und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

From Fragments to Clarity: Reconstructing The Hieroglyphic Narrative of Lintel 34 from Yaxchilan (Chiapas, Mexico)

Research Note 30

September 25, 2024

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.24.rn030.en

Christian M. Prager (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Antje Grothe (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Introduction

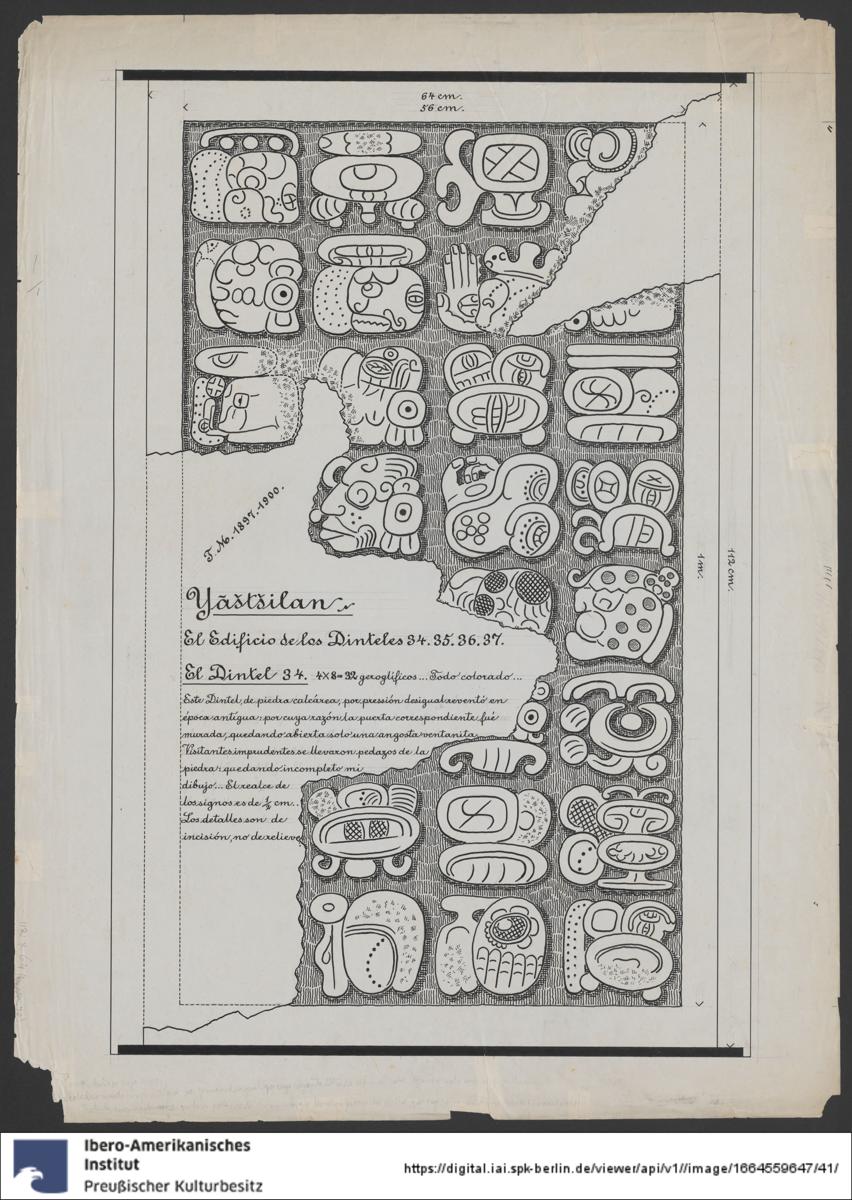

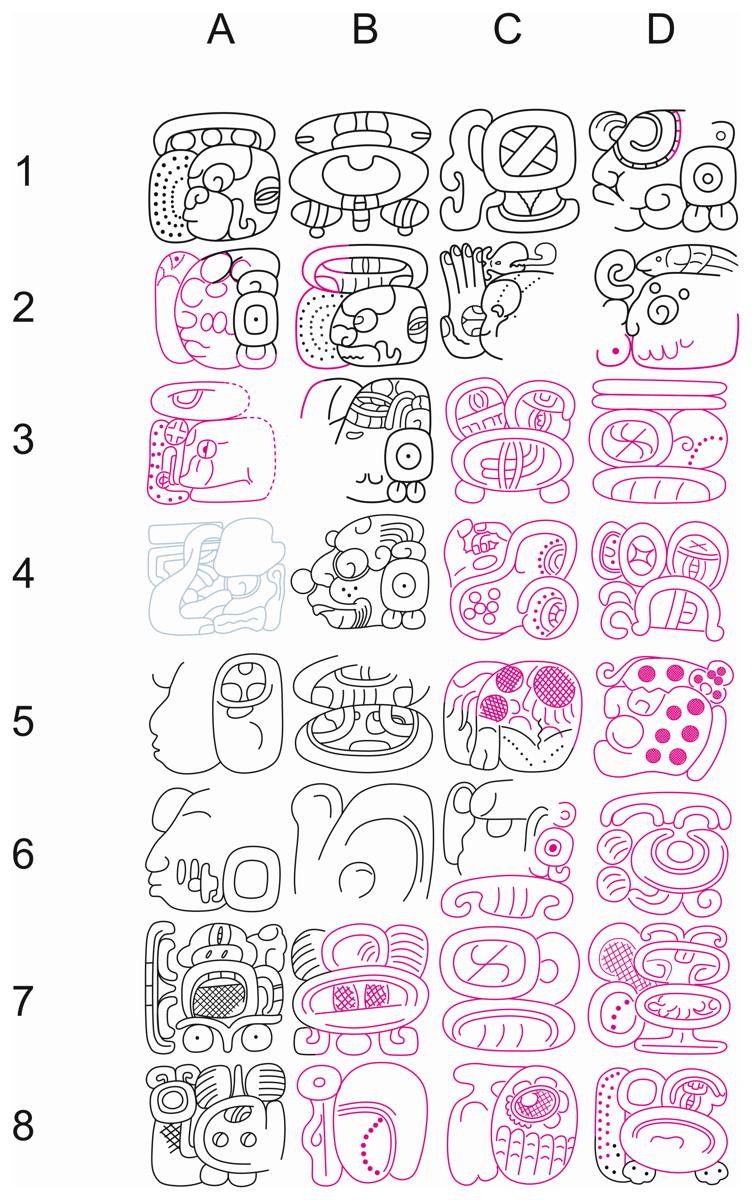

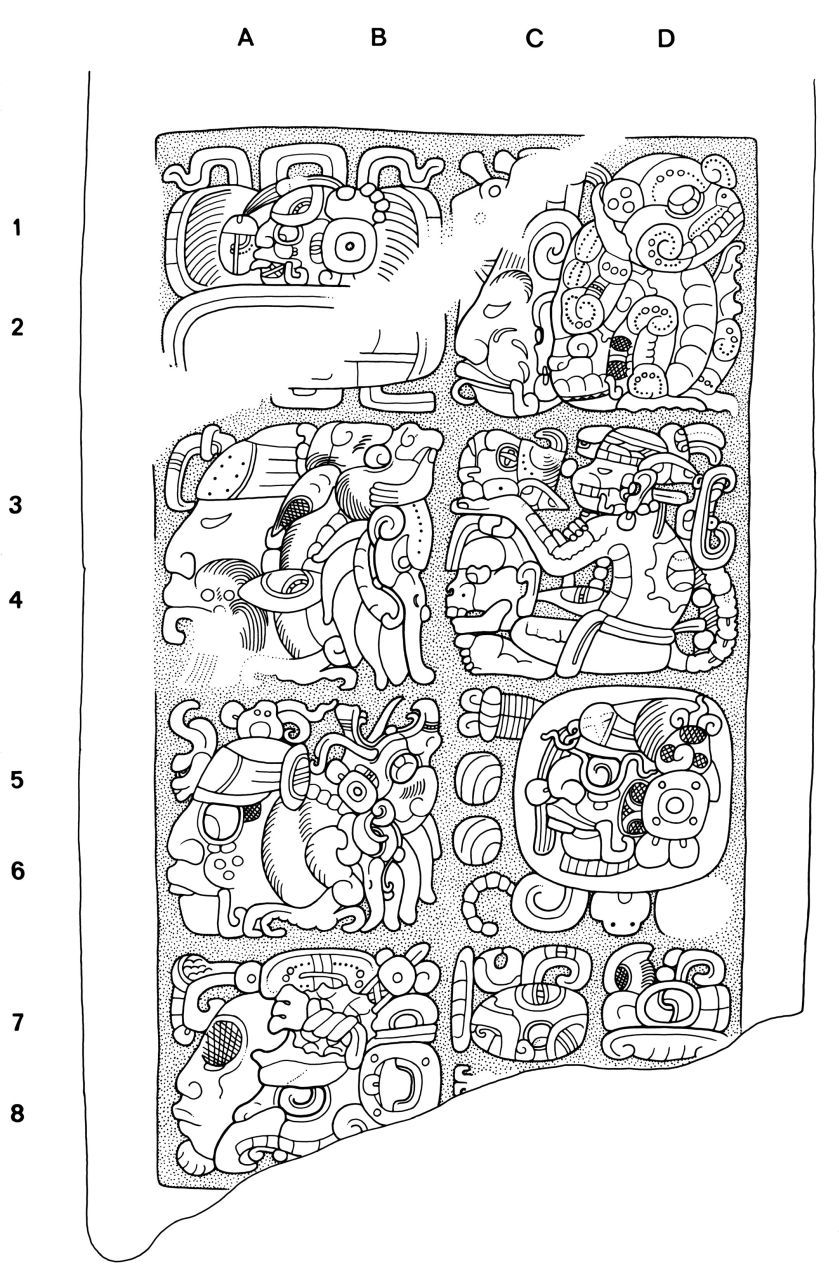

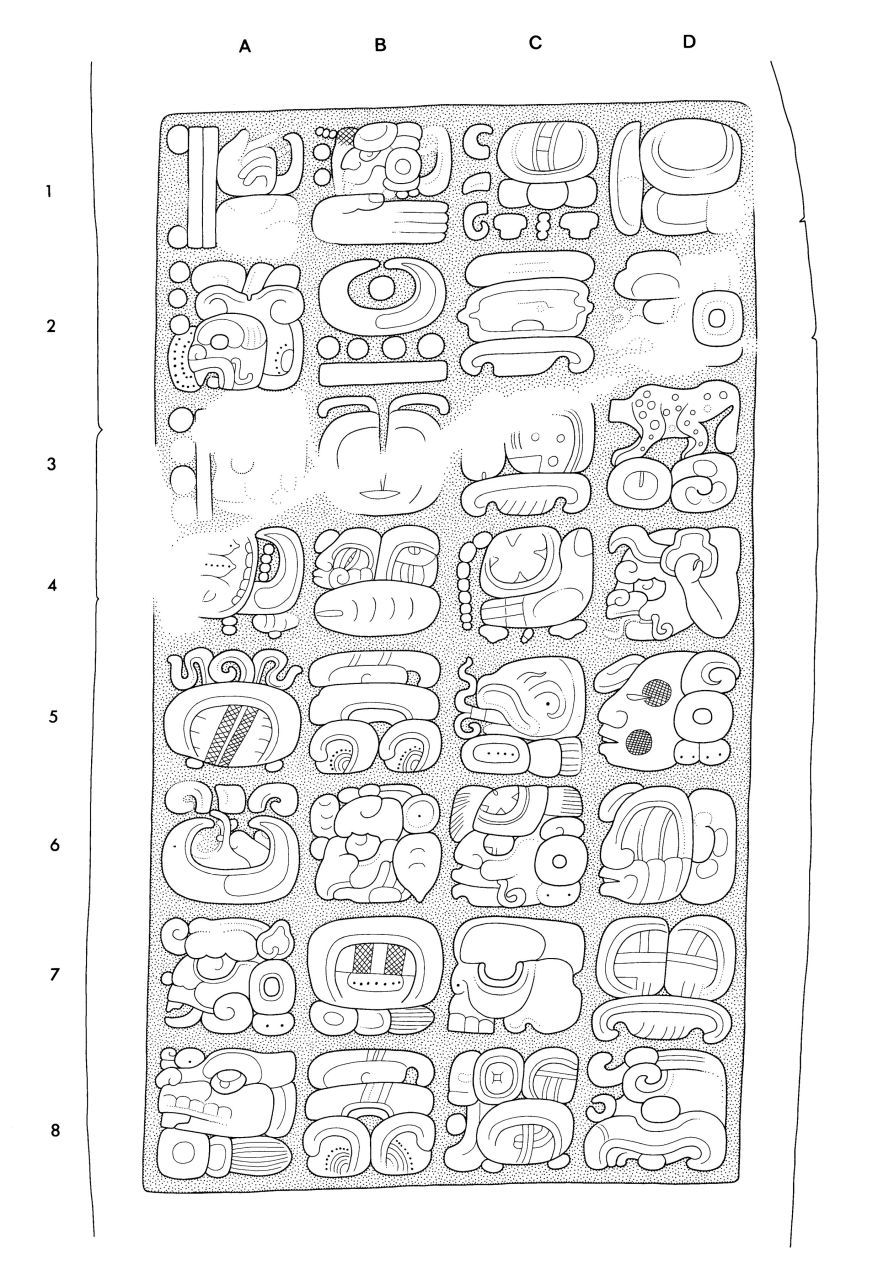

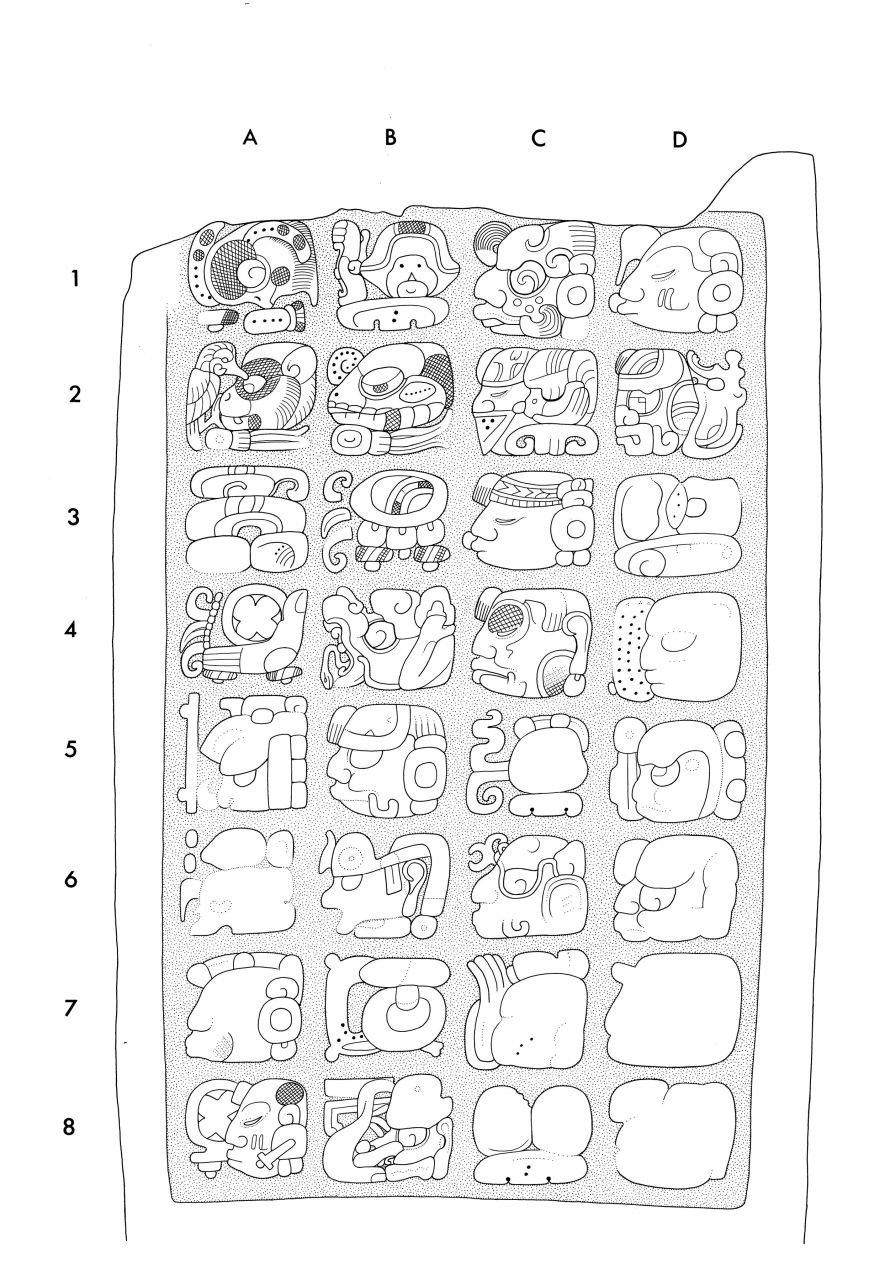

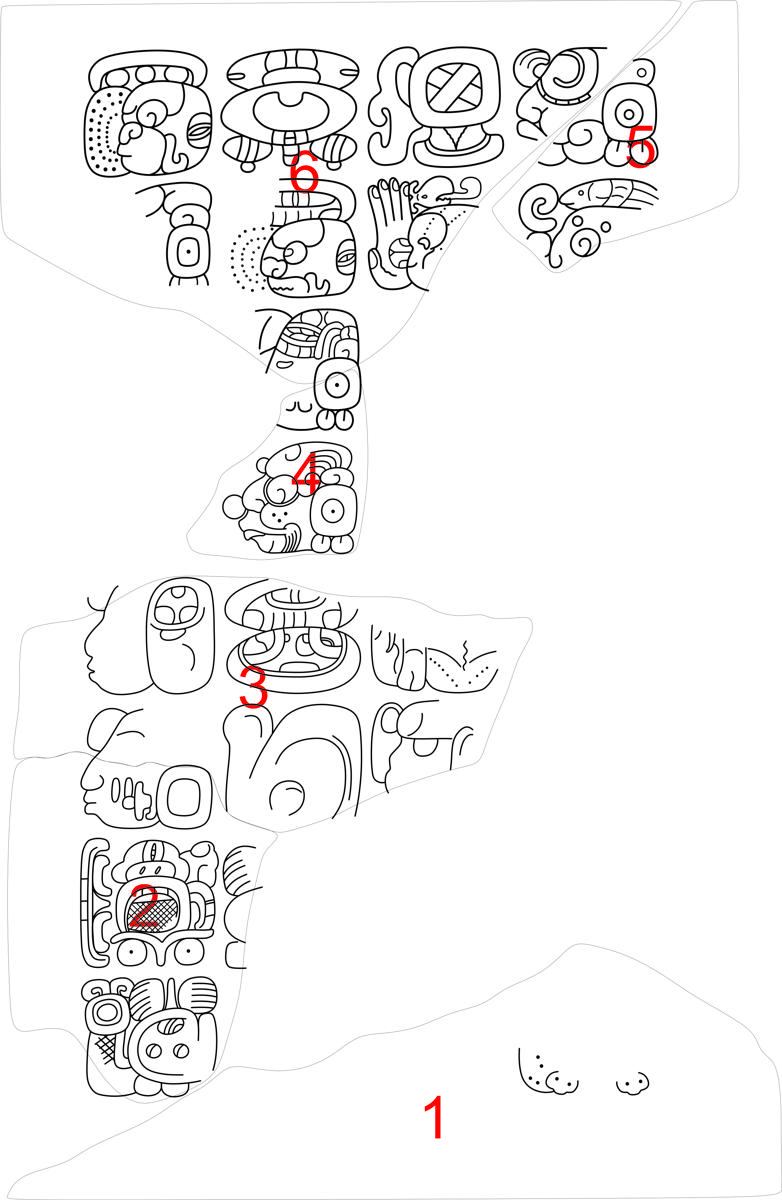

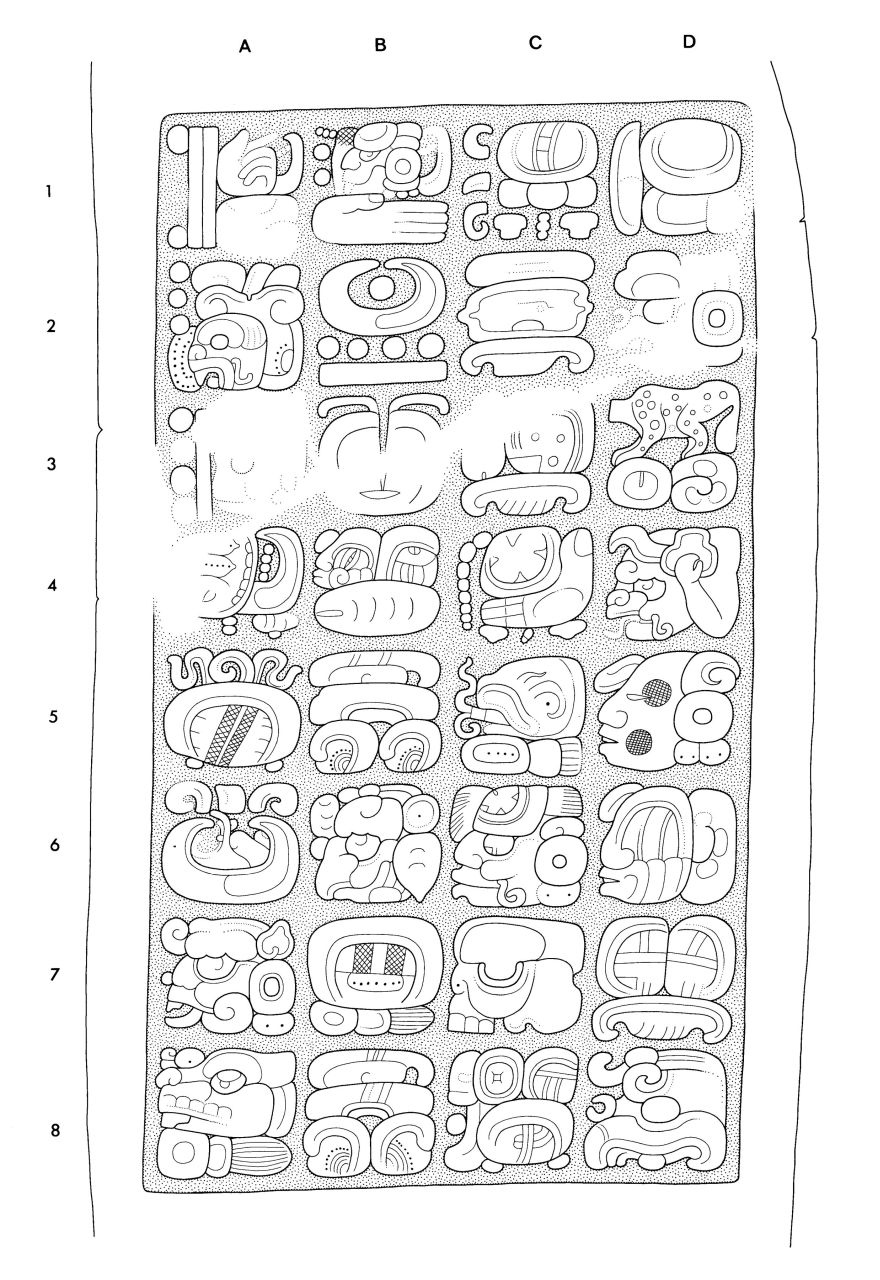

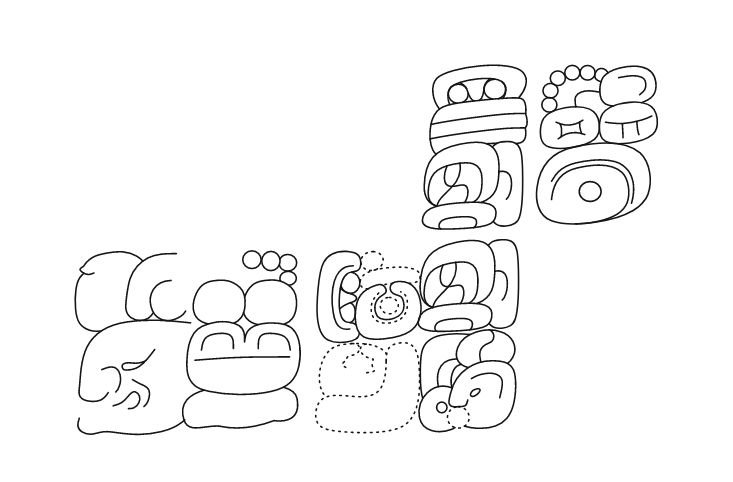

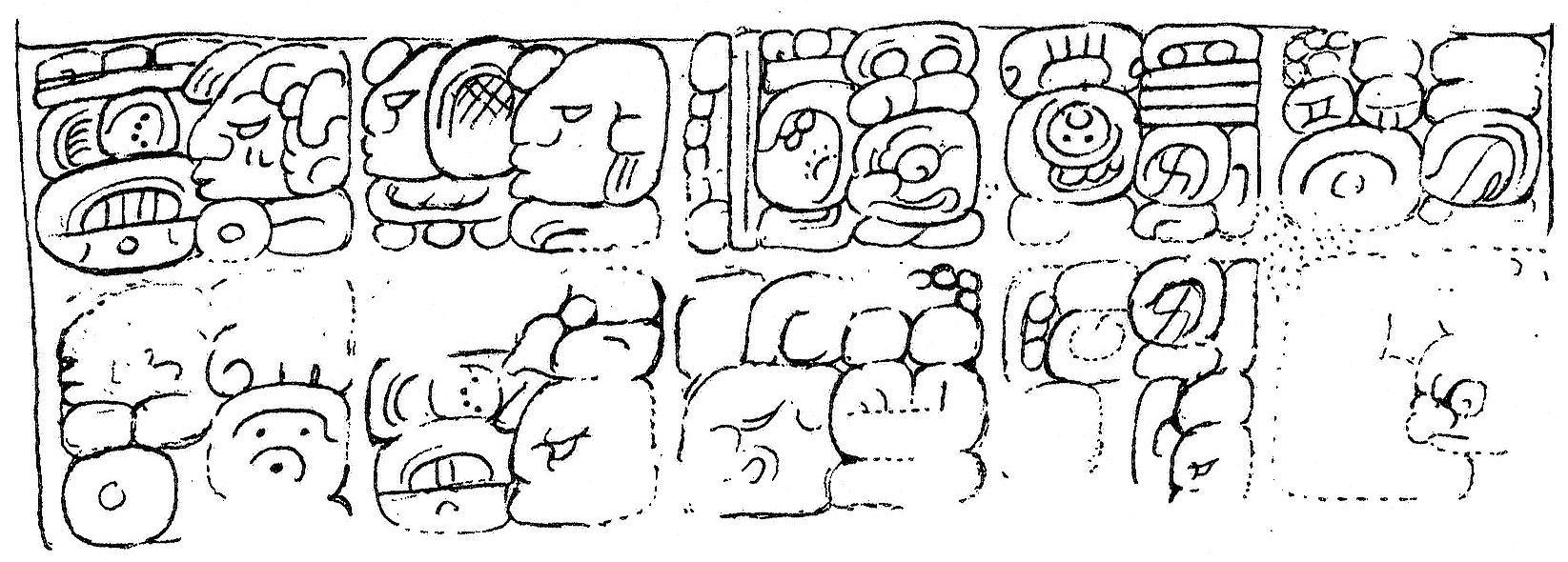

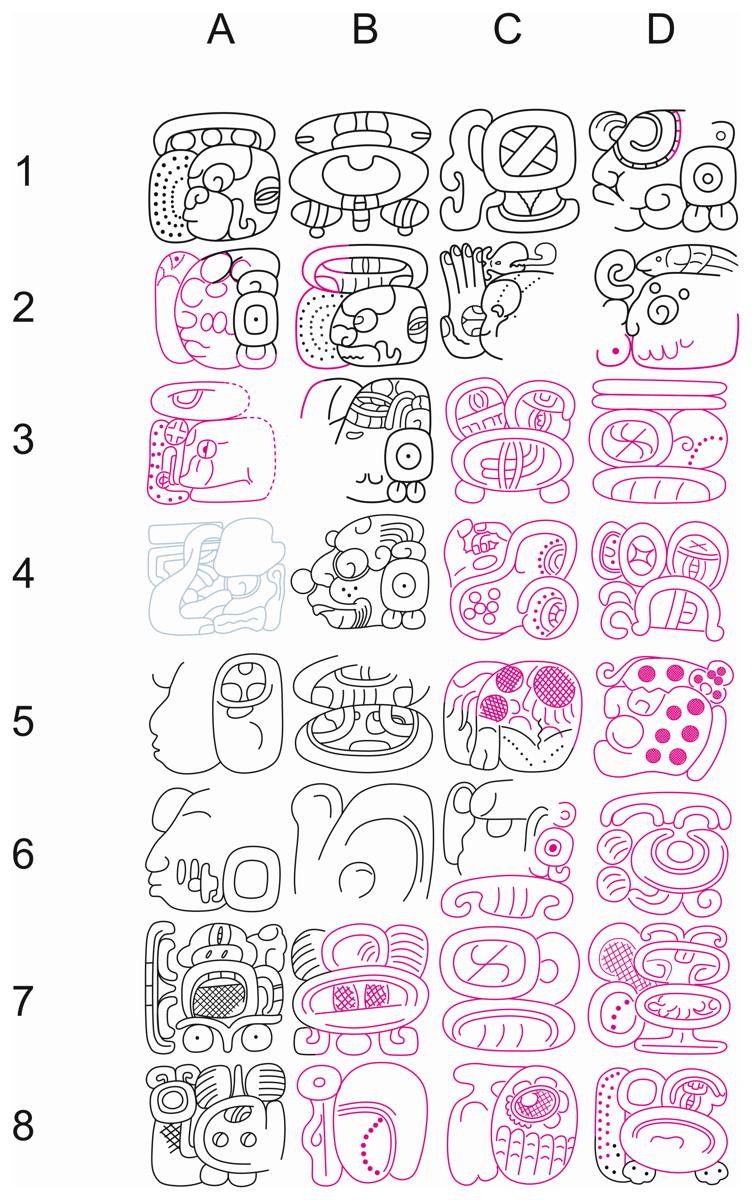

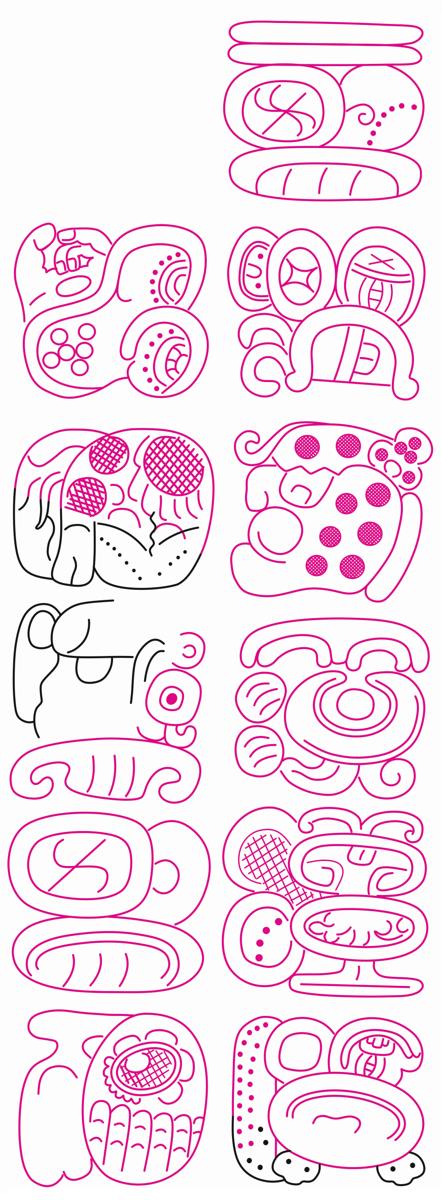

During the investigation for the Maya Image Archive of the "Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Maya" project[1], Antje Grothe identified a previously unknown drawing by the German-Austrian architect and explorer Teobert Maler (1842-1917) (cf. Maler 1997). This artwork, dated around 1900, was recently published within Maler's digital repository at the Ibero-American Institute in Berlin. The pencil-and-ink rendering illustrates the inscription on Lintel 34 from the archaeological site of Yaxchilan (Chiapas, Mexico) (Figure 1). This inscription originally comprised 32 hieroglyphic blocks, many of which have been lost over time (Morley 1937:II:376; Graham 1979:3:77; Tate 1992:169). Notes written on the drawing, along with Maler's German comments in his book manuscript (Maler 1895:fols. 129-130, 206) as well as his published descriptions of Lintel 34 (Maler 1903:133, 196, pl. 39), suggest that the limestone lintel was already fragmented and incomplete when Maler first discovered it between 1897 and 1900. However, the newly identified drawing reveals the lintel in a surprisingly intact condition upon its discovery between 1897 and 1900. Maler's drawing holds profound significance, as it introduces previously unknown portions of text to the six existing and published fragments of Lintel 34 (Morley 1937:pl. 112e; Graham 1979:77; Graham 1982:140). The previously known fragments include only fifteen legible hieroglyphic blocks and five partially identifiable ones, resulting in a rather limited understanding of the inscription until now (Mathews 1988:70, 92, 118, 129; Tate 1992:169, 284). However, the discovery of Maler's remarkable sketch, when combined with the known fragments and in comparison with the inscription on Yaxchilan Lintel 22, now enables the reconstruction of all hieroglyphic blocks (Figure 2). This breakthrough facilitates a fresh epigraphic analysis and fosters a renewed discussion of the monument's revealed narrative (see Appendix 1 for a transliteration of the monument's text).

|

|

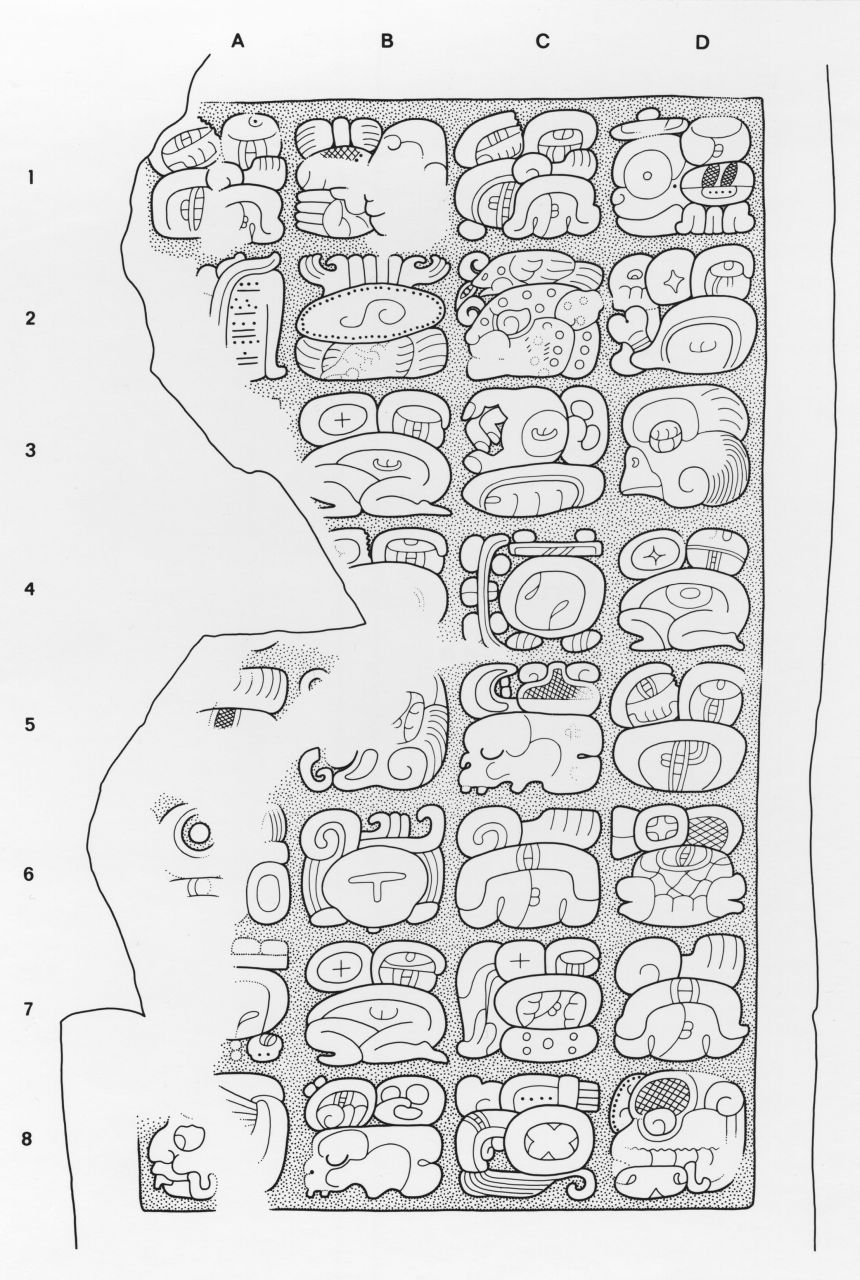

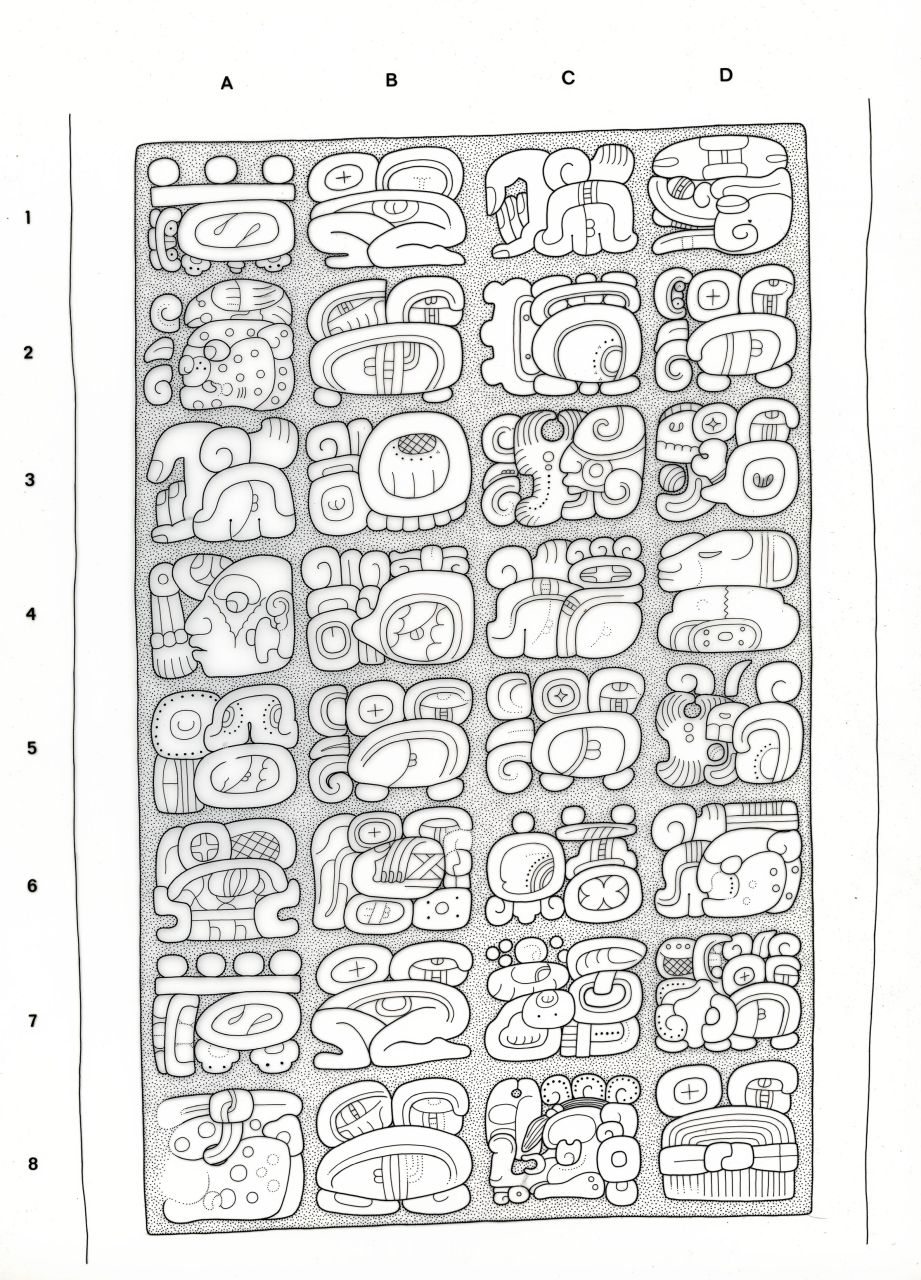

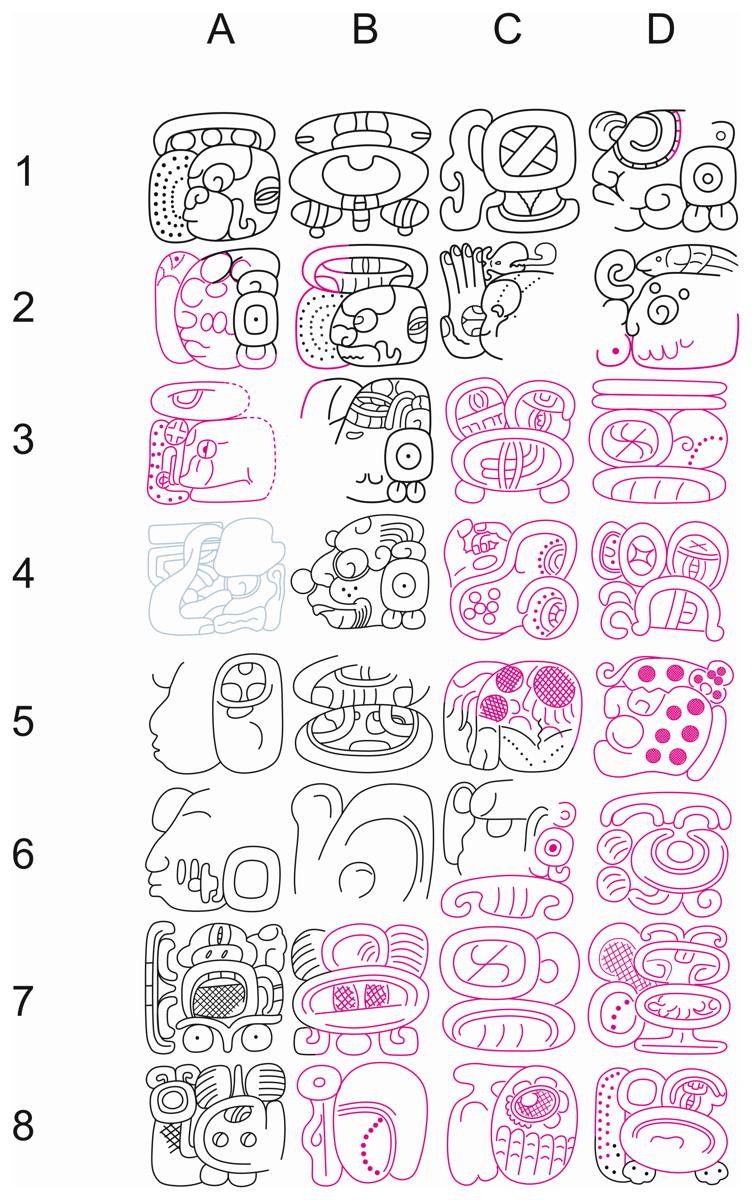

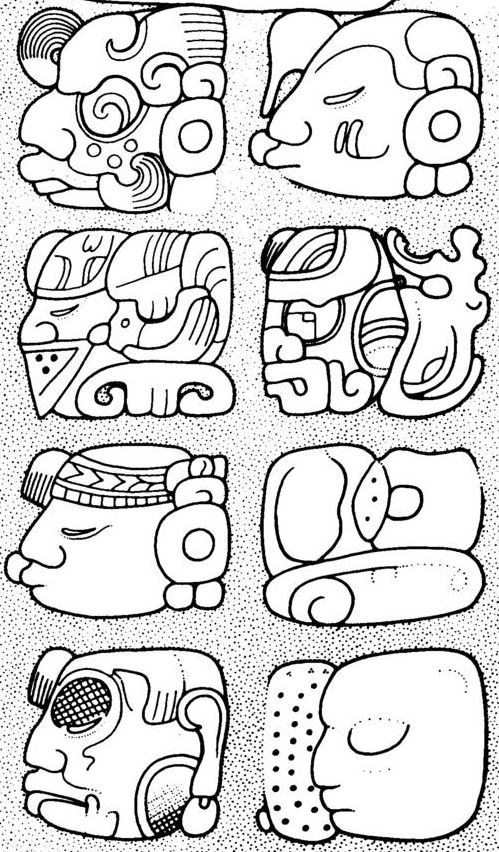

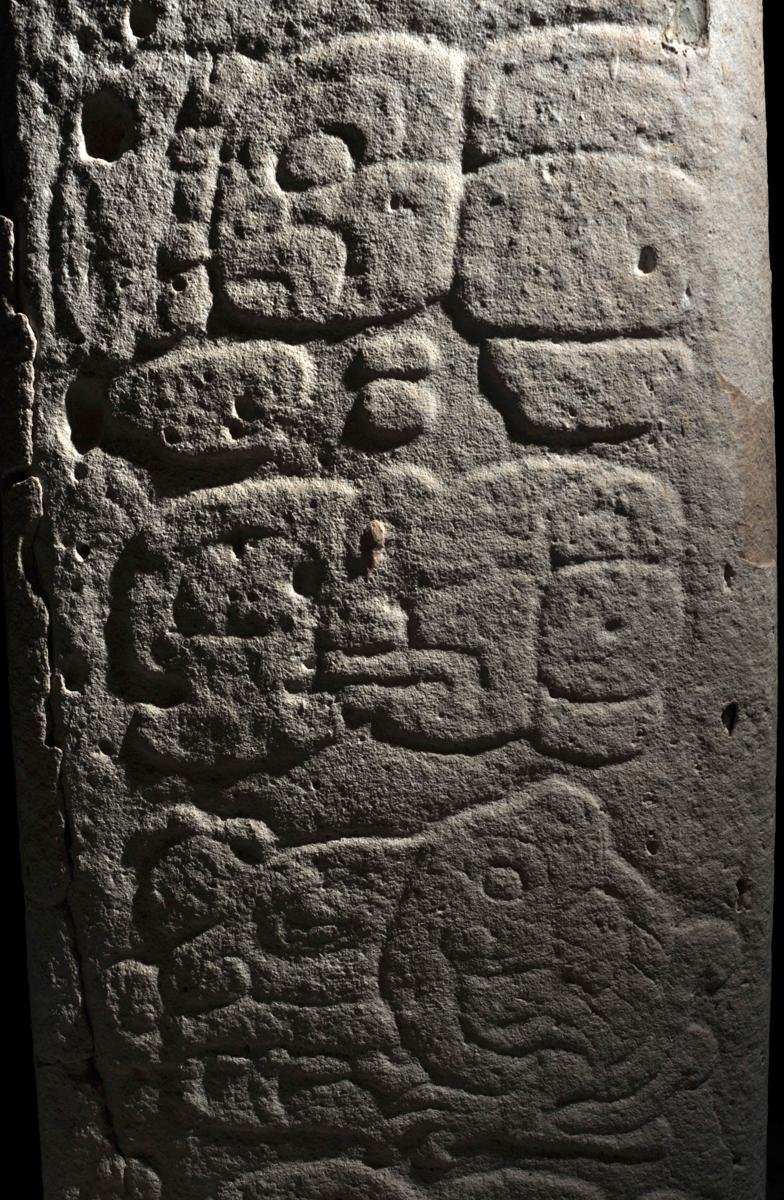

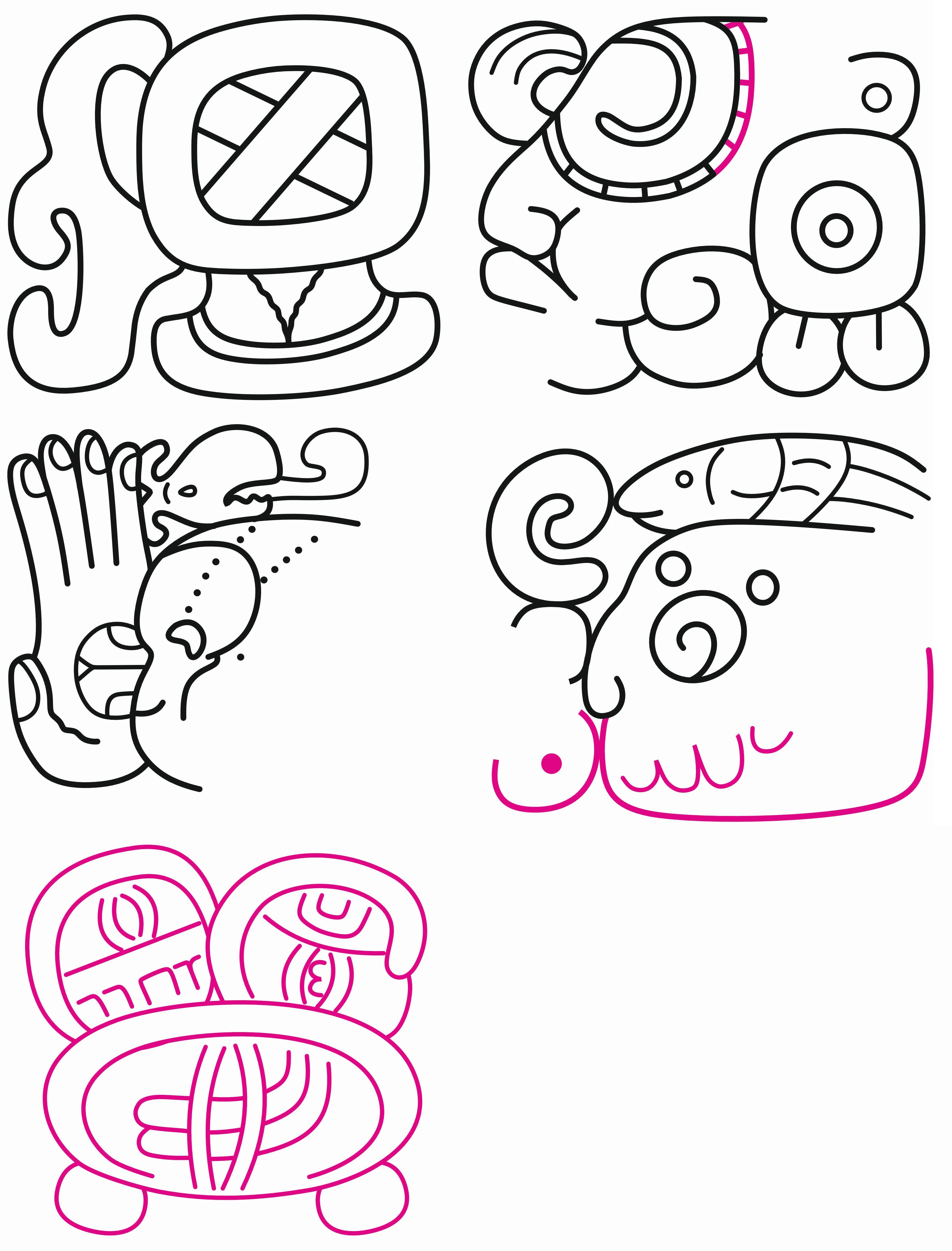

| Figure 1. Teobert Maler's drawing of Yaxchilan, Lintel 34 (created between 1897 and 1900). Image cited from Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut Berlin, Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, CC-BY-NC 4.0.[2] | Figure 2. A composite drawing of Yaxchilan, Lintel 34, by Christian Prager, combining Ian Graham's drawings (1979 and 1982) with Teobert Maler's original rendering (in red). Glyph block A4 is drawn by Prager after the text on Yaxchilan, Lintel 22. CC-BY 4.0. |

Context

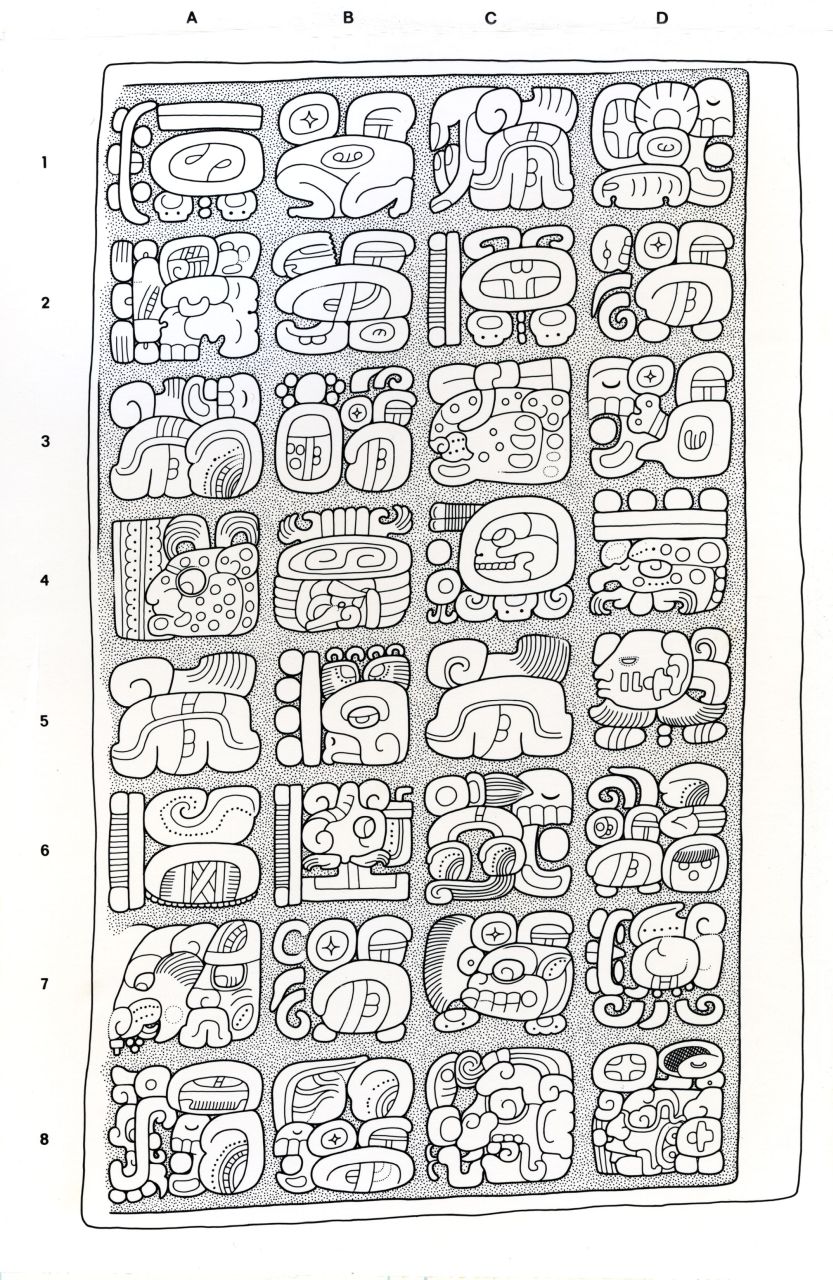

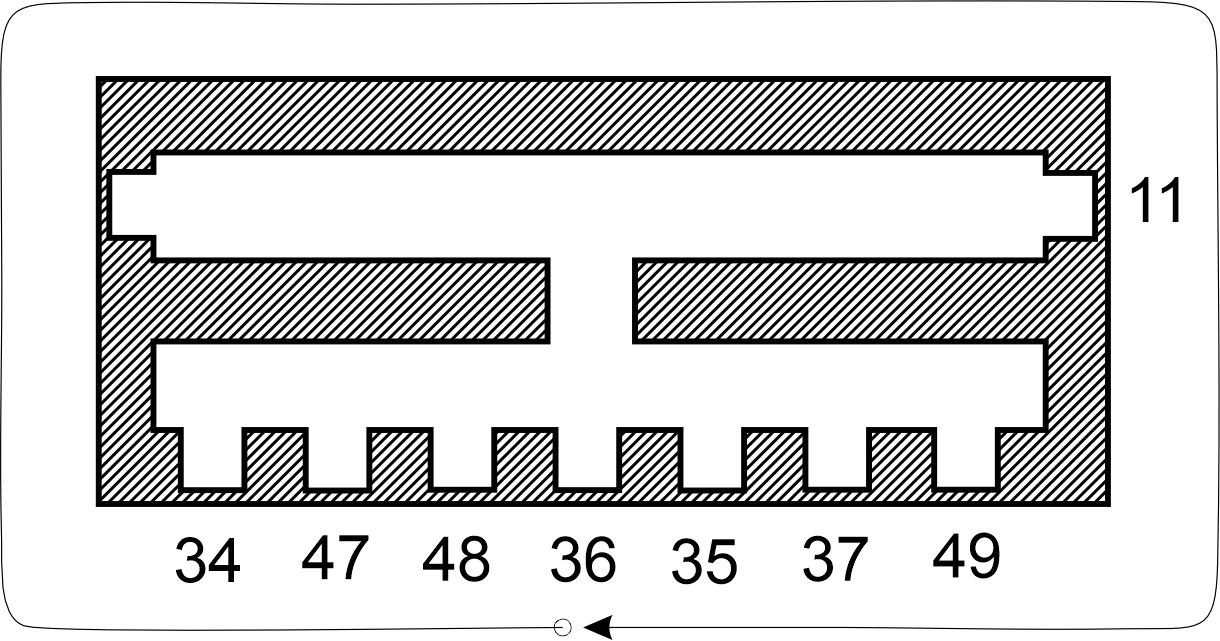

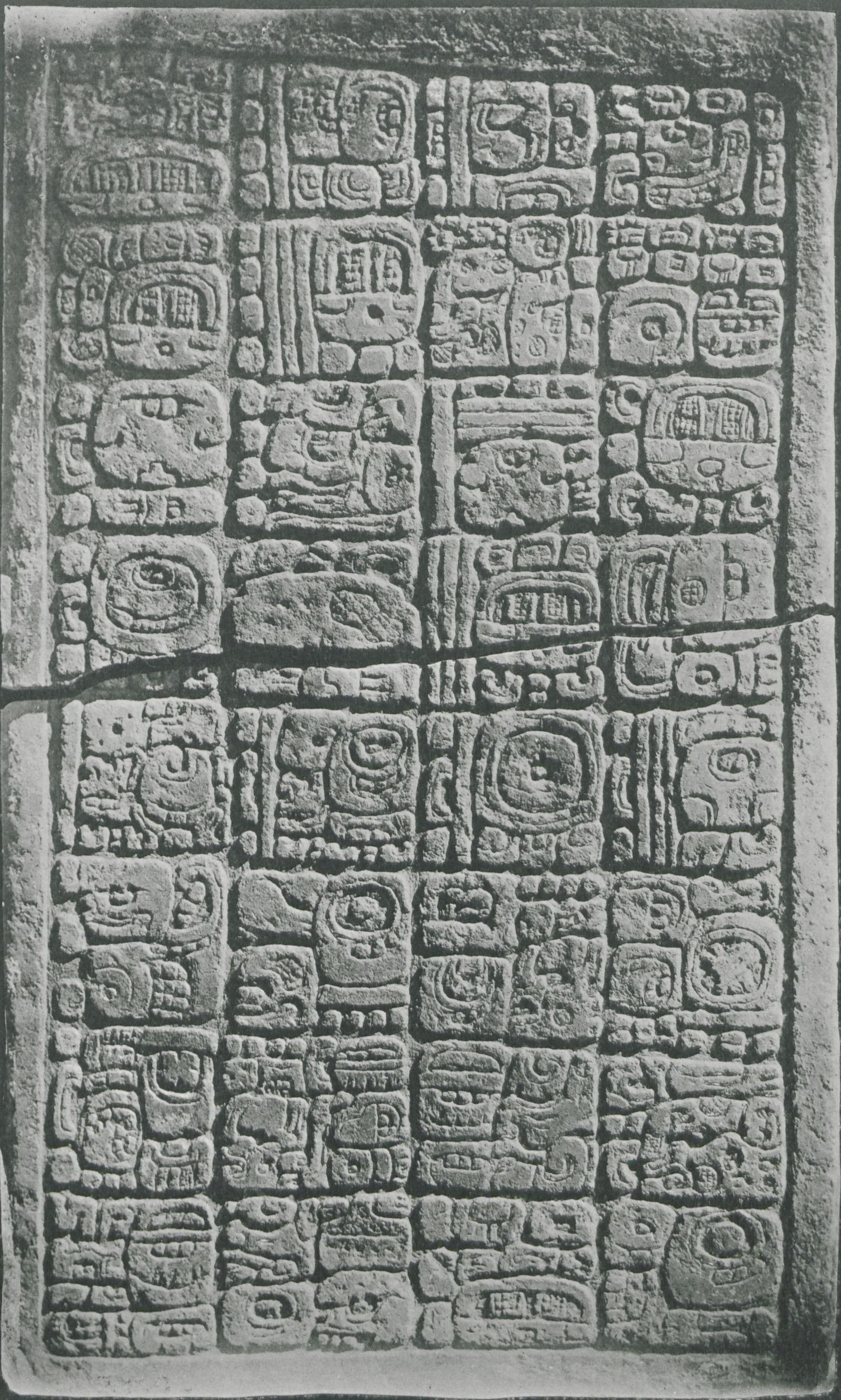

Lintel 34 is part of a set of eight lintels, seven of which date from the late Middle Classic period, or the 6th century, and were reassembled within the Late Classic Structure 12 during the 7th or 8th century[3] (Tate 1992:169–170). Lintels 34, 47, 48, 35, 37, 49, and 11 (previously designated Lintel 60)[4] are adorned exclusively with inscriptions, while the eighth, central Lintel 36, heavily eroded, also displays a standing figure and traces of indecipherable text (Morley 1937:V: Plate 113a), likely created and added during the construction of Structure 12 in either the 7th or 8th century[5] (Figure 3). These monuments, seven of them originally commissioned during the reign of Ruler 10 or K'inich Tatbu Joloom II[6] (Mathews 1988:68ff.; Tate 1992:169–170; Martin and Grube 2008:120), adorned the narrow entrances of Structure 12, which was unearthed in 1882 by Alfred P. Maudslay and later categorized by Linton Satterthwaite as belonging to the Late Classic period based on its architectural attributes (Morley 1937:II: 366; García Moll 2003:337) (Figure 3). A widespread consensus now exists that the lintels, originally dating to the 6th century were relocated from their unknown original locations in the 7th or 8th century during the reign of Bird Jaguar III (García Moll 2003:337) or Bird Jaguar IV[7] (Tate 1992:170; O’Neil 2011:245), depending on the dating of Structure 12. These lintels were subsequently reassembled into a new configuration within the newly constructed Structure 12. That building is located near the banks of the Usumacinta River, east of the northwestern ballcourt, or Structure 14. It consists of two large chambers whose connecting doorway was sealed in antiquity and reopened during the archaeological investigations. On the south-western façade of the building seven evenly spaced entrances were decorated with lintels numbered 34, 47, 48, 36, 35, 37 and 49, painted in red pigment and arranged from west to east. There were also two sealed entrances on the north-west and north-east sides of the building. In the latter, Roberto García Moll discovered a new lintel in situ in 1983, initially cataloged as number 60 (Tate 1992:170; García Moll 2003:53; Graham et al. 2022:198). Subsequently it was redesignated Lintel 11 by Ian Graham (Peter Mathews, personal communication, 2024)[8], now documented as such by the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Project (CMHI).[9]

|

|

|

|

| Yaxchilan, Lintel 36 | Yaxchilan, Lintel 48 | Yaxchilan, Lintel 47 | Yaxchilan, Lintel 34 |

|

|

|

|

| Yaxchilan, Lintel 11 | Yaxchilan, Lintel 49 | Yaxchilan, Lintel 37 | Yaxchilan, Lintel 35 |

|

|||

|

Figure 3. Floor plan and location of the eight sculpted lintels in Structure 12, with an arrow indicating the walking and reading sequence to interpret the texts as a coherent narrative (Composite drawing of Structure 12 by Christian Prager (2024) after Ian Graham (1977) and García Moll (2003); Yaxchilan, Lintel 36 © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.5.6.9; Yaxchilan, Lintel 48, underside, drawing by Ian Graham. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.6.21; Yaxchilan, Lintel 47. drawing by Ian Graham. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.6.20; Yaxchilan, Lintel 49, drawing by Ian Graham. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.6.22; Yaxchilan, Lintel 37, drawing by Ian Graham. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.6.8; Yaxchilan, Lintel 35, drawing by Ian Graham. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.6.7; Yaxchilan, Lintel 34: drawing by Christian Prager (2024) after Maler (1897-1900) and Graham (1977, 1982), CC-BY 4.0; Drawing of Lintel 11: drawing by David Stuart, in Mathews (1988:97). |

|||

Morley first asserted from the chronology that the lintels of Structure 12 had a fixed reading direction, with Lintel 36 centrally positioned for symmetrical and semiotic purposes (Morley 1937:II:367). This heavily eroded lintel, maybe produced in the 7th or 8th century as part of this construction program, was placed above the central entrance of Structure 12 (Figure 3). It depicts traces of a standing figure adorned in full regalia, potentially representing either the dynastic founder Yopaat Bahlam, KTJ-II (Taylor 1983:144), who commissioned this series of monuments, or a Late Classic king responsible for the construction of Structure 12, maybe Bird Jaguar III (according to the chronology by García Moll 2003) or Bird Jaguar IV (O’Neil 2011:259) (Figure 3). Lintel 36 and its visuals originally served as the semiotic focal point, marking both the beginning and endpoint of a historical narrative about the Middle Classic dynastic and military history of Yaxchilan, set within its architectural context. The visual and textual narrative scheme undoubtedly begins with Lintel 36 and chronologically progresses to the three west-facing monuments 48, 47, and 34, where, according to the inscriptions, KTJ-II was enthroned on 9.4.11.8.16. The narrative continues on Lintels 47 and 34, detailing family and dynastic origins, which can now be further contextualized through the newly discovered drawing by Maler, allowing for the reconstruction of the full text of Lintel 34 (Figure 2, Figure 3).

The inscription on Lintel 34, meticulously reconstituted from Teobert Maler's drawing (Figure 1 and 2), proclaims the origins of the local dynasty in Chihcha', or "Maguey-Place", a legendary cradle of influential Lowland Maya dynasties. It traces the lineage of KTJ-II, the commissioner of the Structure 12 memorial, to the so-called Kaaj(?) dynasty, spanning 22 generations to a dynastic founder whose name is also mentioned on Lintel 34. This text establishes a connection between KTJ-II, his biography mentioned on Lintels 48 and 47, and his predecessors, who are listed chronologically in the royal chronicle on Lintels 11, 49, 37, and 35. The census of the royal lineage commences on Lintel 11 in the northeast of the building and continues southwestward on Lintels 49, 37, and 35 (Proskouriakoff 1993:26; Taylor 1983:140ff.; Mathews 1980). This narrative progression spans from Yopaat Bahlam, the dynasty's founder, to its tenth ruler and commissioner, KTJ-II, on Lintel 35. These inscriptions not only record the names and titles of those rulers but also succinctly document their military successes, captured enemies, and their hegemonies (Mathews 1988). Thus, they magnify the historical-legendary narrative of the divine kingship in Yaxchilan and provide insights into a network of asymmetrical dependencies and political dominance from the commissioner's perspective. To comprehend the narrative in its correct chronological and semantic sequence, past visitors had to circulate around the building from east to west, beginning at the centrally positioned Lintel 36, thus traversing Yaxchilan's royal narrative from legendary to early and then later times (Proskouriakoff 1993:26; O’Neil 2011:256).

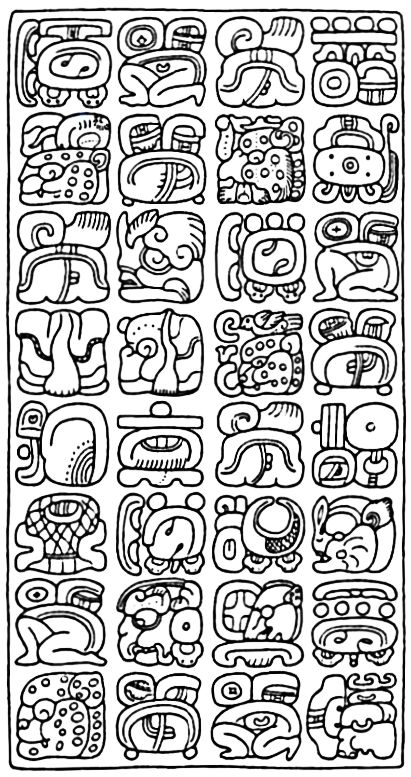

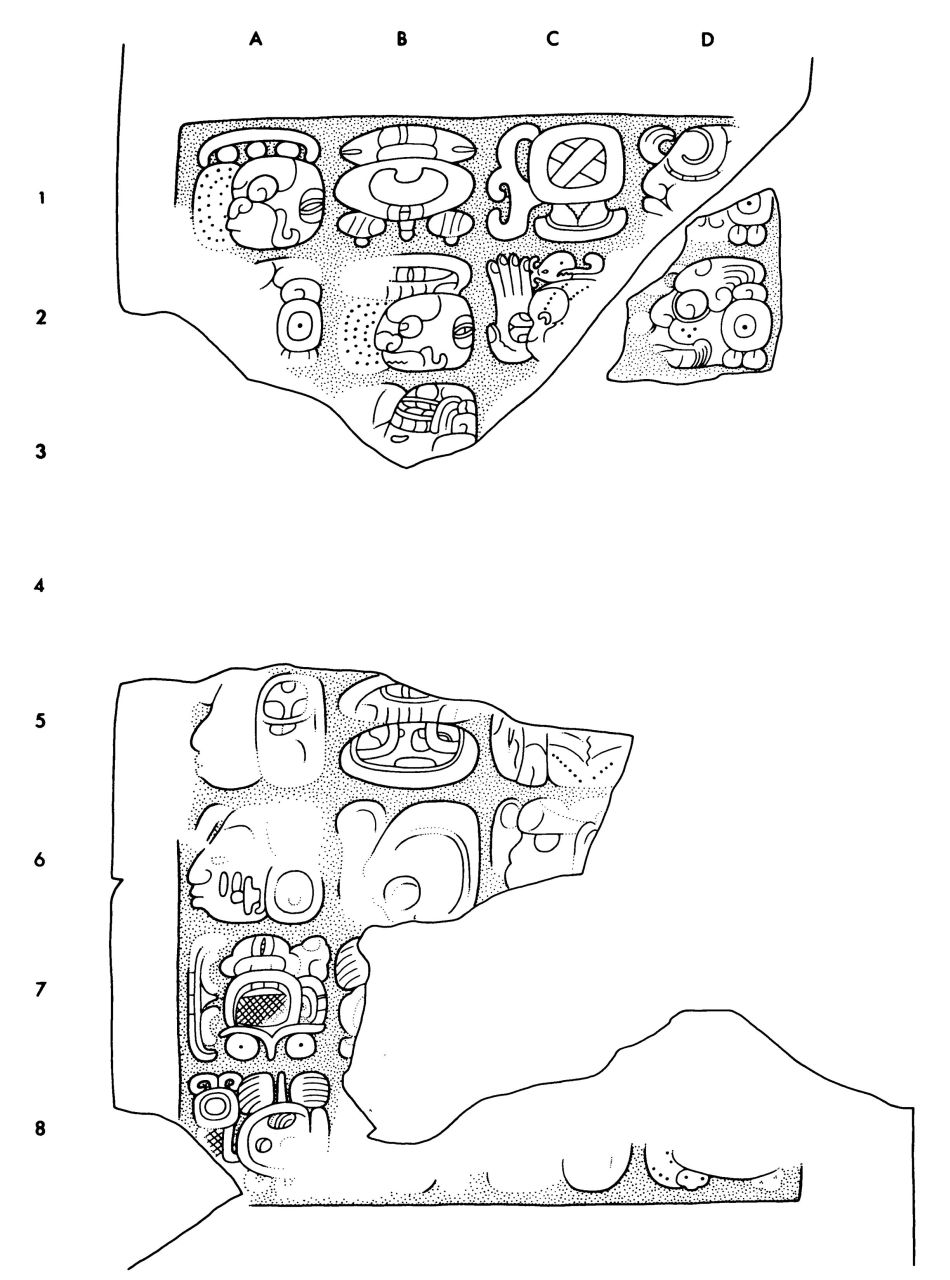

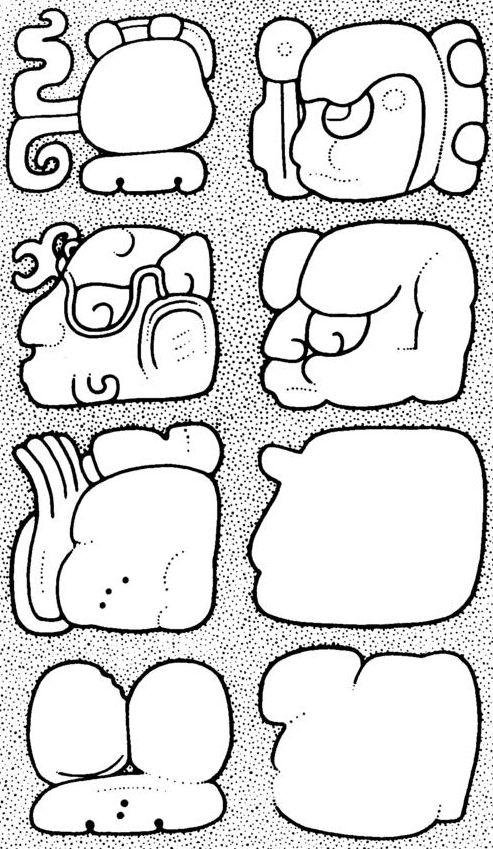

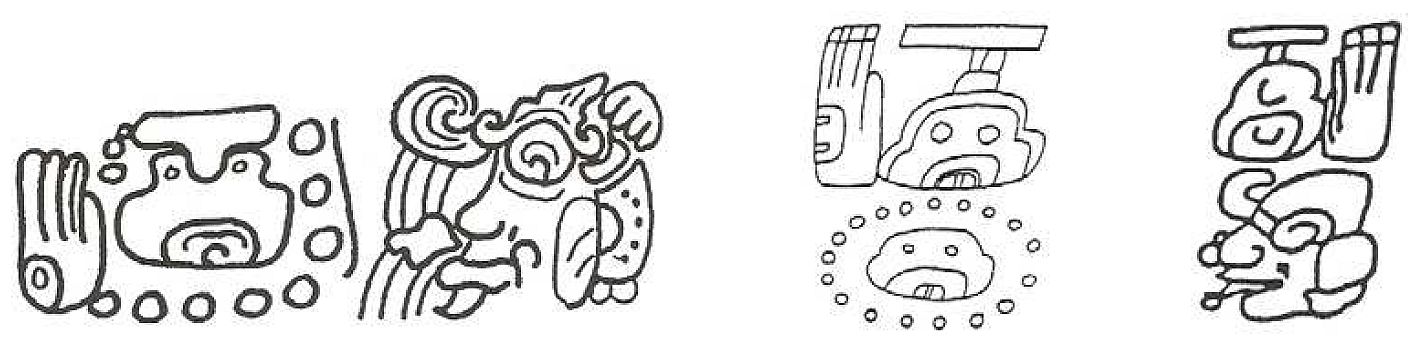

Regarding Middle Classic hieroglyphic texts from Yaxchilan, Lintels 20 and 22 warrant particular attention (Figure 4a and 4b). Both were discovered in the debris or in the immediate vicinity of Building 22 (Graham and von Euw 1977:47, 51) and have been dated to the reign of KTJ-II based on textual and palaeographic criteria (Mathews 1988:92–93; Martin and Grube 2008:120). Lintel 22, comprising 32 hieroglyphic blocks similar to the lintels from Structure 12, contains genealogical information about KTJ-II, akin to that recorded on Lintels 47 and 34. However, the chronology of these texts remains uncertain, as only the upper fragment of Lintel 20 survives, and the critical calendar inscription is missing. Building 22 was constructed following the interregnum during the reign of Bird Jaguar IV, around 9.16.1.0.0, and was inscribed with Early Classic hieroglyphic texts (Lintels 18, 19, 20, 22) from the era of his ancestor KTJ-II (Mathews 1988:334). To resolve the ten-year political crisis in Yaxchilan, during which only Yopaat Bahlam is mentioned as king of Yaxchilan in Piedras Negras, Bird Jaguar IV sought to reinforce and legitimize his rule by emphasizing the history of his ancestral lineage. A testament to this public historiography is Hieroglyphic Stairway 1, commissioned by Bird Jaguar IV, which, despite significant erosion, has references parralel to extensively references the lintels of KTJ-II (Mathews 1988; Nahm 1997; Nahm 2006). For understanding and historically contextualizing the inscription on Lintel 34, this group of texts will also be of significant importance.

|

|

|

Figure 4. Lintel 20 (left) and Lintel 22 (right) from Yaxchilan, Structure 22 (Yaxchilan, Lintel 20, underside fragment. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.5.5.19; Yaxchilan, Lintel 22, underside drawing by Eric von Euw. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.5.20). |

|

Having completed the extensive commentary on the architectural and historical setting of Lintel 34, the following section offers a description of the artifact and its scholarly exploration, with a particular focus on Teobert Maler's recently identified drawing. This will be followed by an epigraphic analysis of the reconstructed text, ultimately resulting in a new interpretation of the inscription and its historical implications.

Description and Research History

As mentioned above, Lintel 34 was situated above the southwesternmost, nearly completely sealed doorway of Structure 12 and was discovered in a fragmented state by Teobert Maler during his expeditions of 1897 or 1900[10] (Figure 3). The exact year of discovery remains undocumented; Morley, in his extensive study from 1937-1938 (Volume II, page 367), postulates the year 1900. Unfortunately, Maler's records do not provide more precise information on this matter. Rather than a photograph, Maler produced an exceptional drawing of the fragments remaining on-site, which, however, was not included in his seminal publications on Yaxchilan from 1901 and 1903. His annotations on the drawing suggest that it was created between 1897 and 1900, implying that the monument must have been discovered and documented by the 1900 field campaign at the latest. The recent digitization of his extensive estate by the Ibero-American Institute in Berlin has now made this drawing accessible, thus freely available for scholarly research.[11]

Maler's digitized drawing, along with available documentation of the physically remaining and previously known fragments, forms the foundation of the following discussion.[12] His hitherto unknown drawing captures the monument's remarkable state of preservation at the time of its discovery, originally fully painted in red (Maler 1895:fols. 129–130). It is evident from the drawing that by approximately 1900, a third of the left text and several areas in the right text were missing (Figure 1). According to Maler, these were removed by visitors to the site, who extracted parts of the fractured lintel by removing the underlying wall (Maler 1895:fol. 129). Specifically affected at the time of documentation were the hieroglyphic blocks A4, A5, B5, A6, B6, A7, A8, as well as parts of blocks D1, D2, C6, and C5. In the gap in his drawing, Maler noted in a brief text in Spanish the condition of the lintel and Structure 12.[13] At the top and right margin, he recorded the dimensions of the lintel and the sculpted area[14], which until now were either unknown or only estimated (Graham 1979:77). Above this note, there is a rotated text with Maler's monogram T.M., followed by the years 1897 and 1900, which possibly date the clearly discernible original pencil drawing, the subsequent inking, or perhaps the year of Lintel 34's discovery.

|

|

| Figure 5. The six surviving fragments of Yaxchilan, Lintel 34 (Left: Yaxchilan, Lintel 34: drawing by Christian Prager (2024) after Maler (1897-1900) and Graham (1977, 1982), CC-BY 4.0; Right: Yaxchilan, Lintel 34, drawing by Ian Graham. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.6.6). |

|

The six published and physically extant fragments were discovered during later excavations and explorations, with fragments 1, 4, and 6 already known to Maler and being included in his drawing (Figure 1 and 5). Prior to the current publication of his illustration, only fragments 1 through 6 of Lintel 34 were known (Graham 1979:77; Graham 1982:140). Five fragments (1, 2, 3, 5 and 6) were (re)discovered by Morley between April 15 and 17, 1931 (Morley 1937:II:376; Morley 1931:III-44 to III – 68)[15], while another fragment (number 4) was found around the turn of the century by Maler and delivered to the Peabody Museum[16], where it remains and has been identified by Graham (Graham and von Euw 1977:77; Graham 1982:140). Fragment 1, located at the lower end of the lintel, was still in situ in 1931. It was recovered by Morley and joined with fragments 2 and 3, which he had found inside the first chamber's floor (Morley 1937:II:376). The triangular fragment 6 at the upper end of the lintel was also found in situ by Morley but was not photographed until 1975 by Ian Graham, who incorporated it into his drawings of the lintel in the CMHI volumes of 1979 and 1982.[17] Morley (1937:II:376) also mentioned additional fragments that were not recovered, and their quantity remains unknown. One of these fragments (number 5), which is missing from Maler's drawing, was later found and identified by Graham in the bodega at Yaxchilan (Graham 1982:140). Fragment 6 was still in situ in 1975 and was photographed by Ian Graham during his documentation work for the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions project.

Five fragments, reportedly stored in the warehouse at Yaxchilan as of 1975 according to Graham, together with a sixth fragment held in the collections of the Peabody Museum, formed the basis for two drawings by Ian Graham. These drawings were published in 1979, with a revised version appearing in 1982, in two fascicles of the Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions (Graham 1979; 1982). These sources remain foundational for epigraphic studies and can now be significantly enhanced by Maler's drawing. Both sources—Maler's redrawing and the previously published fragments 1-6—complement each other remarkably well (Figure 2), effectively refuting Maler's claim that the fragments of Lintel 34 were stolen by visitors. A substantial portion of the fragments were found in situ or excavated from the rubble of Structure 12, allowing them to be reassembled into a comprehensive depiction. As a result of this discovery, 31 of the 32 hieroglyphic blocks are now legible, with only hieroglyphic block A4 remaining lost to this day, but fully reconstructable based on the inscriptions on Lintel 22.

The lintel was originally painted red, as were the majority of the monuments within Structure 11, with the exception of Lintel 36 (Maler 1895:fols. 129–130; Morley 1937:II:367). Two of the six extant fragments of the lintel, including the Peabody fragment, have retained the pigment (Graham 1979:77). The previously incomplete data regarding the dimensions of the lintel (Graham 1979:77) can now be largely reconstructed: Maler records an overall width of 64 cm, while Graham reports 65 cm. According to Maler, the width of the sculpted field was 56 cm, whereas Graham estimates it at 55 cm. The original length of the lintel, according to Maler, was 112 cm, with the sculpted area measuring 100 cm. The relief depth is measured by Graham at 0.4 cm, while Maler indicates half a centimeter.

|

| Figure 6. Morley's fragments 1, 2 and 3 of Yaxchilan, Lintel 34 (Photograph cited from Morley 1937-1938:Plate 112e. Public Domain). |

The current state of preservation of the last documented fragments in Yaxchilan is unknown and can only be described on the basis of the available photographic documentation. In his 1979 study, Graham describes the fragment in the Peabody Museum as pristine, while noting that the middle portion of the lintel had already suffered significant erosion when it was photographed by Morley in 1931 (Graham 1979:77) (Figure 6). The condition of the hieroglyphic blocks is, for the most part, satisfactory. With the aid of the previously mentioned comparative inscriptions from Structures 22 (Figure 4) , it is possible to reconstruct those text passages that were eroded on the original or not drawn accurately enough by Maler to identify the individual glyphs with certainty. The current information regarding the whereabouts of the fragments is unavailable; the latest updates on this topic are found in Graham (1979:77; 1982:140). It is assumed that the fragments are still stored in the Yaxchilan bodega, where they should be re-documented during future research to examine additional details in the hieroglyphic text and fill gaps in the interpretation. This will be further addressed in the following section through an epigraphic description and analysis of the lintel, followed by a reassessment of its historical content as reinterpreted through Maler's drawing.

The Narrative Context of Lintel 34

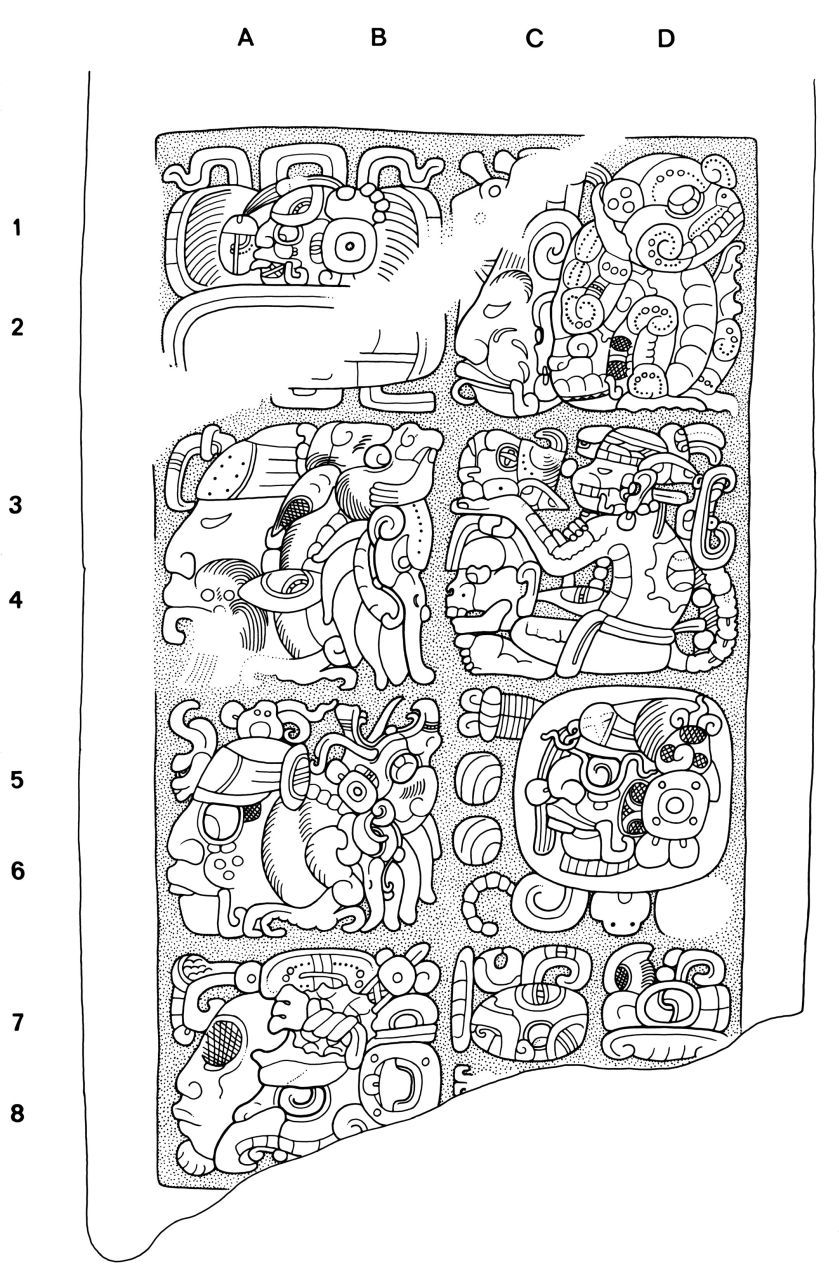

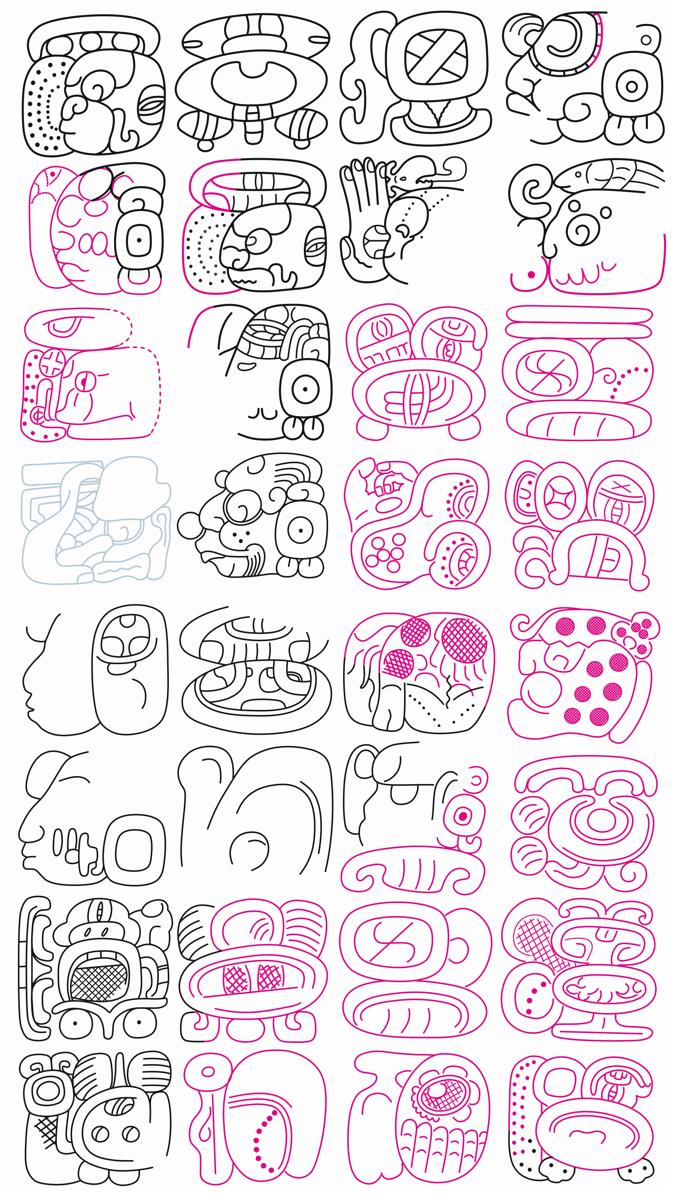

The carved inscription on Lintel 34 comprises 32 hieroglyphic blocks, arranged in a matrix of four columns and eight rows. Prior to the discovery of Maler's drawing, only 18 of these blocks were known to be either partially or fully preserved. The discovery of his drawing has added 13 more blocks to the count, bringing the total to 31. The sole remaining fragment that originally included block A4 is no longer extant but can be tentatively reconstructed from corresponding passages found on Lintel 22 (Figure 2). To fully comprehend the text and context of Lintel 34, it is crucial to recognize that its inscription is part of a broader textual sequence, commencing with Lintel 48 (Figure 7), continuing through Lintels 47 and 34 (Figure 7), and culminating in a royal list and statements of warfare and political hierarchy on Lintels 11, 49, 37, and 35 (Mathews 1988:69ff.) (Figure 3). Thus, understanding Lintel 34 in the context of the monumental dynastic history of Structure 12 necessitates both a thorough examination of its context and its co-texts narrated on Lintel 48, 47, 34, 49, 37, 35 and 36 which together facilitate a precise historical contextualization and a refined reevaluation of Yaxchilan's Early Classic dynastic history.

|

|

|

| Lintel 48 | Lintel 47 | Lintel 34 |

| Figure 7. The dynastic narrative on Lintel 48, 47 and 34 from Structure 12 Yaxchilan (Yaxchilan, Lintel 48, underside, drawing by Ian Graham. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.6.21; Yaxchilan, Lintel 47, underside, drawing by Ian Graham. © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.15.6.6.20; Yaxchilan, Lintel 34: drawing by Christian Prager (2024) after Maler (1897-1900) and Graham (1977, 1982), CC-BY 4.0)). |

||

The analysis of Lintel 34's narrative must begin with the inception of the dynastic narrative presented on Lintels 48 and 47 (Figure 7), marking the accession of KTJ-II on the date 9.4.11.8.16 2 Kib 19 Pax (February 14, 526) (Mathews 1988:91; Martin and Grube 2008:121). His personal name (Colas 2004:288-296), inscribed in the lower hieroglyphic blocks C6-C7, is introduced by a sequence of at least four theonyms ranging from positions A5 to D5 representing this throne name. They include names of animal companions, gods, and patron deities, and are syntactically and semantically interpreted as theophoric epithets of KTJ-II. These theonyms reflect a religious belief among the Classic Maya, wherein animal companions and deities were considered personal patrons of the king, symbolically ascending the throne with him and / or providing protective presence at his enthronement (Colas 2004:288-296).

Thus Lintel 47 presents a comprehensive account of the supernatural beings associated with KTJ-II during his enthronement, including Chak Tahn K'ew (C3-D3), an entity described in ceramic texts as an animal companion (Grube and Nahm 1994:687–688). Furthermore, the supernatural It Paat Yipyajel (B7-C1) is recorded, a figure referenced not only in Yaxchilan but also in early texts from Caracol (St. 23) and Quirigua (St. 26) (B7-C1) (Houston et al. 2017). The subsequent block D1 inscribed the name Oolis K'uh, which is an emic term for a group of deities with specific roles or domains related to the human body (Stuart et al. 1999:II:40; Prager 2013:566–576). Furthermore, Lintel 47 includes additional supernatural epithets associated with KTJ-II. However, the precise readings and identifications of these figures remain unclear. The inclusion of these theonyms in his nominal phrase highlights the king's elevated status and authority, reinforcing his divine legitimacy and his prominent role within the dynastic, historical, and religious frameworks.

The inscription on Lintel 47 culminates with the name of KTJ-II inscribed in hieroglyphic blocks C6-D7, followed by his emblem title in positions D7-D8. This identifies him as a pa'chan ajaw, a ruler of Yaxchilan (cf. Martin 2004). It is noteworthy that the k'uh attribute is absent in this and other instances in the dynastic narrative of Structure 12, with the sole exception of Lintel 34 where it is being used in the context of the k'uh kaajal(?) ajaw statement in position D8. The k'uh attribute, which designates the bearer of an emblem title as a "god-king," serves to underscore the hierarchy between the royal families and the numerous nobles, many of whom were of royal descent (Stuart and Houston 1996:295). In light of this absence, it is worthwhile to consider that pa'chan, or "cleft-sky," may be a toponym and might have served a different function in the king list from Structure 12, specifically as a toponymic title. Grube (2005:98–99) proposes that political entities whose rulers bore toponymic titles rather than emblem titles may have originated as dependencies or colonies of more powerful centers, which employed a complete emblem hieroglyph with the k'uh "god" attribute. It is not yet clear whether this applies to the dynasty in Yaxchilan. Nevertheless, evidence of an early divine kingdom in Yaxchilan can be found not only on Stela 27 but also in the reconstructed text at the end of Lintel 34. In the latter context, KTJ-II is identified not only as the 10th successor of the dynasty's founder, Yopaat Bahlam, but also as the 22nd successor of a god-king from a divine kingdom, Kaajal(?), according to the Emblem glyph in block B8. The latter emblem hieroglyph was subsequently integrated with the well-known pa'chan emblem hieroglyph, which was commonly utilized in Yaxchilan during the reign of Itzamnaaj Bahlam III, to form a double-emblem hieroglyph (cf. Schüren 1992).

Family and Origins

Following the discussion of the epigraphic and historical context of Lintel 34, this section presents a thorough epigraphic analysis, complemented by a historical contextualization of the inscription. The chapter begins with a concise overview of the inscription’s content, which establishes the foundation for the subsequent detailed examination. The concluding section integrates a historical interpretation of the newly uncovered information concerning the early dynastic history of Yaxchilan, illuminated by Teobert Maler's drawing of Lintel 34.

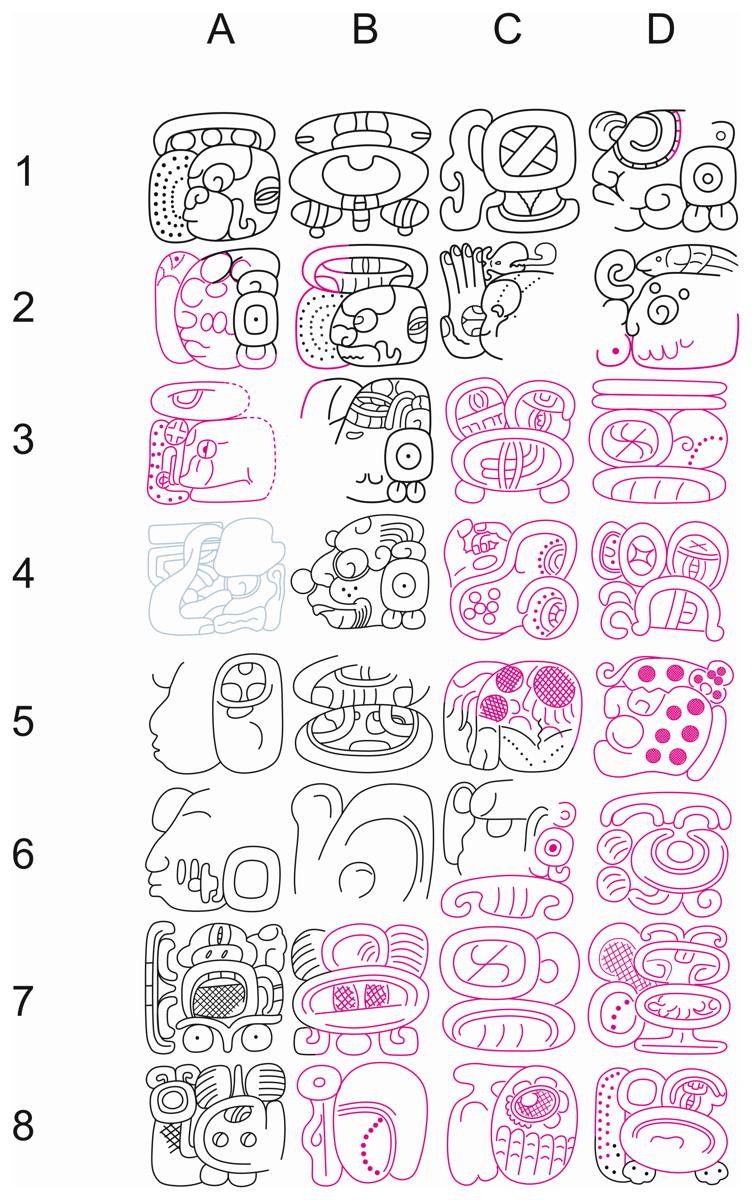

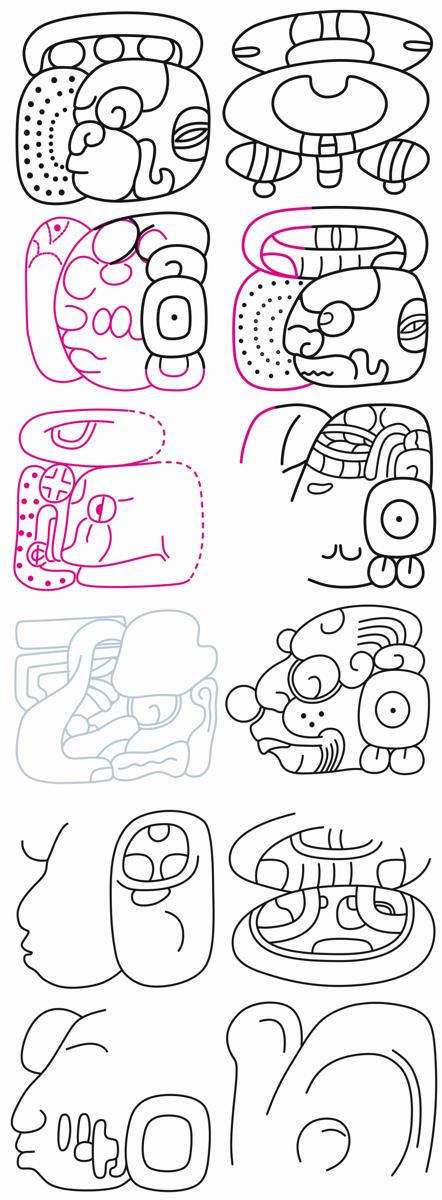

In accordance with the established reading direction of all inscriptions in Structure 12, the narrative that began on Lintels 48 and 47 continues in the inscription on Lintel 34, detailing KTJ-II's family lineage (Mathews 1988:92–93; Kelley 1976:259). To aid in the comprehension of this previously partially deciphered passage, it is noteworthy that the genealogy is similarly recorded on Yaxchilan, Lintel 22 in nearly identical wording or meaning (Figure 4). This parallel allows for the reinterpretation of previously undeciphered or illegible sections (cf. Mathews 1988:92-93) and aids in elucidating the underlying metaphor in the still enigmatic kinship information within hieroglyphic blocks A1-B1, denoting "child of mother," and B6, denoting "child of father" (cf. Mathews 1988:93). Furthermore, the discovery of Maler's drawing enables the reconstruction of previously unknown genealogical details about KTJ-II, which will be explored in the subsequent sections of this article.

|

|

|

|

|

| "Lady Chuwen"'s nominal phrase on Lintel 34 (A1-B6) | "Lady Chuwen"'s nominal phrase on Lintel 22 (A7-D4) | Tikal, Stela 13 (A5-A7), Lady Ahiin from Tikal | Bird Jaguar II's nominal phrase on Lintel 34 (A7-C3) | Bird Jaguar II's nominal phrase on Lintel 22 (C5-D8) |

| Figure 8. Comparison of the parentage statements and nominal phrases of Lady "Chuween" and Bird Jaguar II on Lintel 22 and Lintel 34, and a possible occurence of the parentage statement k'uh chak ohl on Tikal, Stela 13 (Yaxchilan, Lintel 22 (details), drawing by Ian Graham © President and Fellows of Harvard College, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. PM2004.15.6.5.20, all rights reserved; Yaxchilan, Lintel 34: drawing by Christian Prager (2024) after Maler (1897-1900) and Graham (1977, 1982), CC-BY 4.0; Photograph of Tikal, Stela 13, kindly provided by Dmitri Beliaev, Proyecto Atlas Epigráfico de Petén, all rights reserved). |

||||

The inscription on Lintel 34 commences in hieroglyphic blocks A1 and B1 with the linguistically deciphered yet still enigmatic relational expression u k'uh chak ohl, which literally translates to "he is the god from the red heart of" (Figure 8). This metaphor, maybe a kenning to be understood as u-k'uh u chak ohl, is likewise employed in the text on Lintel 22, blocks A7-B7, semantically indicating the relationship of a child to its mother (cf. Mathews 1988:93) (Figure 8)[18]. Continuing to block C1, the inscription of Lintel 22 reveals the nominal phrase for KTJ-II's mother, identified in scholarly research as "Lady Chuen" (Mathews 1988:92) or "Lady Chuwen" (Martin and Grube 2008:119). The proper name and epithets of KTJ-II's father, Bird Jaguar II, are expounded upon in the passage A7-C3 of Lintel 34 (Figure 8). This passage begins with a second enigmatic kinship expression in position A7, linguistically rendered as u yax paw ek', most likely translating to "he is the new star-tail of"[19], a full explanation of this interpretation is offered below. In the corresponding passage on Lintel 22, this metaphor is substituted by the commonly used hieroglyph T535 MIJIIN, signifying "child of father" (cf. Mathews 1988: 93). A discussion of these complex parentage terms and their interpretations follows.

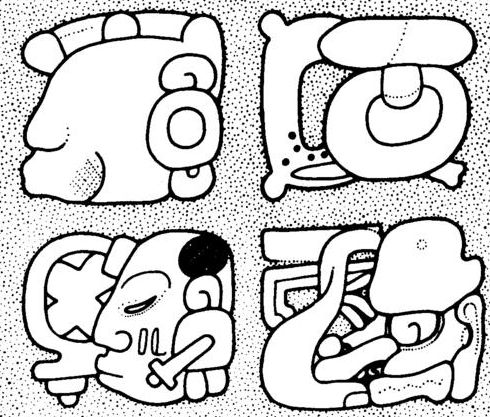

Maler's drawing has facilitated the reconstruction of an entire family saga, culminating in three distinct dynastic sequences following the complex parentage statements of KTJ-II (Figure 12). The first passage, D3-C4, reads lajuun tz'akbuul chihcha' and clearly states that he is the tenth successor since the founding of the dynasty at the legendary place called Chihcha'. The subsequent passage, D4-C6, reads u-yajawte' yopaat bahlam "Yopaat Bahlam is his lord of the spear / tree / lineage'' explicitly places him within the family tree of the dynasty's founder, Yopaat Bahlam.[20] A nearly identical passage with a different spelling of that compound can also be found in the inscription on Yaxchilan, Lintel 21. In this text, Ruler 7, also known as Moon Skull (Martin and Grube 2008:119), is described as the seventh descendant of the Chihcha' dynasty and a scion of Yopaat Bahlam I's dynastic line. In contrast to the detailed rendition of this lineage formula on Lintel 34, the formulation yajawte' chihcha' yopaat bahlam is spelled here in a concise or abbreviated version.

Finally, and this is new information regarding the origins of Yaxchilan' dynasty, in hieroglyphic blocks D6-D8 of Lintel 34, KTJ-II is identified as the 22nd successor of a dynasty founder who is also mentioned on Dos Caobas, Stela 1 (Stuart 2007a:31). Unfortunately, Maler's drawing lacks precision, resulting in only a partial decipherment of the proper name and emblem hieroglyph. Identifying the emblem hieroglyph in position D8 is crucial for understanding the origin of the dynasty in Yaxchilan. Regrettably, the central element of this hieroglyph remains indistinct. However, based on its morphology as depicted in Maler's drawing, it is most likely the sign T1570[21], which can be tentatively read as KAAJ(?) and is associated with the second dynastic line of Yaxchilan (Schüren 1992; Martin 2020:76, 397; Schele and Grube 1994:18; Berlin 1958:112,115). However, this hypothesis is complicated by the presence of the locative suffix -al beneath the enigmatic emblem sign, resulting in kaajal(?).

Evidence that the emblem hieroglyph on Lintel 34 in position D8 represents the Kaaj(?) emblem can be found in a partially eroded inscription on the front of Stela 1 at the small site of Dos Caobas, a few kilometers south of Yaxchilan on the Usumacinta River (Stuart 2007a:31; Cougnaud et al. 2003; Glenn; Tovalín Ahumada 2000; Tovalín Ahumada et al. 1998; Zender; Tovalín Ahumada et al. 1998) (Figure 9). This monument, erected during the reign of Itzamnaaj Bahlam III, provides important information about his ancestry in the lower part of the inscription. According to this inscription, he was the son of "Lady Pakal" and Bird Jaguar III, the 15th successor of the dynasty's founder, Yopaat Bahlam, according to his title phrase. In this context, Bird Jaguar III uses the Pa'chan emblem hieroglyph following the proper name of Yopaat Bahlam I. The following passage, as analyzed by David Stuart and Simon Martin, presents a dynastic census with an ordinal number falling between 20 (Stuart 2007:31) and 30 (Martin 2020:76). According to Nikolai Grube (personal communication, 2024), the decipherment of the coefficient remains tentative due to the partial erosion of this crucial portion of the text. Nevertheless, after examining multiple photographs of the text, the coefficient is most likely 27, as suggested in discussions with Simon Martin, Peter Mathews, and Elisabeth Wagner (personal communications, 2024). This identifies Bird Jaguar III as the 27th successor to an earlier dynastic founder, whose name and title have become almost illegible due to erosion (see drawing in Stuart 2007:31). An examination of the available images suggests that the segment following the succession formula may include signs of the hieroglyph chihcha' for the toponym 'Maguey-Metate,' (cf. Stuart 2014, 2018) followed by a glyph that could represent the emblem or, more precisely, the dynastic glyph of Río Azúl, as deciphered by Stephen Houston (1986). In this context, Bird Jaguar III refers to the second emblem glyph of Yaxchilan, which is believed to read Kaaj(?). It may thus be inferred that the passage on Dos Caobas Stela 1 contains a dynastic formula structurally analogous to that inscribed on Lintel 34. Unfortunately, the identity of the Kaaj dynasty's founder remains elusive in both cases, largely due to the erosion of the relevant portion of text on Dos Caobas, Stela 1 - maybe containing the chihcha' toponym associated with the Río Azul dynastic name - and the absence of crucial diagnostic details in Maler's rendering of the glyphs. Nonetheless, these formal correspondences provide compelling evidence that the emblem glyph in position D8 on Lintel 34 indeed signifies the Kaaj(?) emblem, with KTJ-II recognized as the earliest known bearer of this dynastic title at Yaxchilan.

The reconstruction of key passages from the dynastic text, which may provide insights into possible origins in Río Azul, as referenced on Dos Caobas, Stela 1, remains speculative and requires further validation through on-site examination of the original stelae at Dos Caobas. Nevertheless, the discovery of an additional dynastic count on Yaxchilan's Lintel 34, coupled with the revision of the counts on Dos Caobas, Stela 1, has significant implications for determining the founding date of the El Zotz dynasty. According to calculations by Simon Martin and Peter Mathews (personal communication, 2024), an average reign length of 22.5 years across 22 reigns (21 intervals) results in a cumulative total of 472.5 years. Counting back from KTJ-II's accession in 526 CE, this points to an estimated dynastic origin around 53 CE. With the projected 27th accession of Bird Jaguar III in 629 CE, the kaaj(?) count, spanning 26 intervals or 585 years, suggests a founding date for the El Zotz lineage around 44 CE, aligning with the chronological estimates for KTJ-II.

|

|

| Figure 9. Dual dynastic counts for Bird Jaguar III on Dos Caobas, Stela 1 (back). (Left: drawing by Christian Prager based on David Stuart's drawing and various photographs (2024), CC-BY 4.0. Right: drawing of Dos Caobas, Stela 1, text from the reverse side, bottom, by David Stuart, image cited from Stuart (2007:31). | |

Divine Descent and Royal Lineage

In the preceding analysis of the nominal phrase of KTJ-II on Lintel 47, it was demonstrated that the king is profoundly connected with a pantheon of patron deities, animal companions, and spirits. In Classic inscriptions, the names of supernatural beings are frequently paired with those of kings and their consorts, serving as theophoric epithets from an onomastic standpoint and as throne names from a cultural-historic perspective (Colas 2004:288–296; Grube 2001; Grube 2002; Eberl and Graña-Behrens 2004; Colas 2014). These epithets not only forge a connection between an individual's name or title and their divine attributes but also imply a link to the divine realm and a form of protection, underscoring the veneration accorded to a deity. This practice reinforces the ruler's divine legitimacy and authority, while conveying a complex array of religious and cultural concepts. In essence, the deployment of onomastic practices served to bolster the stability and prestige of ruling dynasties, thereby fortifying their position within the religious and political framework of society.

The close intertwining of governance and divine authority in the dynastic narratives of Structure 12 is illustrated by the theophoric nominal phrases of "Lady Chuwen" and "Bird Jaguar III," as well as by the two metaphorical kinship terms on Lintel 34, which have remained opaque thus far (Figure 8). These examples, in conjunction with the analogous passages from Yaxchilan, Lintel 22, demonstrate that rulers and their consorts were not merely political leaders but also custodians of divine legitimacy, whose authority was reinforced by religious metaphors and metaphysical ideas. Thus, the nominal phrase of "Lady Chuwen" on Lintel 34, in position A2 commences with the most significant social-religious title for royal consorts and concubines, colloquially known as the "inverted vase" title or hieroglyph T182 according to Eric Thompsons catalog (1962) (Figure 8). The evidence known so far concerning hieroglyph T182 reveals a complex picture (Prager 2013:536ff.): those who had this epithet, closely associated with female lunar deities, were high-ranking nobles. They either bore male heirs of a dynastic line or temporarily assumed control during periods of dynastic crisis until a male dynast could reclaim the throne of a city-state. These women, who personified the moon goddess, were responsible for safeguarding and transmitting dynastic authority to their male heirs. This form of legitimization was rooted in religious beliefs and traditions, as evidenced by the account from Palenque, which recounts that in mythical times, the moon goddess transferred royal power in the form of K'awiil to the divine ancestors of the kings of Palenque. Another aspect of interpreting the function and significance of the infamous vase title is its close association with the moon goddess and warfare. In all representations of the so-called warrior queens, these women are depicted as personifications of the moon goddess, who is often portrayed as a flood-bringing destroyer of the world, particularly in Postclassic iconography. The bearers of this title were women who not only gave birth to the male heirs of the dynastic line but also embodied both the old and young moon goddess, thereby representing warlike and destructive aspects as well as creative and life-giving qualities.

The notion that women served as conduits for dynastic authority, transmitting it to their descendants, may shed light on the previously obscure and rare metaphor employed in the relational expression u k'uh chak ohl, found at A1 and B1 on Lintel 34, as well as A7 and B7 on Lintel 22 (Figure 8). This phrase, semantically interpreted to signify "child of mother" (Mathews 1988:92-93), can be literally translated as "he is her god from the red heart." Within the context of birth and motherhood, the term chak ohl (literally "red heart") likely serves as a metaphor for the womb of "Lady Chuwen," the source from which KTJ-II emerged as a divine entity. Consequently, he was endowed with the royal designation k'uh ajaw, best translated as "god-king."

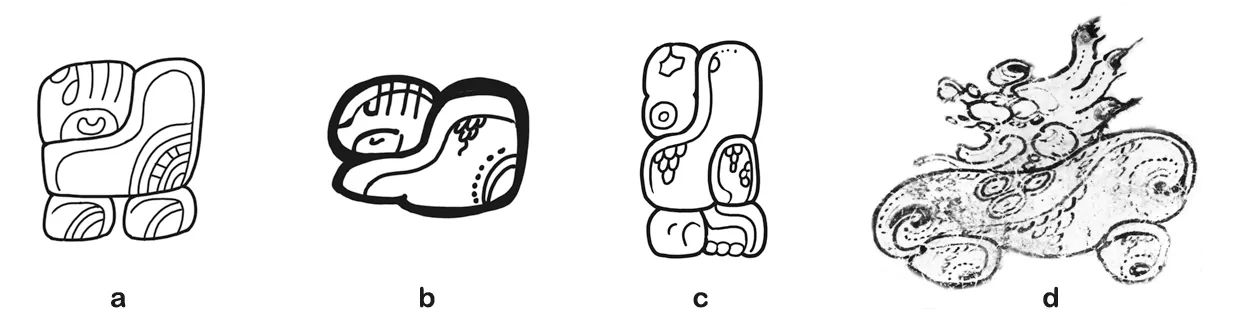

The following passage is associated with the complex nominal phrase that begins at position A2 in the inscription of Lintel 34 and pertains to "Lady Chuwen." This phrase incorporates the terms chan k'uh (sky gods) at B2 and kab k'uh (earth gods) at A3, along with a previously undeciphered term for wind deities located at B3. These terms collectively denote creator deities linked to the elements of sky, earth, and wind. They are known to have served as patron deities to kings and queens, particularly during Late Classic period rituals. These deities participated in ceremonies that recreated the world's creation, initiating new time periods to ensure cosmic and temporal continuity and to reinforce the stability of the dynasty (Stuart et al. 1999:II:43; Prager 2013:504–513). "Lady Chuwen" symbolized this cosmic pantheon, representing the enduring nature of time, the stability of the universe, and the uninterrupted continuity of the royal dynasty. This role is further substantiated by the presence of a theonym within her nominal phrase at A4 and B4 on Lintel 34. The so-called GI title, which remains linguistically undeciphered and is listed in the Thompson catalog (1962) under nomenclature 1028, is of critical importance for interpreting "Lady Chuwen" as the mother of KTJ-II (Figure 9). This title, also found on Lintel 22 and used to reconstruct a gap on Lintel 34 in A4, was typical among high-ranking women in Palenque and Tikal during the Early Classic period (Tuszyńska 2011; Tuszyńska 2017:63–64) (Figure 10). The epithet serves to underscore their exceptional social status and mythological origins, thereby ensuring the continuity of royal dynasties during periods of threatened patrilineal succession, as evidenced by the dynasties of Palenque and Tikal. Tuszyńska (2017:63-64) describes this complex expression as comprising three signs: an upright hand sign, the sign T217d after Thompson (1962) and T1589; the logogram T4 NAH; the grapheme T533 for SAAK(?); and either the head of GI or the sign T1011, the enigmatic deity of water and sun (cf. Stuart 2005:121-122). The linguistic interpretation of the latter sign remains inconclusive. As demonstrated by Tuszyńska, variants of this expression, featuring a dotted version of T533 or the portrait hieroglyph of GI, suggest a close connection to GI and hint at an unresolved complex term that has yet to be linguistically deciphered. In his examination of GI in the context of Palenque's written history, Stuart (2005:161–174) identifies this deity as an opaque figure in Maya iconography and religion, particularly associated with water, and the rising sun, with strong symbolic ties to the concepts of royal ancestry. GI's enigmatic nature is partly attributable to his disappearance at the conclusion of the Classic period, with no discernible connections to prominent Postclassic deities.

|

| Figure 10. A selection of Early Classic spellings of the enigmatic “GI Title”. Left: from a cache vessel of unknown provenance from Peten (drawing by S. Reisinger); center: from cache vessel from Uaxactun (drawing by D. Stuart); right: an incised celt of unknown provenance (drawing by D. Reents-Budet). Image citation from Tuszyńska (2011:Figure 1, this image partially cited after Stuart (2005:121-122), all rights reserved). |

The name "Lady Chuen" was first identified by Peter Mathews on Lintels 22 and 34 (1988:92). However, a comprehensive linguistic decipherment of this name remains an ongoing challenge.[22] Consequently, the epigraphic alias "Lady Chuwen" continues to be used in scholarly literature (Mathews 1988:92; Tate 1992:9; Martin and Grube 2008:119). The name is inscribed on Lintel 34 in positions A5-B6, while Lintel 22 presents a graphic variant between D1 and D2 (Figure 8). The inscription on Lintel 34 consists of the female classifier T1000 IX "woman," the undeciphered sign T1836, the signs T561:23 CHAN-na, and T121, which may be interpreted as LEEM(?), meaning "shining" (Stuart 2007b). Based on the available evidence, it is reasonable to reconstruct the name as IX T1836 CHAN-na T121, though an equally plausible reconstruction could be IX T1836 CHAN-na LEEM. The variant on Lintel 22 displays the sequence T1000, T1836, T561:23, and T121, with an appended suffix that is indiscernible due to erosion. This suffix might represent an unidentified phonetic element that further refines the reading of T121. In the heavily eroded positions A6 and B6 of Lintel 34, a toponymic title may be indicated, offering potential clues to "Lady Chuwen's" political origin and indicating the power center from which she hailed before her integration into the dynastic lineage of Yaxchilan through marriage. To accurately identify the hieroglyphs, the fragments presumably located in Yaxchilan's bodega require more detailed examination; at present, no definitive statements can be made regarding the content of this passage.

The initial segment of the inscription on Lintel 34 concludes in block B6 with the maternal lineage of KTJ-II and then continues in B7 with the previously unidentified kinship term, yax paw ek', which has been semantically construed as "child of the father" (Mathews 1988:93), thereby identifying Bird Jaguar II as the progenitor (Figure 8). The corresponding nominal phrases and lineages delineated on Lintel 22 affirm that yax paw ek' can be substituted with the widely utilized term for "child of the father," mijiin, represented by the sign T535 (Schele, Mathews, and Lounsbury 1982:3). The hieroglyphic sequence on Lintel 34 includes the graphs T1br.[16st:586st].130bh:510bt and is transliterated as u-YAX-pa-wa-EK', transcribed as u yax paw ek'. Although the meanings of u as a possessive pronoun, yax as "new, fresh," and ek' as "star" are well-established, the interpretation of paw continues to be elusive. Within the lowland Mayan language spectrum, paw is found in Yucatec as páawo', where it translates to "net" (Bricker et al. 1998:210), a term likely borrowed from the eastern Maya languages, where paah also denotes "net" and is prevalent in Mayan languages such as Chujean, Q'anjobalan, and K'iche' (Kaufman 2003:978). The semantic connection between ek', "star," and more expansively, "child of the father," however, still warrants exploration. However, it is noteworthy that the lexeme paw is present in Huastec, where it connotes "fire, smoke" (Larsen 1955:44; Ochoa Peralta 1978:7). This suggests that it may be semantically associated with the concept of "star." This hypothetical / speculative association could hint at the fiery tail of a comet, perhaps visible during this or a previous era, potentially serving as a metaphor for the paternity of Bird Jaguar II as documented in the lineage account on Lintel 34. Historical astronomical research could illuminate which comet this might refer to. Should this interpretative hypothesis gain validation, the kinship term u yax paw ek' might be translated and metaphorically understood as "he is the new fiery star (comet) of," signifying "child of the father."

The nominal phrase of Bird Jaguar II, father of KTJ-II, commences in block B7 of Lintel 34 and culminates in position D2-C3 with his name and the toponymic title pa'chan ajaw, translating to "King of Pa'chan (Yaxchilán)". The previous phrase, unfolding in B7-B8, incorporates a so-called K'atun age statement of one K'atun, spelled as [juun] winikhaab, paired with the title ch'ahoom / ch'ajoom, "Scatterer of Incense". The glyph winikhaab ch'ahoom / ch'ajoom can be construed as "scatterer of Incense in his first twenty years of life," providing historical insight into the age reached by the titleholder. Tatiana Proskouriakoff was the first to identify the use of K'atun glyphs with coefficients within nominal phrases and as approximate age indicators outside their calendrical context (Proskouriakoff 1960:472–474; Proskouriakoff 1963:153). This interpretation was expanded by David Kelley and later Berthold Riese, who elucidated that the coefficient of the K'atun glyph denotes the number of K'atun periods elapsed since the individual's birth (Kelley 1976:50; Riese 1980). When paired with a variable attribute or a specific title, K'atun statements form a glyph sequence typically positioned syntactically before the personal name, indicating the office holder's age at a particular moment (Riese 1980:175–177; Gaida 1983:26). In this case, the K'atun statement reveals that Bird Jaguar II reached only the age of 20, suggesting his premature demise. His eldest son, known as Knot-eye Jaguar I, succeeded him. Around 518 CE, he was captured by Piedras Negras. Following his captivity, he governed Yaxchilán as a vassal of Piedras Negras. In 526 CE, Knot-eye Jaguar I was ultimately succeeded by his younger brother KTJ-II. In reaction to the defeat and subjugation of his elder brother by Piedras Negras, KTJ-II commissioned the dynastic narrative within Structure 12, documenting his lineage and the martial achievements of Yaxchilán's kings against the allies and vassals of Piedras Negras.

On Lintel 34 the nominal phrase of Bird Jaguar II resumes in block B8 with a theophoric epithet that encompasses the names of at least one protective deity of Yaxchilán and culminates in block D2 with the proper name of Bird Jaguar II. For more details, see Colas (2004: 271–273). The phonemic reading of this theonym remains partially deciphered. This phrase, associated with the local tutelary deities, was embraced by Bird Jaguar II and his successors, Bird Jaguar III and Bird Jaguar IV. The nominal phrase on Lintel 22, positioned between D5 and C7, clearly parallels this. Lintel 34 includes the theonymic sequence T87bt.528hc for TE'-ku-*yu, T291vs for SIIP (Grube 2012), and T1013st for AK'IIN(?),[21] and the compound 1589st.[86bt:1048st] for mi-xi-NAL, representing the name(s) of at least one or more tutelary deity or deities, Te'kuy, Siip, Ak'iin(?), and Mixnal. Colas (2004: 271-273) definitively shows the crucial role these deities played in the Yaxchilán dynasty, noting their consistent incorporation into the nominal phrases of rulers from the 6th to 8th centuries. In the history of religion tutelary deities frequently appear in the context of kings' personal names across various cultures (Köhler 2003:251, 254). This is primarily to legitimize and reinforce their divine right to rule, symbolize divine protection, emphasize their roles in religious rituals, represent cultural identity and continuity, and serve as a form of political propaganda that enhances their stature as divinely sanctioned leaders. This consolidates power, maintains societal harmony, and ensures the stability and longevity of their dynasties.

Dynastic Origins at Two Places

After detailing KTJ-II's maternal and paternal lineage in glyph blocks A1 to C3 of Lintel 34, block C3 decisively shifts focus to his dynastic position within the rulership established by Yopaat Bahlam (Figure 12). Additionally, KTJ-II’s involvement in another dynastic line, possibly termed kaaj(?), is brought to light. Previously, this lineage had been documented solely on the heavily weathered Stela 1 of Dos Caobas (Stuart 2007a:31; Martin 2020:74). However, the supplementary discovery of the inscription on Lintel 34 now provides a clearer understanding. The passage reconstructed with the help of Maler’s drawing, D3-C4, reads 10-TZ'AK-bu-li chi-CHA' or lajuun tz'akbuul chihcha', clearly indicating that KTJ-II was the tenth successor from the enigmatic Chihcha' site or lineage. The inscription explicitly states that his yajawte', or "Lord of the dynastic line", was Yopaat Bahlam, whose name is clearly legible in C5-D5. This is followed in C6 by a hieroglyph likely representing T1755st:23st or CHUWEEN-na, designating him as a "founder of artistry" (Ciudad Real 2001:41). However, this fragment is significantly eroded, and Maler’s drawing only confirms that the sign T23 na sign is located beneath the largely eroded portrait head. Notably, this passage directly links the Yaxchilán dynasty to the site of Chihcha' (Figure 11). The inscription on Lintel 34 comprises the signs chi for chih ("maguey") and CHA' for cha' ("grinding stone"), which were linguistically deciphered by David Stuart (Stuart 2014; Stuart 2018). The toponym "Grinding Stone for Maguey", documented in approximately twenty texts from the Maya lowlands, is also referred to as "Bent-Cauac," "Place of the Chi Throne," or "Chi-Witz" (Grube 2004:127; Tokovinine 2013:59, 78 database) (Figure 11).

|

| Figure 11. The enigmatic toponym chihcha' in Classic Maya texts according to David Stuart (2014). Examples according to Stuart and description cited from Stuart (2014). Tikal, Altar 31 (a), Vessel of unknown provenance (b), Copan, Stela 4 (d), Kerr 1882 (d). Drawings by David Stuart; photograph by Justin Kerr (d), all rights reserved). |

The etymology of the toponym Chihcha' is deeply intertwined with the rise of the early Maya kingdoms and bears significant historical and legendary associations with a figure known as Yop Huun. The designation Yop Huun is considered the most accurate epigraphic approximation of the original pronunciation of the hitherto undeciphered name. This figure is also known under the aliases "Foliated Ajaw," "Capped-Ahau," "Decorated Ajaw," or "Leaf Ajaw" (Schele 1982:80; Martin and Grube 2008:193). The widespread temporal and geographical dissemination of the name and its related toponym Chihcha' in Maya lowland inscriptions suggests that Yop Huun, or those who bore this name as a title, played a formative role in the institution of kingship, akin to Charlemagne’s role in the foundation and legitimization of European royal houses. The exact identity of the toponym Chihcha' remains elusive, referring to a Protoclassic location whose precise identification has yet to be determined. Potential candidates include El Mirador, Nakbe, or another significant site from the Preclassic period in the central lowlands (Grube 2004:130–131; Stone and Zender 2011:234; Stuart 2014). These sites and the figure of Yop Huun played a crucial role for kings during the early and late Classic periods, serving as central elements in an origin narrative to which later rulers, such as the dynastic founders of Tikal and Calakmul, undoubtedly referred. Lintel 34 clearly demonstrates that even the early Classic kings of Yaxchilán sought to establish a connection to this legendary site or perhaps lineage. Like other early kingdoms, they incorporated the origin narratives of kingship in the Maya lowlands into their historical records, thereby legitimizing their rule by referencing these ancient stories.

|

|

|

|

| Yaxchilan, Lintel 34 (reconstructed) | Yaxchilan, Lintel 34, D3-D8 | Yaxchilan, Lintel 21, C1-D2 | Yaxchilan, Lintel 21 |

|

Figure 12. The dynastic counts and origins on Yaxchilan, Lintel 34 and Lintel 22 (Drawing of Lintel 34: drawing by Christian Prager (2024) after Maler (1897-1900) and Graham (1977, 1982). Teobert Maler's photograph of Yaxchilan, Lintel 22, cited from Maler 1903:Plate XVI. Public Domain). |

|||

A compelling parallel emerges between the inscriptions on Lintel 34 and Lintel 21 from Yaxchilan, particularly in relation to the reign of Yaxchilan's Ruler 7 (Figure 12). The inscription located at positions B8-C2 reads ja-tz'o JOLOOM 7-TZ'AK-bu-li chi-CHA' ya-AJAW-TE' YOPAAT-ti BALAM (Figure 11), which can be translated as "Jatz'oom Joloom / Jatz'o'jol is the seventh successor to Chihcha', dynasty(?) of Yopaat Bahlam'" (cf. Davletshin 2024)[23]. Yopaat Bahlam is revered as the founder of this dynastic lineage, holding the title of yajawte', literally meaning "lord of the spear / captain"[24] and metaphorically "lord of the dynastic line"[25]. The detailed exposition of the dynastic title on Lintel 34, encompassing six hieroglyphic blocks, contrasts with its more succinct expression on Lintel 21. The extensive elaboration found on Lintel 34 now facilitates an accurate interpretation of the inscription on Lintel 21, enabling a correct reconstruction of its full reading sequence and nuanced understanding.

The discovery of a hitherto rather undocumented line of descent at Yaxchilan, as depicted in Teobert Maler's drawing of Lintel 34, has significantly contributed to the reconstruction of a more comprehensive narrative, particularly as illustrated by the positions D6-D8 on Lintel 34. In this passage, KTJ-II is identified as the 22nd successor to the founder of the Kaaj(?) dynasty, a dynastic name that also serves as the emblem of El Zotz (Martin 2020:74; Houston et al. 2018:23). Martin's analysis suggests that paired emblem glyphs (as attested in Yaxchilan and El Zotz) symbolize a synthesis of both older and more recent dynasties and Houston also notes that the titles pa'chan ajaw and kaaj ajaw also serve as titles of the El Zotz dynasty and states a dynastic connection between El Zotz and Yaxchilan "that has yet to be understood" (Houston et al. 2018:23). The inscription on Lintel 34 includes the passage u-2-K'AL TZ'AK-bu-li (D6-C7), followed by a personal name that remains difficult to decipher. This name may refer to the founder of a second, potentially much older dynasty in Yaxchilan. The progenitor's proper name, appearing in position D7, is preserved only in Maler's drawing. However, the drawing's lack of precision complicates the task of definitive interpretation. The hieroglyphic block at D7 contains five glyphs, which may correspond to the sequence pa-ku-cha-TAN?-NAAH, tentatively interpreted as paak chatahn naah, followed by two additional signs in C8. The latter of these could potentially be identified as T582st for MO' "parrot." Nevertheless, this interpretation of the proper name remains speculative and requires further comparative epigraphic analysis or archaeological validation, a matter that will be explored below.

It is particularly noteworthy that, in this context, KTJ-II or the founder is referred to in the final hieroglyph (D8) as k'uh kaajal(?) ajaw ("god-king of Kaajal(?)"). This designation marks a significant departure from the titles held by his father and ancestors in the dynastic narratives of Structure 12, who were identified solely by the toponymic title pa'chan ajaw without the divine attribute k'uh. The earliest recorded use of the title k'uh pa'chan ajaw, or "god-king of Pa'chan," is associated with KTJ-II’s elder brother, Knot-eye Jaguar I. This title is evidenced by the (reworked) inscriptions on Yaxchilan Stela 27, where Knot-eye Jaguar I is noted for having celebrated the period ending 9.4.0.0.0 (514 AD). However, as noted by Martin and Grube (2008:120), the lower third of this stela was damaged in antiquity and subsequently restored and reworked during the reign of Bird Jaguar IV. Consequently, the purported earliest reference to the k'uh pa'chan ajaw title is likely a later addition to the original inscription, which may have been lost during periods of unrest. Knot-eye Jaguar I is also recorded as a captive of Piedras Negras around 518 AD, with his death occurring sometime after 526 AD (Grube 1998). Following his death and in the absence, presumably, of a son to succeed him, KTJ-II assumed the kingship and had the discussed inscription made at the time of his enthronement. The death of Knot-eye Jaguar I and the lack of a direct male successor created a dynastic rupture, which KTJ-II sought to legitimize through the assertion of his divine and royal descent, as prominently declared in the inscriptions of Structure 12. This strategic invocation of divine legitimacy underscores the significant shift in the titles and epithets that KTJ-II employed to reinforce his claim to the throne and restore continuity within the dynasty.

In his comprehensive study of Maya lowland political history, Simon Martin (2020:74), referencing the earlier scholarship of David Stuart (2007:31), also examines the discrepancies within the dynastic enumeration of Yaxchilan, which are further elucidated by the inscription on the reverse of Dos Caobas Stela 1. There, the emblem glyphs pa'chan and kaaj(?) are depicted as double emblems, yet they correspond to different dynastic tallies. Itzamnaaj Bahlam III, who took the throne on 9.12.9.8.1 and passed away on 9.15.10.17.14 (Martin and Grube 2008:123), is acknowledged as the son of Bird Jaguar III, the fifteenth successor in the pa'chan lineage according to Dos Caobas, Stela 1, and, at the same time, the, presumably, 27th in the Kaaj(?) lineage. Martin interprets this as suggestive of a possible dynastic merger, where the succession counts for each lineage were maintained and recorded separately. The inscription on Lintel 34 aligns with this pattern, naming KTJ-II as the tenth ruler of the Pa'chan/Chihcha' dynasty, with Yopaat Bahlam recognized as his forebear and concurrently the twenty-second ruler in the Kaaj(?) lineage. This figure, who presides over the Kaaj(?) lineage, is mentioned not only on Lintel 34 but also on the reverse of Dos Caobas, Stela 1. Unfortunately, the details on Dos Caobas, Stela 1 have been significantly eroded, and Maler's rendering of Lintel 34 lacks the precision needed to definitively ascertain the individual's nominal identity. Nevertheless, a highly speculative reconstruction is offered in Figure 9, which proposes the reading of the chihcha' toponym along with the Río Azul dynastic emblem.

The Dynastic Succession between Ruler 10 and 15

The discovery of two dynastic references in the nominal phrase KTJ-II on Lintel 34, as well as in the king list of Structure 12, suggests that this individual was both the tenth ruler of the Chihcha’ and Pa’chan lineage and the 22nd successor of the Kaaj(?) dynasty. When considered alongside previously known references from the texts of Yaxchilan and Dos Caobas, the dynastic references in the nominal phrase KTJ-II on Lintel 34 provide two new anchor points for analysis. These allow for a more in-depth examination of the dynastic successions of both ruling lines in Yaxchilan. In this context, we extend our gratitude to Peter Mathews for his insightful ideas and dynastic calculations, which he generously shared with the authors (Peter Mathews, personal communication, 2024). The sequence of the first ten rulers of Yaxchilan is well-documented through the lintels of Structure 12. However, the precise numbering of the kings between KTJ-II as the tenth ruler and Bird Jaguar III as the 15th successor of Yopaat Bahlam remains unclear (cf. Martin and Grube 2008:121), as the relevant texts omit the corresponding dynastic counts. According to Stela 1 from Dos Caobas, Bird Jaguar III is identified as both the 15th successor of Yopaat Bahlam and the 27th descendant of the founder of the Kaaj(?) dynasty. Epigraphic sources from Yaxchilan and neighboring sites, such as Bonampak and Palenque, mention three rulers following KTJ-II: Knot-eye Jaguar II, Itzamnaaj Bahlam II, and K’inich Tatbu Joloom III. Mathews summarizes that KTJ-II ascended the throne in 526 AD as the tenth ruler of Yaxchilan and reigned until at least 537, as evidenced by the inscriptions on lintels 35, 47, and 48. After his reign, a gap of 92 years follows before Bird Jaguar III took power in 629. This timespan suggests the existence of four intermediate rulers, assuming an average reign of approximately 23 years (Mathews, personal communication, 2024). One of these rulers, "Knot-eye Jaguar II," is attested for the year 564, placing him as either the 11th or 12th ruler. Another ruler, Itzamnaaj Bahlam II, is mentioned in the years 599 and 600, indicating that he likely served as the 13th or 14th ruler. However, the dynastic progression during this period remains uncertain due to incomplete inscriptions, such as those on Yaxchilan HS. Martin and Grube (2008: 121) hypothesize that K’inich Tatbu Joloom III was the father of Bird Jaguar III. The most plausible succession of rulers places K’inich Tatbu Joloom II as the tenth ruler, followed by "Knot-eye Jaguar II" as the 11th or 12th, Itzamnaaj Bahlam II as the 13th, K’inich Tatbu Joloom III as the 14th, and finally Bird Jaguar III, who ascended the throne in 629 as the 15th ruler of Yaxchilan. Despite the remaining uncertainties and one, presumably, "missing king", this sequence, as reconstructed by Peter Mathews in the course of this study, provides a valuable framework for understanding the dynastic development of Yaxchilan.

| Count of successors since Chihcha' and Yopaat Bahlam I |

Count of successors since Kaaj(?) founder |

Epigraphically attested |

Reconstruction 1 (Mathews, personal communication, 2024) |

Reconstruction 2 (Mathews, personal communication, 2024) |

| #7 | Moon Skull (YAX: Lnt. 21, 49) |

Moon Skull | Moon Skull | |

| #8 |

Bird Jaguar II |

Bird Jaguar II | Bird Jaguar II | |

| #9 |

Knot-eye Jaguar I |

Knot-eye Jaguar I | Knot-eye Jaguar I | |

| #10 | #22 |

K'inich Tatbu Joloom II |

K'inich Tatbu Joloom II | K'inich Tatbu Joloom II |

| #11 | Knot-eye Jaguar III | MISSING? |

||

| #12 | MISSING? |

Knot-eye Jaguar III | ||

| #13 | Itzamnaaj Bahlam II | Itzamnaaj Bahlam II | ||

| #14 | K'inich Tatbu Joloom III | K'inich Tatbu Joloom III | ||

| #15 | #27 | Bird Jaguar III (DCB: St. 1) |

Bird Jaguar III | Bird Jaguar III |

Table 1. A reconstruction of the dynastic count between Ruler 7 and Ruler 15 from Yaxchilan, as interpreted by Peter Mathews (personal communication, 2024).

Summary and Conclusion

The findings of this study offer an advancement in the understanding of Yaxchilan’s dynastic history, particularly through the detailed reconstruction of the hieroglyphic inscription on Lintel 34. The rediscovery of an unpublished drawing by Teobert Maler, housed in the digital archives of the Iberoamerikanisches Institut in Berlin and created during his expeditions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, has presented a unique opportunity to reassess and enhance the epigraphic record of this monument. By integrating Maler’s rendering with previously known fragments, this study has reconstructed all 32 hieroglyphic blocks, thereby addressing long-standing gaps in the textual record. This accomplishment provides new insights into the political, genealogical, and religious dimensions of Yaxchilan’s dynastic history.

The implications of this reconstruction are multifaceted. Notably, it enables a reassessment of Yaxchilan's dynastic lineage, particularly concerning the reign of K’inich Tatbu Joloom II (KTJ-II), a key figure in the inscriptions. The reconstructed text positions and affirms KTJ-II as the tenth successor of the Pa'chan/Chihcha' dynasty, tracing his lineage back to the so called "Ur Classic Site"[26] of Chihcha' and Yopaat Bahlam, the dynasty’s founder in the 4th century CE. This discovery not only bolsters KTJ-II's claim to rulership by emphasizing his direct descent from the city's founding monarch, but also underscores his dual role as the 22nd successor in a secondary dynastic line connected to the Kaaj(?) dynasty, an emblem glyph likely associated with the ancient site of El Zotz (cf. Houston et al. 2018). In correspondence with the authors, Simon Martin highlights that this dynasty likely dates back to the 1st century CE, based on the dynastic counts recorded on Lintel 34 and Dos Caobas Stela 1 (Simon Martin, personal communication, 2024). This dual lineage enhances our understanding of KTJ-II’s position within the local dynastic hierarchy, while also shedding light on Yaxchilan's broader regional connections through intricate interdynastic alliances and rivalries.

The findings also hold broader significance for the study of Classic Maya inscriptions. The detailed analysis of Lintel 34, in comparison with other inscriptions from Yaxchilan and neighboring sites, indicates that the dynastic narrative embedded in Structure 12 was deliberately crafted to present an image of dynastic continuity and stability, even in the face of political upheavals and external challenges. The identification of KTJ-II as both a Pa'chan/Chihcha' ruler and a member of the Kaaj dynasty underscores Yaxchilan’s strategic use of multi-layered dynastic identities. This practice of invoking dual or multiple affiliations, far from unique to Yaxchilan, was a widespread phenomenon across the Maya lowlands, illustrating the complex interplay between local and regional political identities during the Classic period.

Moreover, the evidence from Lintel 34 prompts a reevaluation of the role of Structure 12 within Yaxchilan’s architectural and ritual landscape. The lintels, initially commissioned during KTJ-II’s reign and later incorporated into the structure, were not merely decorative. They served as vital conduits of political and religious ideology. As Megan O'Neil has shown, the inscriptions, including those on Lintel 34, were intended to be read sequentially, guiding visitors through a royal narrative as they approached the building. This architectural configuration suggests that Structure 12 functioned as a monumental narrative space, designed to celebrate and display the history and achievements of Yaxchilan’s rulers. The red-painted hieroglyphs and royal figure depicted on the lintels further amplified the visual impact of the inscriptions, making a compelling statement of dynastic authority and divine sanction.

In conclusion, the rediscovery of Maler’s drawing and the reconstruction of the inscription on Lintel 34 have not only bridged critical gaps in the epigraphic record but have also opened new avenues for understanding the political, genealogical, and religious aspects of Classic Maya rulership. These findings illuminate the complexity of Yaxchilan’s dynastic structure, revealing how its rulers adeptly navigated local traditions and regional political networks to assert their legitimacy and consolidate their power. As such, the study of Lintel 34 contributes to a deeper and more nuanced appreciation of the interplay between power, religion, and history in the Classic Maya world, offering valuable insights into how rulers constructed and projected their dynastic narratives across time and space.

Appendix 1. Transliteration of Yaxchilan, Lintel 34

| A | B | C | D | ||

| 1 | u.K'UH | CHAK:OOL:la |  |

SIIP | AK'IIN(?) |

| 2 | T182 IXIK | CHAN:K'UH | mi.[NAL:xi] | ya.[YAXUN:BALAM] | |

| 3 | KAB:KUH | ??.T1082 | [PA'+CHAN]+AJAW | 10:[TZ'AK.bu]:li | |

| 4 | T1028 | T1011 | chi:CHA' | [u:ya].[AJAW:TE'] | |

| 5 | IX.T1836 | CHAN:LEEM(?) | YOP.AAT | BALAM | |

| 6 | IX.?? | ?? | CHUWEEN(?):na | u:[2.[K'AL:wa]] | |

| 7 | u.[[[YAX:pa].wa]:EK'] | WINIKHAAB(?) | [TZ'AK.bu]:li | [pa:ku].[cha-TAN?:NAAH] | |

| 8 | ch'a.[ma°ho] | TE'.ku.*yu | ??.MO' | K'UH.[AJAW:KAAJ(?):la] |

Table 1. Transliteration[27] of the hieroglyphic inscription on Yaxchilan, Lintel 34 (Concept and drawing Christian Prager (2024), after Maler (1897-1900) and Graham (1977, 1982)).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Peter Mathews, Simon Martin, Albert Davletshin, Nikolai Grube, Elli Wagner, Guido Krempel and Dmitri Beliaev for their insightful contributions and corrections, which significantly shaped and informed the direction of this study. Their feedback and suggestions enhanced both the content and clarity of the work. The authors wish to extend particular thanks to Peter Mathews, whose comments and updated dynastography not only improved the text but also introduced important new ideas regarding the history of Yaxchilan between Ruler 10 and Ruler 15, which we are privileged to cite with his permission. Any oversights or errors in the interpretation and presentation of the data are, of course, solely the responsibility of the authors.

References

Berlin, Heinrich

1958 El glifo «emblema» de las inscripciones mayas. Journal de la Société des Américanistes 47:111–119.

Bricker, Victoria R., Eleuterio Po’ot Yah, Ofelia Dzul de Po’ot, and Anne S. Bradburn

1998 A Dictionary of the Maya Language as Spoken in Hocabá, Yucatán. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Ciudad Real, Antonio de

2001 Calepino Maya de Motul. Plaza y Valdes Editores, México, D.F.

Colas, Pierre R.

2004 Sinn und Bedeutung klassischer Maya-Personennamen: typologische Analyse von Anthroponymphrasen in den Hieroglypheninschriften der klassischen Maya-Kultur als Beitrag zur allgemeinen Onomastik. Acta Mesoamericana 15. Anton Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

2014 Personal Names: The Creation of Social Status among the Classic Maya. In: A Celebration of the Life and Work of Pierre Robert Colas, Frauke Sachse and Christophe Helmke, editors, pp. 19-60. Acta Mesoamericana 27. Saurwein, München.

Cougnaud, Agnes, Hal Green, Bea Koch, and Al Meador

2003 The Dos Caobas Stelae. Wayeb Notes 3:1–9.

Eberl, Markus, and Daniel Graña-Behrens

2004 Proper Names and Throne Names: On the Naming Practice of Classic Maya. In: Continuity and Change: Maya Religious Practices in Temporal Perspective, Daniel Graña-Behrens, Nikolai Grube, Christian M. Prager, Frauke Sachse, Stefanie Teufel, and Elisabeth Wagner, editors, pp. 101–120. Acta Mesoamericana 14. Anton Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

Gaida, Maria

1983 Die Inschriften von Naranjo (Petén, Guatemala). Beiträge zur mittelamerikanischen Völkerkunde 17. Renner, Hamburg.

García Moll, Roberto

2003 La arquitectura de Yaxchilán. Plaza y Valdés: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México, D.F.

Glenn, Sue

2003 Two Stelae from Dos Caobas: Photographs by Sue Glenn. Electronic Document. Mesoweb. https://www.mesoweb.com/reports/Dos_Caobas.html.

Graham, Ian

1979 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volume 3, Part 2: Yaxchilan. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

1982 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volume 3, Part 3: Yaxchilan. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Graham, Ian, and Eric von Euw

1977 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volume 3, Part 1: Yaxchilan. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Graham, Ian, Alexandre Tokovinine, and Barbara W. Fash

2022 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions, Volume 3, Part 4: Yaxchilan. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Grube, Nikolai

1998 Observations on the Late Classic Interregnum at Yaxchilán. In The Archaeology of Mesoamerica: Mexican and European Perspectives, Warwick Bray and Linda Manzanilla, editors, pp. 116–128. British Museum Press, London.

2001 Los nombres de los gobernantes mayas. Arqueología Mexicana 9(50):72–77.

2002 Onomástica de los gobernantes mayas. In: La organización social entre los mayas, Vera Tiesler Blos, Merle G. Robertson, and Rafael Cobos, editors, 2:pp. 321–353. Memoria de la Tercera Mesa Redonda de Palenque. Instituto Nacional de Anthropología e Historia, Méxcio, D.F.

2004 El origen de la dinastía Kaan. In: Los cautivos de Dzibanche, Enrique Nalda, editor, pp. 117–132. Instituto Nacional de Antropologia e Historia, México D.F.

2005 Toponyms, Emblem Glyphs, and the Political Geography of Southern Campeche. Anthropological Notebooks 11(1):87–100.

2012 A Logogram for SIP, "Lord of the Deer". Mexicon 34(6):138-141.

Grube, Nikolai, and Werner Nahm

1994 A Census of Xibalba: A Complete Inventory of Way Characters on Maya Ceramics. In: The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases; Volume 4, Barbara Kerr and Justin Kerr, editors, pp. 686–715. Kerr Associates, New York, NY.

Houston, Stephen D., Thomas G. Garrison, and Edwin Román

2018 A Fortress in Heaven: Researching the Long-Term at El Zotz, Guatemala. In: An Inconstant Landscape: The Maya Kingdom of El Zotz, Guatemala, Thomas G. Garrison and Stephen D. Houston, editors, pp. 3–45. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, CO.

Houston, Stephen D., David S. Stuart, and Marc Zender

2017 The Lizard King. Maya Decipherment. https://decipherment.wordpress.com/2017/06/15/the-lizard-king/.

Kaufman, Terrence

2003 A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI). http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/pmed.pdf.

Kelley, David H.

1976 Deciphering the Maya Script. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Köhler, Ulrich

2003 Aztekische Religion. In: Handbuch Religionswissenschaft: Religionen und ihre zentralen Themen, Johann Figl, editor, pp. 245–258. Tyrolia-Verlag ; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Innsbruck, Wien, Göttingen.

Larsen, Ramón

1955 Vocabulario huasteco del estado de San Luis Potosí. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, Mèxico, D.F.

Maler, Teobert

1895 Paises adyacentes de las ruinas antiguas de la civilización Maya [1895-1900]. Unpublished Manuscript. Berlin. Nachlass Teobert Maler. Iberoamerikanisches Institut. https://digital.iai.spk-berlin.de/viewer/!toc/104926973X/209/-/.

1897-1900 Archäologische Pläne und Skizzen: Yaxchilän [Lorillard-City]: Plano compuesto, Edificio: 6, 18-23, 30, 33, 39, 40, 42, 44 Dinteln 18-23, 29-34 (1897-1900), accessible at [https://digital.iai.spk-berlin.de/viewer/image/1664559647/] and https://digital.iai.spk-berlin.de/viewer/!image/1664559647/41 / [accessed 18 July 2024].

1903 Researches in the Central Portion of the Usumatsintla Valley: Report of Explorations for the Museum 1898-1900 [Part 2]. Vol. 2. Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 2. Peabody Museum, Cambridge, MA. http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101060780507;view=1up;seq=5.

1997 Península Yucatán. Editors Hanns J. Prem and Ian Graham. Monumenta Americana 5. Mann, Berlin.

Martin, Simon

2004 A Broken Sky: The Ancient Name of Yaxchilan as Pa’ Chan. The PARI Journal 5(1):1–7.

2020 Ancient Maya Politics: A Political Anthropology of the Classic Period 150–900 CE. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube

2008 Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. 2nd edition . Thames & Hudson, London.

Mathews, Peter

1980 Notes on the Dynastic Sequence of Yaxchilan. Unpublished Manuscript.

1988 The Sculpture of Yaxchilan. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Morley, Sylvanus G.

1931 Sylvanus G. Morley’s Diary of the Fourteenth Central American Expedition of the Canegie Institution of Washington, 1931. Unpublished Transcript by Peter Mathews, provided to the authors, 2024.

1937 The Inscriptions of Petén. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 437. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C.

Nahm, Werner

1997 Hieroglyphic Stairway 1 at Yaxchilan. Mexicon 19(4):65–69.