und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

The Logogram A' "Thigh" in Maya Writing

Research Note 29

July 12, 2024

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.24.rn029.en

Nikolai Grube (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Christian M. Prager (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Elisabeth Wagner (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Guido Krempel (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

|

|

|

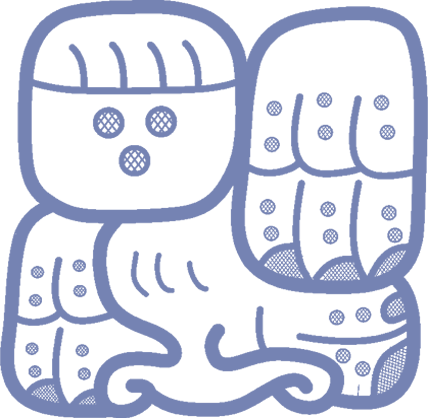

Figure 1. The sign T358 and its two graph variants 358st (one leg) and 358md (two legs) representing the logogram A' "thigh" (Drawings by Christian Prager). CC-BY 4.0 Christian Prager. |

|

In this brief article, we propose a reading for a glyph depicting a pair of bent legs, or a kneeling headless human lower body, corresponding to T358 in the Thompson catalog (Thompson 1962), as well as 358st and 358md in our Thompson-based catalog (Figure 1)[1]. It is referred to as HTB in the Macri and Looper catalog (2003) and HL6 in the online catalog of the Maya Hieroglyphic Database (Looper and Macri 1991–2024). Although the glyph appears in only a limited number of contexts, it has already received attention in previous scholarship (see especially Bíró, MacLeod, and Grofe 2014:172-173, who are also suggesting the reading A' for the logogram T358).

|

|

|

|

Figure 2. The context of the hieroglyphic compound ya-hi-358 on an unprovenanced Early Classic jade celt (Drawing by Nikolai Grube after Berjonneau et al. 1985: 220, Fig. 331). CC-BY 4.0 Nikolai Grube. |

Figure 3. The hieroglyphic compound ya-hi-358md on Tikal Stela 31 (Drawing by Nikolai Grube after Jones and Satterthwaite 1982: Figure 52). CC-BY 4.0 Nikolai Grube. |

Figure 4. The context of the hieroglyphic compound ya-hi-358-ya on Tikal Stela 40, E10-F12 (Drawing by Nikolai Grube after Valdés et al. 1997: 40). CC-BY 4.0 Nikolai Grube.

|

Federico Fahsen (1987) was the first to highlight the sign on Tikal's Stelae 12 and 31. Drawing parallels with other depictions of kneeling bodies in scenes of auto-sacrifice, he interpreted the sign as a reference to genital self-sacrifice. He, along with Linda Schele (1991), later suggested the reading YAH, meaning "wound," based on the identification of the prefix ya on Stelae 12 and 31 from Tikal preceding the logogram (see also Schele and Grube 1994: 84). However, this interpretation is not plausible in many contexts, particularly since another sign more convincingly reads as the logogram YAH, meaning "wound" (Beliaev and Houston 2020; Grube 2020).

In analyzing the syntax of Tikal's Stelae 12 and 31, one of the authors (Grube) observed that, when combined with the syllables ya and hi, the sign introduces subordinate sentences (Grube 1999). In the Maya Hieroglyphic Database, Matthew Looper and Martha Macri propose a reading of YAH for the sign and interpret the compound with the prefixed ya and hi syllables as an adverbial expression, drawing on the Cholan term ya’i, meaning “and then” (Looper and Macri 1991–2024).

Even if these various observations align, a convincing reading of the sign T358 remains elusive. The sign T358 appears a total of six times in the inscriptions with the syllable hi. In five instances, it is preceded by the syllabogram ya (Figures 2-6). The syllable hi, inserted into the lap of the kneeling body, can appear either in the full variant 186bv (Figures 2, 3, 6) or in the variant with the personified "Cauac" sign 186hc (Figure 5).

|

|

|

|

Figure 5. The hieroglyphic compound ya-hi 358md on Tikal, Stela 12 (Drawing by Nikolai Grube, after Jones and Satterthwaite 1982: Figure 18). CC-BY 4.0 Nikolai Grube. |

Figure 6. The context of the hieroglyphic compound ya-hi-358 on Caracol, Stela 6, A11-C13 (Drawing by Nikolai Grube). CC-BY 4.0 Nikolai Grube. |

Figure 7. The context of the hieroglyphic compound ya?-hi-358 on Caracol, Altar 21 (Drawing by Stephen D. Houston, cited from Chase 1991: Fig. 2). All rights reserved. |

To understand the hieroglyph ya-hi-358, it is essential to examine the syntactic position in which this sign combination appears. In six contexts, it is written before a verb: an unprovenanced Early Classic jade celt (Berjonneau et al. 1985: 220, Fig. 331) (Figure 2) shows the logogram before the verb CHOK-wi, interpreted as a transitive root with an antipassive suffix ("he scatters/throws"). On Tikal's Stela 31 (Figure 3), the ya-hi-358 hieroglyph appears before the derived intransitive verb OCH-HA-ja, ochhaj, "he water-entered," which signifies the death of Chak Tok Ich'aak II. Another instance is found on Tikal's Stela 40 (Figure 4), where the hieroglyph seems to precede a verb, possibly K'AL-ja or K'AL-HUUN-ja, "it is tied (the headband?)." On Tikal's Stela 12 (Figure 5), the ya-hi-358 hieroglyph is placed before tz'a-pa-ja u-LAKAM-TUUN-ni-li, tz'a[h]paj u lakamtuunil, "it is erected the big stone." The occurrence on Caracol's Stela 6 (Figure 6) is less clear at first glance. Here, the hieroglyph appears in a sentence about Yajaw Te’ K’inich presenting the ajaw huun, the royal headdress, to his son on the date 9.8.5.16.12 (June 26, 599; Houston, pers. communication 1993; Grube 1994: 106; Martin and Grube 2008: 90). The ya-hi-358 hieroglyph is placed in front of a verb, which in turn is written before the object ajaw huun. The verb consists of the syllable ya, an unknown sign, and the syllable wa. Given the context of passing an object, it is likely that the hieroglyph writes the transitive verb y-ak'-aw, "he gives it." The main sign of the verb shows a bird’s head with some spots or warts on it, likely representing a turkey. David Stuart has provided evidence that the turkey head is read as AK’, based on the noun ak’ or ak’ach, “turkey hen” (Stuart 2020). In this context, the ya-hi-358 hieroglyph stands before a transitive verb. Finally, the logogram is also found on Caracol's Altar 21 (Figure 7), though the following verb is badly damaged. Remarkably, in this case, the ya prefix seems to be absent.

The position of the ya-hi-358 hieroglyph immediately before verbs restricts the word classes it represents, limiting it to either an adverb or a conjunction. Another crucial observation regarding its syntactic position is that in all the aforementioned contexts, this hieroglyph is preceded by a complete sentence and connects the first clause with the second clause without the insertion of dates or distance numbers. For instance, on the Early Classic jade celt, the date 8 Ajaw 13 Keh introduces the text and references the end of the 9th Bak'tun (Figure 2). In Tikal's Stela 31, it follows the famous passage about the arrival of West K'awiil and Sihyaj K'ahk' in the context of the Teotihuacan entrada (Figure 3). On Tikal's Stela 40, the ya-hi-358 or ya-hi-358-ya hieroglyphic collocation and the new sentence it introduces are part of a longer sequence, though the poor state of preservation renders much of it barely legible (Figure 4). Tikal's Stela 12 provides information on its back side about the k'al tuun ceremony celebrated on the occasion of the 13 Tun ending on 9.4.13.0.0 (August 11, 527) by Ix Kaloomte' Ix Yok'in (?), the "Lady of Tikal" (Jones and Satterthwaite 1982: Figure 18) (Figure 5). The text on the left side continues with the hieroglyphic compound discussed, stating that Kaloomte' Bahlam, the 19th king of Tikal, erected the stela (Martin and Grube 2008: 38-39). On this monument, it is clear that the glyph block connects two consecutive but related events. Although the protagonists were different, both contributed to the celebration of the uxlajuun tuun-ending in 527 CE.

The lengthy inscription on Caracol's Stela 6 (Figure 6) describes the ascension to the throne of Yajawte’ K'inich II. The corresponding text begins with a reference to Yajawte’ K'inich's accession and connects it to the handover of the royal headband, ajaw huun, to his son. The accession of Yajawte’ K'inich is written as CHUM-la-ji-ya, with the -jiiy ending projecting the first verb into the background of the narrative. The focus is clearly on the new ya-AK’-wa verb. Here, the ya-hi-358 compound functions similarly to the particle i, which typically marks the posteriority of verbal expressions within a narrative sequence. Lastly, on Caracol's Altar 21, the hieroglyphic compound discussed transitions from one event—in this case, the "star war" against Tikal—to a subsequent event (Figure 7).

All these occurrences unequivocally indicate that the ya-hi-358 hieroglyph serves a syntactic function, connecting two sentences and leading from one event to the next. The text on Caracol Stela 6 clearly demonstrates that the preverbal ya-hi-358 hieroglyph implies a sequence from an earlier to a later event. Therefore, it likely functions as an adverb or particle with the meaning "and then" or "next." Additionally, the presence of the prefixed ya syllable indicates that the entire expression begins with ya. In the relevant languages, various particles could fulfill these conditions. The most plausible reading is likely ya' or ya’i, based on CHL ya’ “adv. allá“, ya’i „adv. allí, ahí” (Aulie and Aulie 1978: 141); Colonial CHN yai “part. Demonstrative: allí” (Smailus 1975: 178); CHN de ya’i “luego, después” (Keller and Luciano G. 1997: 294); CHR yayi “adv. and from there, next” (Hull 2016: 516); Proto-Cholan: *ya‘(i) “allí, allá” (Kaufman and Norman 1984: 139).

However, this interpretation of the hieroglyph ya-hi-358 remains incomplete until a convincing reading for the sign 358 itself is found, one that can explain the characteristic representation of kneeling legs. The solution may lie in the fact that in all relevant languages, the word for "leg," "muscle," and "thigh" is a'. For example, Proto-Cholan *a‘ means “thigh, leg,” derived from Proto-Maya *aa’ (Kaufman and Norman 1984: 115); in CHL, ya‘ signifies “leg, thigh” (Aulie and Aulie 1978: 141)[2]; in CHR, a’ means “thigh, upper leg” (Wisdom 1940); in TZO, ‘o‘il translates to “flank, leg of animal, thigh” (Laughlin 1988: 150); and in TZE, ya’ means “hip, his/her hip” (Slocum and Gerdel 1971: 206). Related nouns for "muscle, leg, thigh" are also found in K'iche', Kaqchikel, Tz'utujil, and Q'eqchi'[3] (Kaufman 2003: 345). This establishes a link between the reading and the graphic icon, which greatly enhances the plausibility of the interpretation.

|

|

|

Figure 8. Two occurrences of the sign T358 outside of the adverbial expression: a) AJ-K’IN-A’-a on the so called “Brussels Stela” from Sak Tz'i' (Drawing by Nikolai Grube after Mayer 1978: Cat. No. 2); b) ch’a-hi-A’ or ch’a-A’-hi on El Palmar Stela, 45 (Drawing by Nikolai Grube after Mayer 1991: Plate 35). CC-BY 4.0 Nikolai Grube. |

|

The two occurrences of the sign T358 outside its adverbial context can plausibly be explained by interpreting the sign as A’. On the Sak Tz'i stela from Brussels (Mayer 1978: Cat. No. 2) (Figure 8a), the sign appears within a hieroglyph that is part of a sequence of personal names and titles of individuals assembled before the ruler of Sak Tz'i. This hieroglyphic block can be read as aj-K'IN-a'-a, meaning "person from K'ina'/Piedras Negras". In this context, the final a-sign seems to function as a phonetic complement that reinforces the vowel. Another instance of T358 is found on El Palmar Stela 45 (Mayer 1991: Plate 35) (Figure 8b). Here, the sign appears in the combination ch'a-hi-358, which could possibly represent the word ch'aaha' or ch'aa'hi, whose meaning is unknown, or it may denote a toponym, Ch’aaha’. Unfortunately, the context in which this hieroglyph appears remains rather opaque.

The sign T358, therefore, almost certainly represents the logogram A' meaning “leg, muscle, thigh”. However, in most occurrences, the sign is clearly not used logographically, but for its phonetic value. This raises the question of why this sign does not substitute with others from the group of vowel a signs. The most plausible explanation is that there were specific semantic restrictions governing the use of otherwise homophonic signs. Additionally, the sign T358 differs from other signs representing the vowel a due to the presence of the final glottal stop. This distinction was likely important for the phonemically accurate rendering of the adverb "and then, finally" as yaa'hi or yaa'i.

References

Aulie, H. Wilbur, and Evelyn W. Aulie

1978 Diccionario ch’ol-español, español-ch’ol. Serie de Vocabularios y Diccionarios Indígenas, Mariano Silva y Aceves 21. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, México, D.F.

Beliaev, Dmitri, and Stephen D. Houston

2020 A Sacrificial Sign in Maya Writing. Maya Decipherment. https://mayadecipherment.com/2020/06/20/a-sacrificial-sign-in-maya-writing/

Berjonneau, Gerald, Emile Deletaille, and Jean-Louis Sonnery

1985 Rediscovered Masterpieces of Mesoamerica: Mexico–Guatemala–Honduras. Editions Arts, Boulogne.

Chase, Arlen F.

1991 Cycles of Time: Caracol in the Maya Realm. In Sixth Palenque Round Table, 1986, Palenque Round Table Series, vol. 8. edited by Virginia M. Fields, and Merle Greene Robertson, 33-42. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Fahsen, Federico

1987 A Glyph for Self-Sacrifice in Several Maya Inscriptions. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 11. Center for Maya Research, Washington, D.C.

Fahsen, Federico, and Linda Schele

1991 A Reading for the Penis-Perforation Glyph. Texas Notes on Precolumbian Art, Writing and Culture 8. Center of the History and Art of Ancient American Cultures, Art Department, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Grube, Nikolai

1994 Epigraphic Research at Caracol, Belize. In Studies in the Archaeology of Caracol, Belize, edited by Diane Z. Chase and Arlen F. Chase, 83–122. Monograph 7. Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, San Francisco, CA.

1999 Una nueva interpretación de la dinastía de Tikal. Paper presented during 4o Congreso Internacional de Mayistas. Antigua Guatemala.

2020 A Logogram for YAH „Wound”. Research Note 17. Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya, Bonn. https://doi.org/10.20376/idiom-23665556.20.rn017.en

Hull, Kerry

2016 A Dictionary of Ch’orti’ Mayan-Spanish-English. The University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Jones, Christopher, and Linton Satterthwaite

1982 The Monuments and Inscriptions of Tikal: The Carved Monuments. Tikal Report 33, Part A. The University Museum, Pennsylvania, PA.

Kaufman, Terrence S.

2003 A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Kaufman, Terrence S., and William M. Norman

1984 An Outline of Proto-Cholan Phonology, Morphology, and Vocabulary. In Phoneticism in Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing, edited by John J. Justeson and Lyle Campbell, 77-166. Publication 9. Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, State University of New York, Albany, NY.

Keller, Kathryn, and Plácido Luciano G.

1997 Diccionario chontal de Tabasco (mayense). Serie de Vocabularios y Diccionarios Indígenas “Mariano Silva y Aceves” 36. Summer Institute of Linguistics, Tucson, AZ.

Laughlin, Robert M.

1988 The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of Santo Domingo Zinacantán. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology 31. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Looper, Matthew G., and Martha J. Macri

1991-2024 Maya Hieroglyphic Database. Department of Art and Art History, California State University, Chico, CA. www.mayadatabase.org

Macri, Martha J., and Matthew G. Looper

2003 The New Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs, Volume 1: The Classic Period inscriptions. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube

2008 Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. Thames and Hudson, London and New York.

Mayer, Karl Herbert

1978 Maya Monuments: Sculptures of Unknown Provenance in Europe. Acoma Books, Ramona, CA.

1991 Maya Monuments: Sculptures of Unknown Provenance: Supplement 3. Verlag von Flemming, Berlin.

Moholy-Nagy, Hattula

2008 The Artifacts of Tikal: Ornamental and Ceremonial Artifacts and Unworked Material. Tikal Report 27, Part A. University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, PA.

Prager, Christian, and Sven Gronemeyer

2018 Neue Ergebnisse in der Erforschung der Graphemik und Graphetik des Klassischen Maya. In: Ägyptologische “Binsen”-Weisheiten III: Formen und Funktionen von Zeichenliste und Paläographie. [Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Abhandlungen der Geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse 15], edited by Svenja A. Gülden, Kyra V. J. van der Moezel, and Ursula Verhoeven-van Elsbergen, 135–181. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart.

Schele, Linda, and Nikolai Grube

1994 Notebook for the XVIIIth Maya Hieroglyphic Workshop at Texas, March 13-14, 1994: Tlaloc-Venus Warfare: The Peten Wars. Department of Art and Art History, College of Fine Arts, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Slocum, Marianna C., and Florencia L. Gerdel

1971 Vocabulario Tzeltal de Bachajon. Serie de Vocabularies y Diccionarios Indígenas “Mariano Silva y Aceves” 13. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, México, D.F.

Smailus, Ortwin

1975 El Maya-Chontal de Acalan. Análisis lingüístico de un documento de los años 1610-12. Cuaderno 9. Centro de Estudios Mayas, Universidad Autónoma de México, México, D.F.

Stuart, David

2020 Yesterday’s Moon: A Decipherment of the Classic Mayan Adverb ak’biiy. Maya Decipherment. https://mayadecipherment.com/2020/08/01/yesterdays-moon-a-decipherment-of-the-classic-mayan-adverb-akbiiy/

Thompson, John Eric S.

1962 A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK.

Valdés, Juan Antonio, Federico Fahsen, and Gaspar Muñoz Cosme

1987 Estela 40 de Tikal: Hallazgo y lectura. Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala, Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional, Guatemala.

Wirsing, Paul

1930 Wörterbuch Kekchi-Deutsch. Manuscript.

Wisdom, Charles

1950 Materials on the Chorti Language. Microfilm Collection of Manuscripts on Mesoamerican Cultural Anthropology 28. University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Footnotes

- As part of our work on a new catalog of Maya signs and their graphs, we are currently evaluating and revising Thompson’s Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs (1962). We are critically scrutinizing his system with the help of his original grey cards and supplementing it with signs that were not included in Thompson’s original catalog. Despite its known shortcomings and incompleteness, his catalog is still regarded as the standard work for Maya epigraphers, which is why we adopt Thompson’s nomenclature while removing misclassifications and duplicates, merging graph variants under a common nomenclature, and adding new signs or allographs to the sign index in sequence, starting with the number 1500. Allographs are also further organized with the help of newly defined classification and systematization criteria, which we described in detail in Prager and Gronemeyer (2018).

- Ch’ol ya‘ seems to include a frozen prevocalic ergative pronoun (y-) in front of a’ “leg” which indicates the concept of the inalienability of body parts. It is possible that in some contexts, the ergative pronoun was understood to be part of the logogram. This could eventually account for the absence of the ya syllable on Caracol Altar 21.

- For example, in Paul Wirsing‘s 1930 Q’eqchi’ dictionary, the entry is a “Schenkel, Bein”.