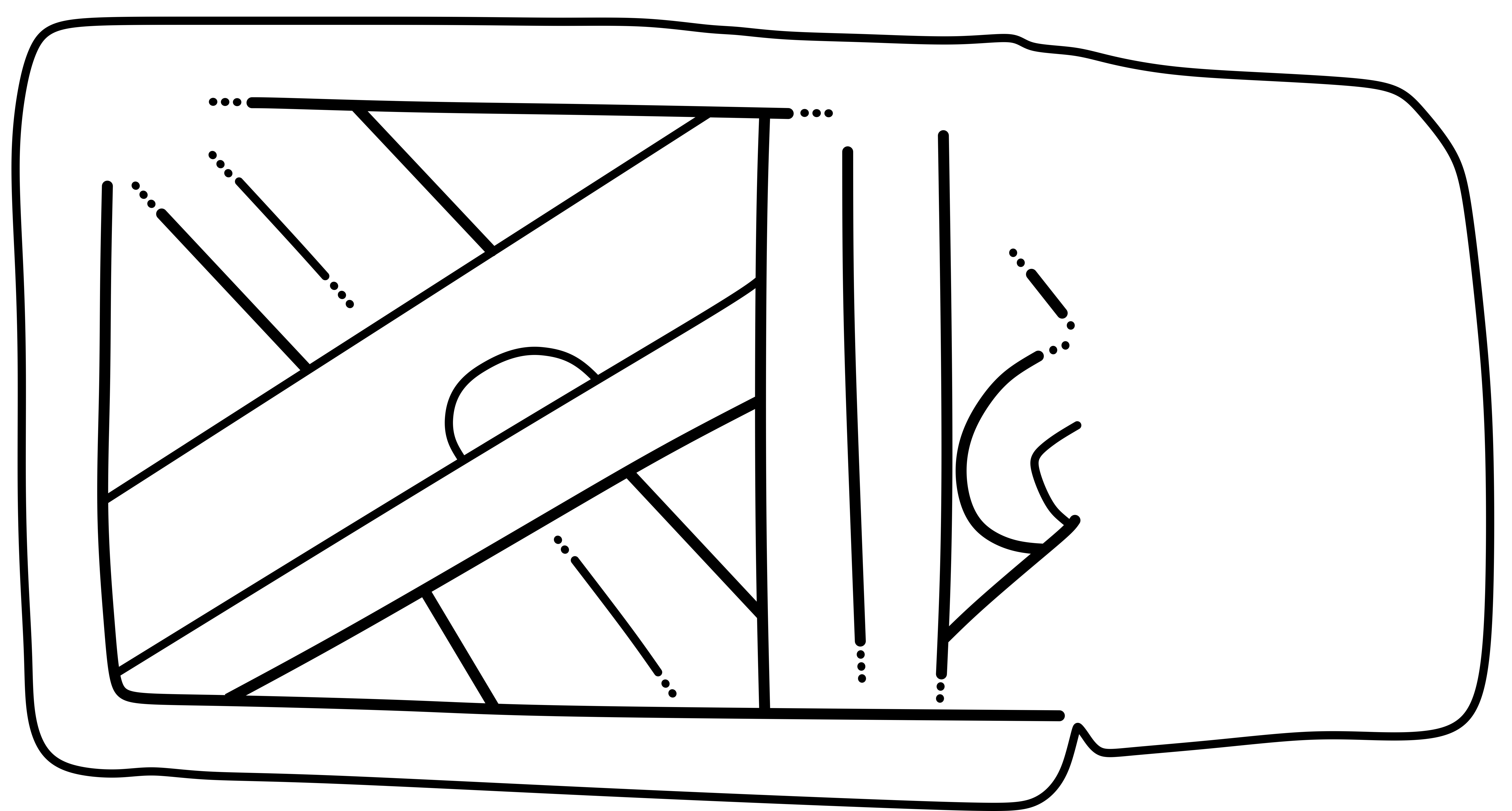

On both lateral vertical surfaces, the monument shows iconographic elements that are characteristic for skybands in Maya iconography, but rendered rather simply (Figure 4).

|

|

| Figure 4. Skyband imagery on El Ampara, Monument 1: a) left and b) right side. Drawings by Christian Prager. | |

In contrast to more elaborate renderings of skybands in Maya iconography, both the horizontal top- and bottom frames, as well as the vertical beams of the skyband on El Amparo Monument 1 lack the te’-markers. Instead, each side of the monument is divided in two pictorial fields containing each a skyband element, separated from each other by a vertical bar-motif.

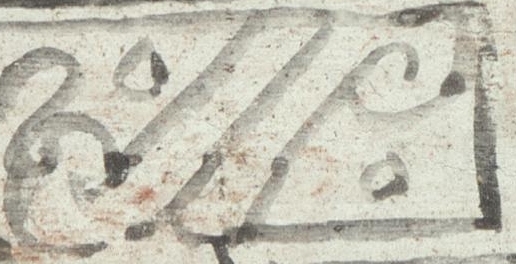

On the left side (relative to the front with the inscription), the field nearer to the front shows an iconographic motif consisting of a diagonal bar with two scrolls attached, a motif that has been listed in previous studies on Maya skybands by Beth Collea as “Opposed volutes” (Collea 1981: 218, Fig. 20.2g, 219, Table 20.1) and by John Carlson and Linda Landis as #13 in their classification scheme of skyband elements (Carlson and Landis 1985: 136-138). Carlson and Landis’ element #13 seems to be a combination of their element #12, derived from sign 561, CHAN, chan, sky, and their element #10, the Zip-Monster, in its more simplified and more abstract form (Carlson and Landis 1985: 138). In Maya iconography, the so-called Zip-Monster - equivalent to the mythic creature that was known as Xiuhcoatl “Fire Serpent” among the Late Postclassic Mexica’ - is a serpentine creature that symbolizes in particular the warm wind or "solar breath" (cf. Houston et al. 2006: 156; 157, Fig. 4.15), or radiating heat and burning in general, or the warm breath of a living being, or of objects and substances of power (Houston et al. 2006: 156). The simplified form of element #13 is known from skyband imagery in the Postclassic Maya codices (Figure 5).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dr. 44b | Dr. 53b | Dr. 54a | Dr. 55a | Dr. 56a | Dr. 56b | Dr. 57a | Dr. 57b | P. 23 | P. 24 |

|

Figure 5. Postclassic Maya illustrations of “opposed volutes”/”element #13“ in various skybands in the Codex Dresdensis (Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden) and the Codex Peresianus (Paris) (Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, images from Rosny 1888). |

|||||||||

It also resembles the symbol used later in Postclassic and Early Colonial Central Mexican/Mexica’-iconography as a symbol that had been associated by Eduard Seler with ilhuitl “day” (Tag), “festive day” (Festtag), or “sun’s orb” (Sonnenball) (Seler 1893: 93, Figs. 162, 164; 99, 105; cf. Molina 1977: 37v; Favrot Peterson 1993: 49; Carlson and Landis 1985: 127-128), but more recently proposed to represent ilhuicatl “sky” (Houston and Taube 2000: 278; cf. Karttunen 1983: 104) (Figure 6).

|

|

Figure 6. Late Postclassic central Mexican (Aztec) sculpture with representation of a sky band with the glyphs “butterfly” and ilhuitl/ilhuicatl (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Yew York, Accession # 00.5.38; https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/307638). |

However, on El Amparo, Monument 1, both scrolls of the “ilhuitl/ilhuicatl”-element are arranged in mirror image along the diagonal axis and both oriented in the same direction while the scrolls of the actual ilhuitl/ilhuicatl-element and its equivalent in the codices are oriented in opposite directions. This deviation of the sculptured design may be an error and attributable the crude style of the sculptor.

The combination of the symbol for heat and warmth and for the sky in a skyband, allude to the heat and warmth of the (sunny) sky during daylight, and thus symbolize the diurnal sky and daylight.

The element towards the back shows the “crossed bands-motif”, Collea’s “Crossbands” (Collea 1981: Fig. 20.2a, 219, Table 20.1), respectively Carlson and Landis’ element #11 (Carlson and Landis 1985: 127, 138) which is actually a representation of crossed beams as part of a roof-construction (cf. Taube 1998: 432). On the right side, the arrangement of the pictorial fields is the other way around with the crossed beams towards the front, and Carlsen and Landis’ element 13 towards the back. Here, the crossed beams feature a “te’-marker” to indicate their material as wood. However, this te’-marker is unfinished with only one “blob” instead of two ones. Altogether, the lateral surfaces of the statue base represent a simple form of a skyband.

The fact that the statue base carries motifs forming a skyband, indicates that the base symbolizes a celestial place. Like the lower part of a stela or panel with toponymic and/or topographic references and/or imagery, a statue base may allude to a specific place where the portrayed individual acts (cf. Stuart and Houston 1994). With respect to El Amparo, Monument 1, the individual represented by the statue that was originally connected with this monument as its base, was therefore intended to be located and acting at a celestial place. In ancient Maya imagery and texts, celestial places where the realm of celestial deities and deified ancestors acting in the role of celestial deities. The diurnal, and thus solar aspect of the skyband on El Amparo, Monument 1 may relate to the theme of “solar ascent” or “solar rebirth” of male (royal) ancestors (cf. Taube 2004a: 78-87, 2004b), a common theme in ancient Maya iconography in the context of elite ancestor veneration and the portraiture of royal ancestors.

Paleography and Dating of the Inscription

Palacios (1928: 107, 135, 139) puts the Calendar Round date 12 Ajaw 3 Chen into the Long Count position 9.11.13.0.0. Eric Taladoire states 9.11.0.0.0 [12 Ahau 8 Keh) as the date of the El Amparo Monument (Taladoire 2015: 58), and Lynneth Lowe (2010: 470) dates it equivalent to Tonina, Monument 101, to 10.4.0.0.0 [12 Ahau 3 Wo] without any further explanation. However, with respect to the dates proposed by Palacios and Taladoire, the paleography (filler-element in the coefficient 12) and the general style point to a later date of the monument with a terminus postquem of 9.17.0.0.0 (cf. Thompson 1950: Fig. 50,5; Riese n.d.).

Further, the rendering of the graph 87bt, representing Sign T87, TE’, functioning here as the numeral classifier te’ in the haab date, points to a late form of 87bt after 9.17.5.0.0, and particularly the late Postclassic variants of that sign in Postclassic codical texts (cf. Lacadena 1995: 103, Fig. 2.43b, 386, Fig. 6.118).

Although Palacios proposed to read the haab month name as Chen, neither Thompson (1950: Fig. 50, 5) nor Riese (n.d.) accepted Palacios' interpretation of the haab month as Chen, and thus did not attribute a Long Count position to the Calendar Round date 12 Ajaw 3 te' ? on El Amparo, Monument 1, while later on, Lowe (2010: 470) and Taladoire (2015: 58) attributed different Long Count dates, both period endings on the Tzolkin day 12 Ahau. However, a closer inspection of Ceough’s photograph (1945: Fig. 53) reveals that the haab is Zac. Considering the mentioned paleographic and stylistic characteristics, possible Long Count positions for the Calendar Round 12 Ahau 3 Zac could be 9.17.10.13.0, 10.0.3.8.0, or 10.2.16.3.0.

Historical Context

Given that none of the possible Long Count dates are period endings, the actual date seems to commemorate some historical event, such as biographical events in the life of a king or other (local) noble. This event may have taken place in the biography of the individual – perhaps some local lord - originally portrayed or referred by the now missing statue to which the statue base once belonged. Depending on the original context of the monument, such an event could have been any kind of biographic event, e.g., accession, accession anniversary, death, burial, etc.

When comparing the style of El Amparo Monument 1 to that of the inscribed monuments of nearby Santa Elena Poco Uinic which feature an elegant full-blown Late Classic sculptural style around 9.18.0.0.0, and considering the possibility that the yet to be identified site of El Amparo was part of Santa Elena Poco Uinic’s sphere, both paleography and the style of iconographic elements rather support a post-9.18.0.0.0 date, and thus the two later Long Count positions as feasible dates for the El Amparo monument.

With respect to the chronological positioning of El Amparo, Monument 1, it is worth to note that the inscribed Late Classic monuments of nearby Santa Elena Poco Uinic do not feature any characteristics that would associate them with Tonina (cf. Mathews 2006-, Taladoire 2015: 58, 59), but rather with Chinkultic and Tenam Puente as neighbors and perhaps adversaries of Tonina (Taladoire 2017: 161-162).

When considering the existence of at least ten unsculptured statue bases in the region of Santa Elena Poco Uinic as stated by a “Señor Figueroa” in a personal communication to Richard Ceough on July 27, 1945 (Ceough 1945a: 10) and also observed by Peter Mathews in 1980 (Mathews 2006-, Taladoire 2015: 59, the introduction of this monument type may have been the result of a change in socio-political affiliation of Tonina towards the kingdom and region of Santa Elena Poco Uinic sometime after 9.18.0.0.0 (Stela 3) and the date of El Amparo, Monument 1. Unfortunately, there is no further contextual information available for any of the statue bases with respect to stratigraphic position, associated statues, features, and artefacts that would allow their chronological positioning.

Similarly, the occurrence of Tonina-format sculptures, namely statues, statue bases, and (tenoned) captive figures are attested elsewhere, both in the Chiapas Highlands at Tenam Puente (cf. Laló Jacinto and Aguilar 1993, Earley 2015: 74-96) and elsewhere. Eric Taladoire (2015: 58) notes that the existence of Tonina-format sculpture “is quite insufficient to consider seriously an influence from Toniná. Such similarities are not truly significant since, as Baudez noted (1999), several sculptural characteristics of Toniná (such as) can be found at other sites: Tenam Puente itself (st. 2), but also Chuctiepa (statue) and Tortuguero (st. 3), that undoubtedly belonged to the Palenque polity.”

Arguing in a similar direction, Caitlin Early states “that style can reflect interaction between sites—but it is not a rote marker of subordination. [… 93…] It is clear […] that Maya cities in this area recognized the artistic styles of their neighbors and used that style in a variety of ways.” (Earley 2015: 92, 93).

Earley further notes with respect to the Tonina style monuments at Tenam Puente, that “We must consider […] a scenario in which the stylistic connections between Toniná and Tenam Puente represent local emulation of a well-known style rather than a direct relationship between the two sites. Perhaps the elites of Tenam Puente sought to represent themselves and their history according to the precepts of the Toniná style, associating themselves with divine kingship and trumpeting their geopolitical supremacy using the same vocabulary of forms.” (Earley 2015: 94). These observations and resulting statements by Caitlin Earley with respect to Tenam Puente (Earley 2015: 92-94), can be regarded as also valid for the occurrence of Tonina style sculptures at Santa Elena Poco Uinic and El Amparo.

In terms of an apparently late occurrence of Tonina-style sculptures at Tenam Puente, Santa Elena Poco Uinic, El Amparo, and elsewhere, it is worth to note that at both Tonina and the Ocosingo Valley, a considerable change is evident by the change of ceramic spheres from those of the Maya Lowlands to the Chenek ceramic sphere of the Chiapas Highlands during the Terminal Classic, corresponding to the Imix/Chenek phase of Tonina chronology (Taladoire 2017: 167). This change of the ceramic sphere in the Ocosingo valley has earlier been interpreted as the result of a violent invasion from northern Chiapas that resulted in the destruction of Tonina’s royal seat and the killing of its dynasty around 909AD (Taladoire 2017: 167). However, the revision of Tonina’s chronology, based on epigraphic evidence (Mon. 101 and 158) and associated ceramics, puts the Ixiim/Chenek transition already to around 840AD during the reign of Uh Chapaat (Taladoire 2017: 153-154).

On the background of this change of Tonina’s ceramic sphere and apparent orientation towards the Chiapas Highlands beginning around 840AD, one of the possible dedication dates of El Amparo, Monument 1, the date 10.0.3.8.0 (6.8.833/2.8.833) would fit very well into the Imix/Chenek-transitional period. Whether dedicated on 10.0.3.8.0, or even later on 10.2.16.3.0 during the Chenek phase, El Amparo, Monument 1 would prove that the adoption of cultural traits did not occur only from the Chiapas Highlands towards Tonina and the Ocosingo valley, but also the other way around, i.e. sites in the Chiapas Highlands adopting a sculptural format originating from Tonina. However, due to the uncertain date of El Amparo, Monument 1, the lack of archaeological and epigraphic evidence from Santa Elena Poco Uinic and El Amparo, the nature and development of the socio-political relations between Tonina and the region of Santa Elena Poco Uinic-El Amparo and beyond is still unclear. At present, we can only hope for future archaeological investigations and eventual finds of more inscriptions in this area to solve these issues.

Acknowledgements

At first, we would like to thank Nathan Sowry, Reference Archivist, Smithsonian, National Museum of the American Indian, Cultural Resources Center for supplying us with high-resolution scans of Richard Ceough’s photographs of El Amparo, Monument 1, and for granting us permission to use and publish these photographs in the present Research Note. During various e-mail-discussions, Peter Mathews, Angel Sánchez Gamboa, Alejandro Sheseña, and Eric Taladoire provided us with useful information regarding the correctness of previous localizations of Santa Elena Poco Uinic and the finca El Amparo, former ownership of the finca El Amparo, and the current general situation in the region of Chiapas where these sites are located.

References

Anonymous

1928 Degrees Conferred on 2,759 Students of N.Y. University. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, New York, Wednesday, June 06, 1928: 29. Electronic document. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/16348350/1928-goodman-graduate/

Blom, Frans and Getrude Duby

1957 La Selva Lacandona: Andanzas arqueológicas. Segunda parte. México, D.F.: Editorial Cvltvra.

Ceough, Richard

1944a The Temple of the Thousand Steps at Agua Azul. Suitland: National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution. Electronic Document. https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/components/sova-nmai-ac-067-ref20?destination=archives/sova-nmai-ac-067

1944b Informal Report of the Exploration of Agua Azul and the Valley of the Lost Desires, Summer 1944. Suitland: National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution. Electronic Document. https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/components/sova-nmai-ac-067-ref22?destination=archives/sova-nmai-ac-067

1945a Informal Report on the Exploration of New Virginia, Santa Elena, Agua Azul and Chincultic, Summer 1945. Suitland: National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution. Electronic Document. https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/components/sova-nmai-ac-067-ref23?destination=archives/sova-nmai-ac-067

1945b The Temple of a Thousand Steps: "Ladder to Heaven" built by Mayan Indians 1,500 Years Ago Shows Skill of Primitive Engineers. Popular Science Monthly July: 108-111, 206.

Ceough, Richard, and Blanche Corin

1946 Untitled: Incomplete Report of the Exploration of Chiapas, Mexico. Suitland: National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution. Electronic Document. https://americanindian.si.edu/collections-search/archives/components/sova-nmai-ac-067-ref24?destination=archives/sova-nmai-ac-067

Collea, Beth A.

1981 The Celestial Bands in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. In Archaeoastronomy in the Americas, edited by Ray A. Williamson, 215-231. Los Altos: Ballena Press; College Park: Center for Archaeoastronomy.

Earley, Caitlin Cargile

2015 At the Edge of the Maya World: Power, Politics, and Identity in Monuments from the Comitán Valley, Chiapas, Mexico. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Texas, Austin. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/39686

Fash, Barbara

2012 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Program: Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions: Site Codes. Electronic Document. http://peabody.harvard.edu/files/cmhi/CMHI_SiteCodes_FINAL_2012_forWeb.pdf[2015-04-19T11:52:13Z]

2016 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Program: Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions: Site Codes. Electronic Document. https://www.peabody.harvard.edu/files/cmhi/CMHI_SiteCodes_FINAL_2016.pdf[2016-12-08T21:14:47Z]

Favrot Peterson, Jeanette

1993 The Paradise Garden Murals of Malinalco: Utopia and Empire in Sixteenth-Century Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Houston, Stephen D., David Stuart, and Karl Taube

2006 The Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among the Classic Maya. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Getchell, Charles Munro

1947 In memoriam. Quarterly Journal of Speech 33(3): 415-416. DOI 10.1080/00335634709381327.

Graham, Ian

1975 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volume 1: Introduction. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

1982 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volume 3, Part 3: Yaxchilan. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

Graham, Ian, and Peter Mathews

1999 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volume 6, Part 3: Tonina. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

Houston, Stephen, and Karl Taube

2000 An Archaeology of the Senses: Perception and Cultural Expression in Ancient Mesoamerica. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 10(2): 261-294.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI)

2021 Mapas Municipales de Chiapas, Actualización 2021: Altamirano - Mapa Municipal. Tuxtla Gutiérrez: Secretaría de Hacienda, Gobierno de Chiapas, Subsecretaría de Planeación, Dirección de Información Geográfica y Estadística, Departamento de Geografía; Comite Estatal de Información Estadística y Geográfica. https://www.ceieg.chiapas.gob.mx/productos/files/MAPASMUN/004.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH)

1939 Atlas Arqueológico de la República Mexicana. Publicación 41. México: Instituto Panamericano de Geografía Historia.

Karttunen, Frances E.

1983 An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Kramer, Gerhardt and Salo K. Lowe

1940 Map of the Archaeological Sites in the Maya Area, Scale 1:500,000. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University.

Laló Jacinto, Gabriel, and María de la Luz Aguilar

1993 El proyecto arqueológico Tenam Puente. Cuarto Foro de Arqueología de Chiapas, 151-161. Tuxtla Gutiérrez: Gobierno del Estado de Chiapas.

Lowe, Lynneth S.

2010 Chinkultic. In Guía De Arquitectura Y Paisaje Mayas - The Maya: An Architectural and Landscape Guide, edited by Maria D. Gil Pérez, José Rodríguez Galadí, and Patricia Aguila Flores, 468-470. Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; Sevilla: Consejería de Obras Públicas y Vivienda.

Mathews, Peter

2005 Who's Who in the Classic Maya World. Electronic Document. undefined. http://research.famsi.org/whos_who/sitenames_codes.htm[2015-10-15T14:48:22Z]

2006- The Maya History Project: Deciphering Classic Maya Dates. Manuscript.

Mayer, Karl Herbert

1984 Maya Monuments: Sculptures of Unknown Provenance in Middle America. Maya Monuments 3. Berlin: Verlag Karl-Friedrich von Flemming.

Menyuk, Rachel

2015 Richard Ceough Papers. Suitland: National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution. Electronic document. https://sirismm.si.edu/EADpdfs/NMAI.AC.067.pdf

Molina, Alonso de

1977 Vocabulario en lengua Castellana y Mexicana y Mexicana y Castellana. México D.F.: Editorial Porrúa.

Morley, Sylvanus G.

1948 Check List of the Corpus Inscriptionum Mayarum and Check List of all Known Initial and Supplementary Series. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, the Division of Historical Research.

Palacios, Enrique J.

1928 En los confines de la selva lacandona: exploraciones en el estado de Chiapas, Mayo-Agosto 1926. Contribución de Mexico al 23 Congreso de Americanistas. México D.F.: Talleres Gráficos de la Nación.

Piña Chan, Román

1967 Atlas Arqueológico de la República Mexicana, 3: Chiapas. México D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Prager, Christian, and Sven Gronemeyer

2018 Neue Ergebnisse in der Erforschung der Graphemik und Graphetik des Klassischen Maya. In: Ägyptologische “Binsen”-Weisheiten III: Formen und Funktionen von Zeichenliste und Paläographie [Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Abhandlungen der Geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse, 15], edited by Svenja A. Gülden, Kyra V. J. van der Moezel and Ursula Verhoeven-van Elsbergen, 135–181. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Riese, Berthold

n.d. Maya Inschriften Dokumentation (MID). Unpublished Archive. Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya.

2004 Abkürzungen für Maya-Ruinenorte mit Inschriften. Wayeb Notes 8: 1-21.

Rosny, Léon de

1888 Codex peresianus: manuscrit hiératique des anciens indiens de l’amérique centrale, conservé à la bibliothèque nationale de Paris, uncolored. Bureau de la Société Americaine, Paris.

Seler, Eduard

1893 Die mexikanischen Bilderhandschriften Alexander von Humboldt's in der Königlichen Bibliothek zu Berlin. Berlin: Königliche Bibliothek.

Servicio Geológico Mexicano (SGM)

2006 Carta Geológico-Minera – Las Margaritas E15-12 D15-3. Servicio Geológico Mexicano. https://mapserver.sgm.gob.mx/Cartas_Online/geologia/114_E15-12-D15-3_GM.pdf

Stuart, David, and Stephen Houston

1994 Classic Maya Place Names. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology 33. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Taladoire, Eric

2015 Towards a Reevaluation of the Toniná Polity. Estudios de Cultura Maya 46: 45-70.

2016 Las bases económicas de una entidad política maya: el caso de Toniná. Estudios de Cultura Maya 48: 11 – 37.

2017 El territorio de Tonina, Chiapas. Journal de la Société des Américanistes 103(2): 141-173.

Taube, Karl A.

1998 The Jade Hearth: Centrality, Rulership, and the Classic Maya Temple. In: Function and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture, edited by Stephen D. Houston, 427-478. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections.

2004a Flower Mountain: Concepts of Life, Beauty, and Paradise among the Classic Maya. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 45: 69-98.

2004b Structure 10L-16 and Its Early Classic Antecedents: Fire and the Evocation and Resurrection of K'inich Yax K'uk Mo'. In: Understanding Early Classic Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer, 265-295. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Thompson, J. Eric S.

1950 Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. An Introduction. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 589. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C.

Witschey, Walter R. T., and Clifford T. Brown

2010 The Electronic Atlas of Ancient Maya Sites. http://www.mayamap.org/

Footnotes

- Biographic summary after Menyuk (2015), Anonymous (1928), and Getchell (1947): Dr. Richard Ceough was born Albert J.C. Kretzmann in Hudson, New York in 1898. Very involved in the theatre, "Richard Ceough" was most likely taken as a stage name sometime in the 1920s or 1930s. Ceough graduated from New York University in 1922, where he also completed his M.A. in 1928 (Anonymous 1928: 29) and later his Ph.D. as well. In 1929, Ceough appeared in several performances on the stage and spent a year teaching at NYU. In 1930, Ceough joined the faculty of the City College of New York as Assistant Professor of public speaking. While at CCNY, Ceough founded the college's theatre workshop and was director of it until his sudden death in 1947 at the age of 48 from coronary thrombosis. Richard Ceough also served as editor of the Theatre Annual from its founding in 1943. In 1940, Ceough took his first trip to the Comitan region of Mexico. In 1942, Ceough returned to the Comitan region during his summer vacation and began taking part in yearly archaeological expeditions with Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History. In May of 1944, Ceough completed his first report detailing his work in the 1943 season at the "Temple of a Thousand Steps," a structure overlooking Agua Azul at Chinkultic in Chiapas, Mexico. In subsequent years, Ceough presented two more informal reports on his work in Agua Azul and other areas in the Comitan region as well as publishing an article in Popular Science on Chinkultic (Ceough 1945b). Ceough passed away suddenly in his office at the City College of New York on January 9, 1947. His report from July and August of 1946 was completed and submitted posthumously to the National Institute of Anthropology and History by Blanche Corin with assistance from Javier Mandujano y Solorzano. In 1949, Corin left Ceough's material to the Hispanic Society of America in New York City which later donated these materials to the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation in February of 1966.

- Peter Mathews, e-mail communication, October 28, 2022.

- The caption to Fig. 56 in Ceough’s reports says “Top”. However, the right side (seen from the inscribed front) shows the area were the right back corner is broken off (Ceough 1945a: Fig. 55). Thus, Fig. 56 does not show the monument’s top, but its bottom side.

- We prefer the term statue base, since the monuments associated with them are actual statues, i.e. anthropomorphic figures sculptured in the full round. Stelae which are defined as upright standing sculptured slabs, are not associated with the particular type of monument discussed in this paper.

- It seems that Palacios or the typesetter made a spelling error, and intended to write either 0.38 m or 38 cm. Considering the proportions of the monument, a height of 38 cm appears to be consistent with a width of about 1 vara (about 84 cm).

- As part of our work on a new catalogue of Maya signs and their graphs, we are currently evaluating and revising Thompson’s Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs (1962). We are critically scrutinizing his system with the help of his original grey cards and supplementing it with signs that were not included in Thompson’s original catalogue. Despite its known shortcomings and incompleteness, his catalogue is still regarded as the standard work for Maya epigraphers, which is why we adopt Thompson’s nomenclature while removing misclassifications and duplicates, merging graph variants under a common nomenclature, and adding new signs or allographs to the sign index in sequence, starting with the number 1500. Allographs are also further organized with the help of newly defined classification and systematization criteria, which we described in detail in Prager and Gronemeyer (2018). Basically, many graphs of Maya writing can be divided into two or more segments along their horizontal and vertical axes. These segmentation principles are designated by a two-letter code that is suffixed to the sign number.