und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

Stela 64: A New Epigraphic Discovery at Copan, Honduras

Research Note 31

September 27, 2024

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.24.rn031.en

Christian M. Prager (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Elisabeth Wagner (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Seiichi Nakamura (Komatsu University)

Introduction

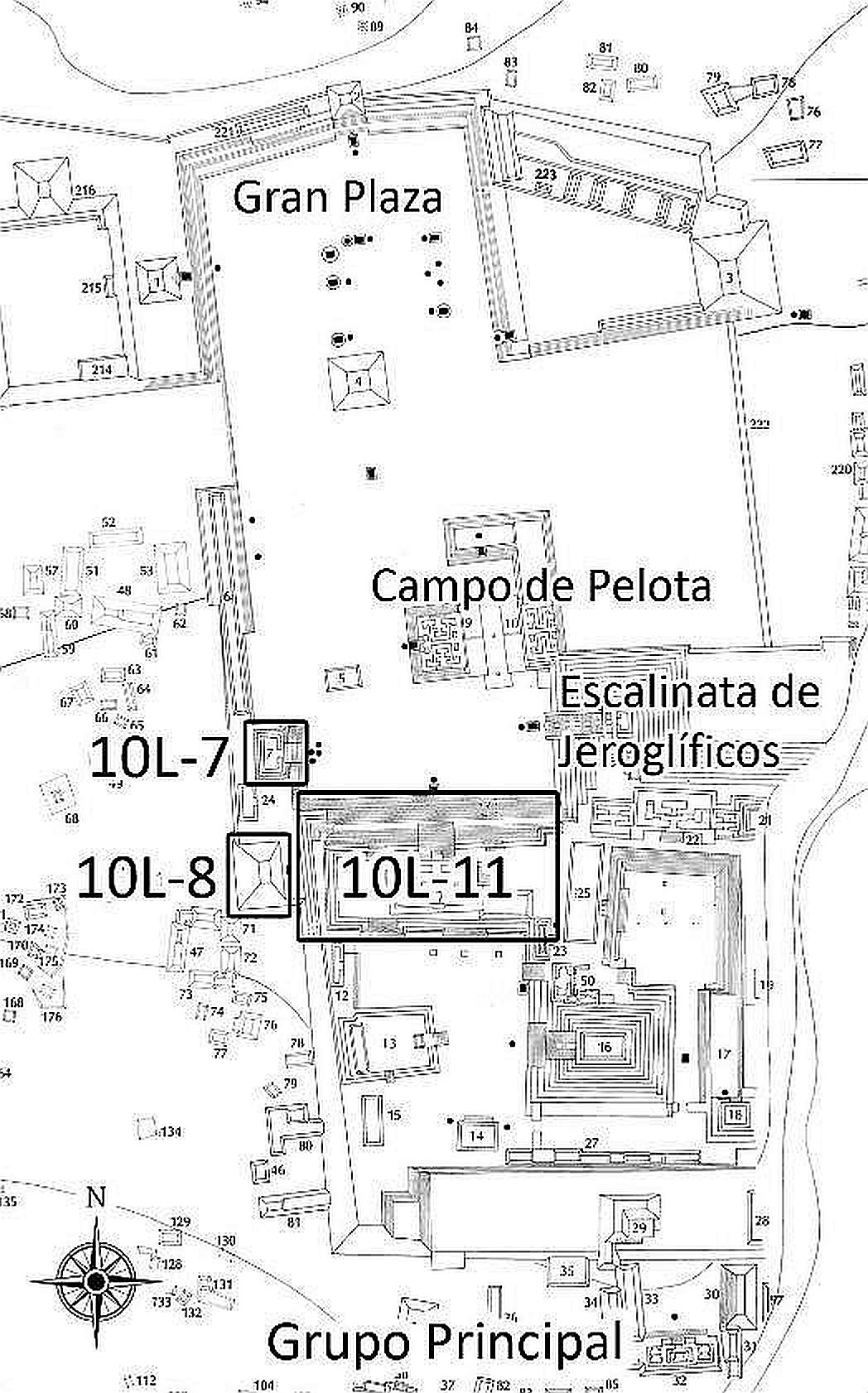

In March 2024, as part of the PROARCO II project (Nakamura et al. 2021) directed by Seiichi Nakamura, a remarkable fragment of an Early Classic stela with hieroglyphic inscription was discovered at the archaeological site of Copán, Honduras, on the western side of the platform of Structure 10L-11 (Figure 1). This monument, designated Stela 64, bears the calendrical date 9.1.10.0.0 (July 7, A.D. 465) on its front and, with the mention of Rulers 4 and 6 on the reverse, can be placed in the early dynastic history of this site. Examination of the inscription shows that the date 9.1.10.0.0 is associated with the ruler K'altuun Hix, or Ruler 4, while the stela was probably erected during the reign of Ruler 6, who is associated with the date 9.3.0.0.0 (January 31, A.D. 495) on Copán Stela 28. It can be assumed that Stela 64, with its partially retrospective text, was created in the context of this end of K'atun.

The fragmentary monument (Figures 2-4) represents the first significant new discovery of a Maya inscription at Copán in over 35 years and, with its inscription only partially preserved, provides new insights into the early dynastic history of this important Maya city, about which comparatively little contemporary material and historical information is available (Martin and Grube 2008:192-97; Prager and Wagner 2017; Stuart 2004). Any discovery of early inscriptions at Copan is of utmost importance for epigraphic and historical research, as it provides contemporary information on the early dynastic history of this important site in the southeastern Classic Maya Lowlands. In this article we will describe in detail this important new discovery, analyze it exhaustively and place it in its cultural-historical context to better understand the early dynastic history of Copán.

|

|

|

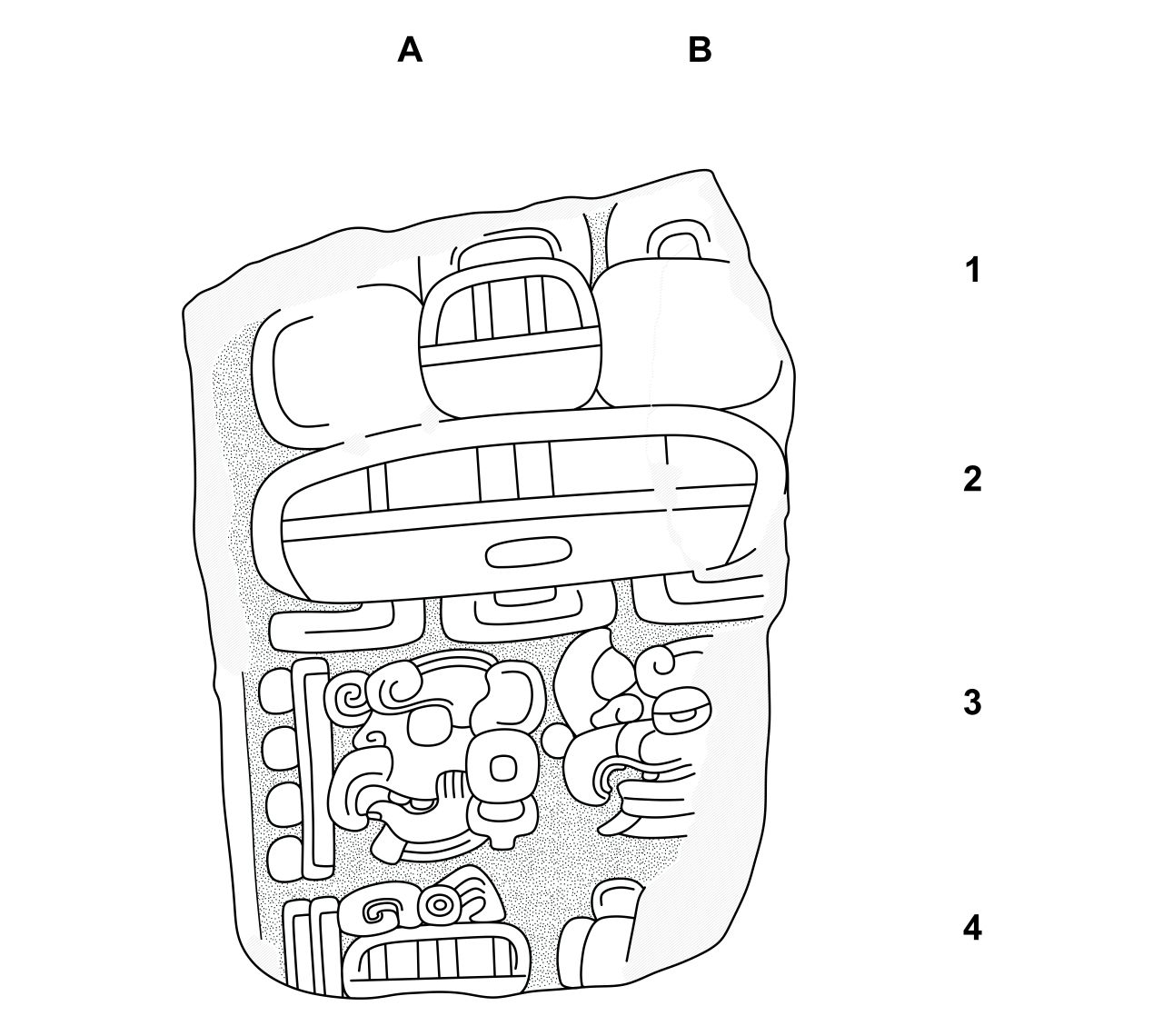

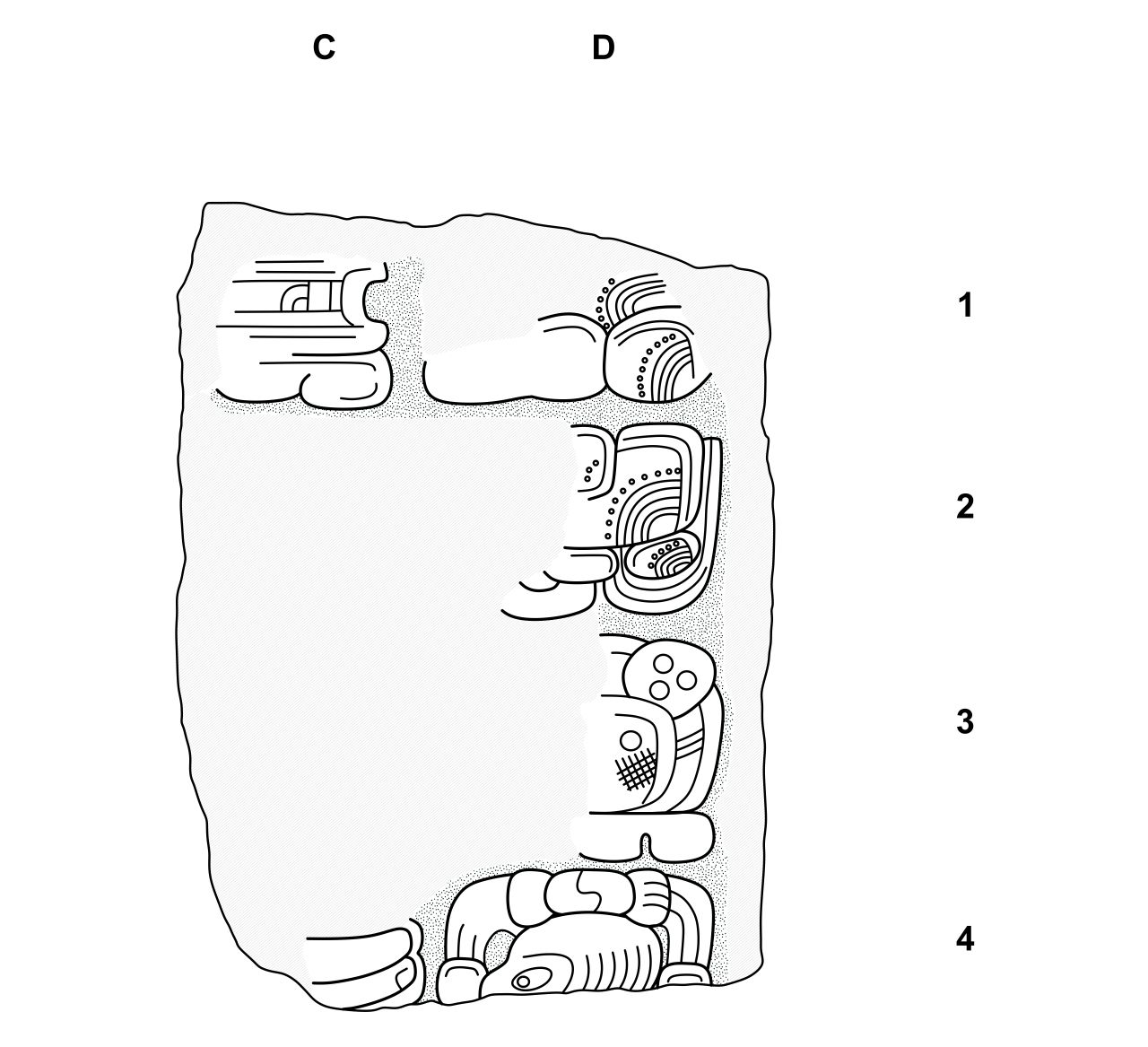

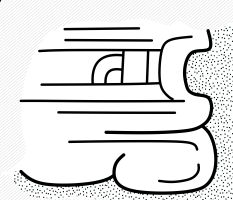

Figure 2. Copan, Stela 64, front side (Drawing by Christian M. Prager, 2024[1]; photograph by Seiichi Nakamura, 2024, all rights reserved). |

|

The present fragment represents the upper half of a stela that was originally at least twice the height and shows low-relief inscriptions, some of them very eroded, on its front and back, as well as on the left narrow side (Figures 2-4). It was probably a monument with pure inscriptions, characteristic of the Early Classic period in Copán (Schele 1990). Due to its state of preservation, it is no longer possible to determine with certainty whether the partially broken right narrow side once bore an inscription as well.

Like all the other monuments at Copán, the fragment of Stela 64 in question is carved from the local volcanic tuff. It is 66 cm high, 48 cm wide and 34 cm thick. The original height of the stela is estimated to be at least 120 cm, a reconstruction that is based on the preserved and reconstructable calendrical inscription on the front, as well as on comparison with contemporary monuments of similar design. Despite considerable damage, it is possible to identify and decipher large parts of the inscription on both the front and back, thanks to the use of 3D-models. For example, three hieroglyphic blocks on the front are complete, and two are partially preserved, while six of the eight hieroglyphic blocks on the reverse are partially legible, allowing a comprehensive understanding of the inscription.

|

|

|

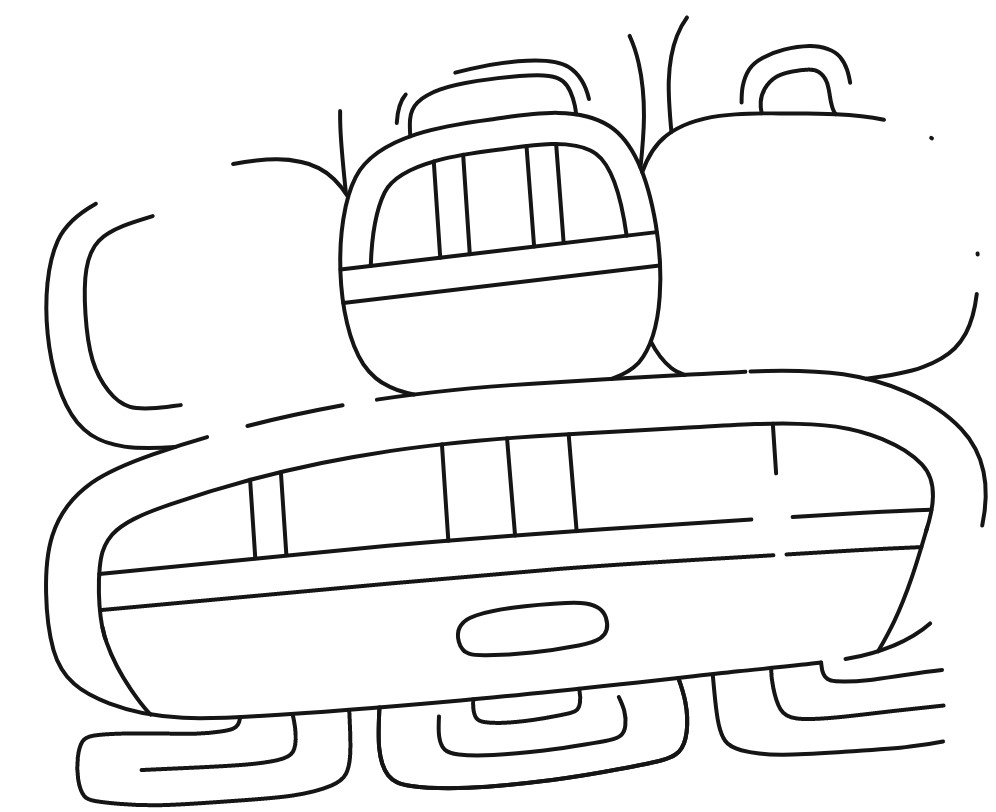

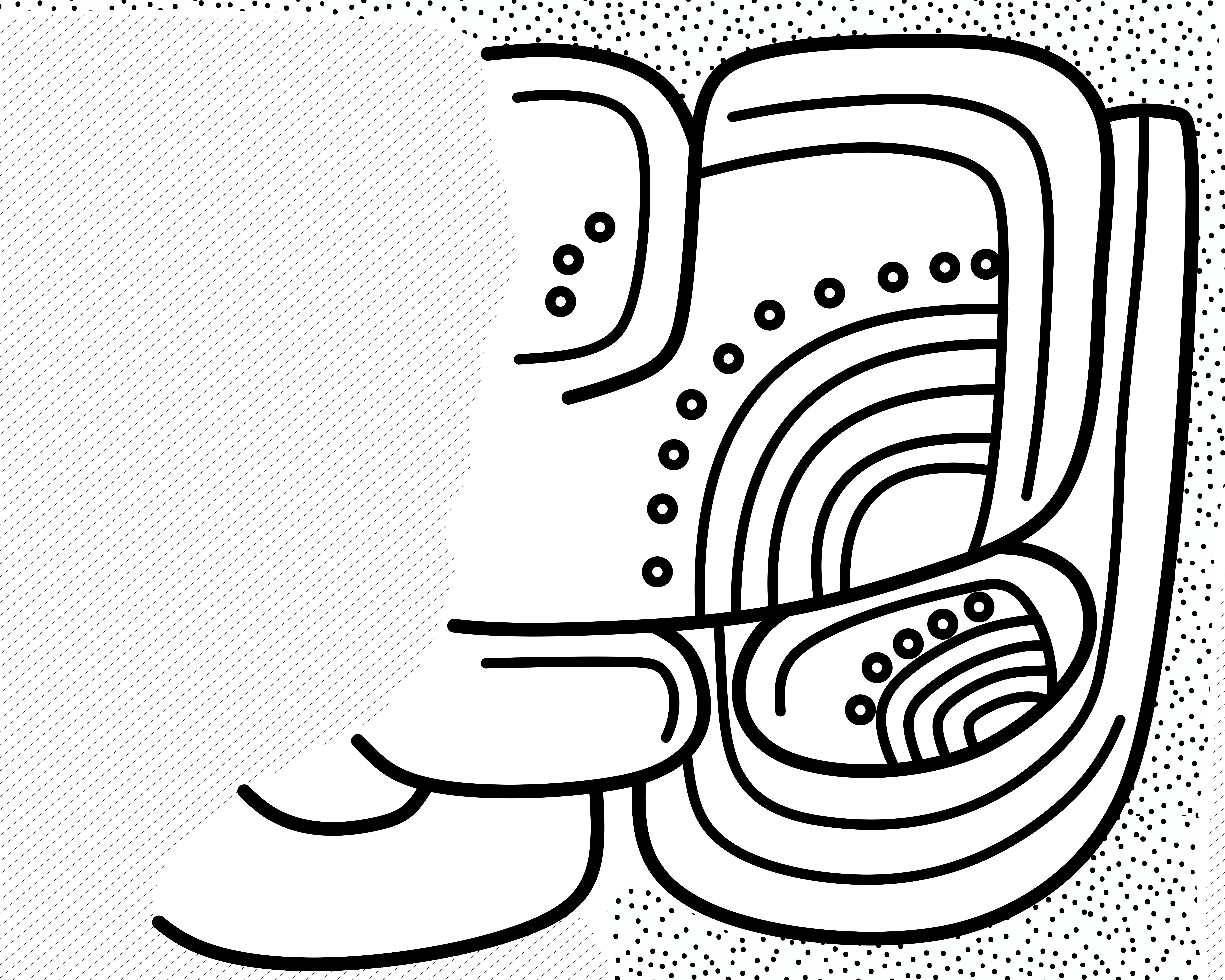

Figure 3. Copan, Stela 64, back side (Drawing by Christian M. Prager, 2024; photograph by Seiichi Nakamura, 2024, all rights reserved). |

|

Stela 64 was discovered on March 4, 2024 during survey work between Structure 10L-11 and the adjacent Structure 10L-8 north of the modern stairway to the west side of Structure 10L-11. The fragmentary monument was found reused as construction material on the west wall of the second platform of Structure 10L-11, which was covered by earth, weeds and moss. Stratigraphically, the fragment can be assigned to an aggregation/annex that had been added to the northwest corner of the front façade of Structure 10L-11 whose front façade dates to the reign of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, the sixteenth ruler of the Copan dynasty. However, PROARCO II’s investigations revealed that his modification of Structure 10L-11’s façade by constructing this aggregation (annex) was part of the same building campaign which further included the modification of Structures 10L-8 and 10L-7. During this campaign Yax Pasaj’s version of Structure 10L-7 was demolished and its architectural sculptures were shattered and re-used as construction fill in the succeeding and final construction stage of Structure 10L-7. Therefore, it can be assumed that these modifications postdate Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat’s reign. However, the violent treatment of the architectural sculptures from Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat’s version of Structure 10L-7 argues against Yax Pasaj’s successor, U Kit Took’, whose only monument, the unfinished Altar L, indicates his reverence towards Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat. This monument not only follows the same style and canon of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat’s great dynastic monument, Altar Q, but also depicts Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat as a revered predecessor and ancestor from whom U Kit Took’ receives the sanction to rule.

|

|

|

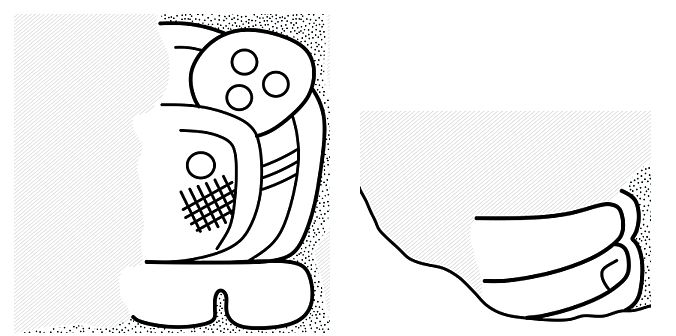

Figure 4. Copan, Stela 64, left and right sides (Photographs by Seiichi Nakamura, 2024, all rights reserved). |

|

It is not clear who was in charge of these late construction activities, but it seems that this actor was not positively inclined towards Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat. On this background, various questions raise: Did the demolition of the penultimate version of Structure 10L-7 occur in the context of the same socio-political turbulences which left Altar L unfinished? Did another - yet unknown - successor emerge after the fall of U Kit Took’ to continue or re-establish dynastic rule at Copan before the final collapse? That potential successor might have been responsible for the final version of Structure 10L-7 and the other mentioned modifications. However, unambiguously dated (epigraphic) evidence for such a successor has yet to be found. Despite its find context belonging to the last phase of construction, the style of Stela 64 is clearly Early Classic. The discovery raises the question of the source from which the builders obtained the monument before it was reused for the final decoration of Structure 10L-11. Notably, in the excavation at Structure 10L-7, stucco decorative elements were discovered, which were the remains of an early building with stucco decoration, dated by 14C analysis to between 425 and 545 cal A.D. (IntCal 20; 2σ, probability 95.4%). However, this building had been completely demolished and covered by later superstructures, suggesting that structures were already in place at the nearby site in the fifth century to the first half of the sixth century A.D. based on the 14C dating result.

Secondary Use of Stela 64

The early style of Stela 64, its fragmentary state and its reuse as building material in a later structure clearly classify it as spolia. This term, derived from the history of art and architecture, refers to the components and decorative elements of ancient buildings that are reused in new construction and to this behavior as a specific cultural practice (see Esch 1969; Kinney 2019). The practice of dismantling earlier monuments to reuse their fragments in later buildings is widely documented at Copan. Fragmentary monuments have been found both in the main site core and in peripheral areas, such as Las Sepulturas and the archaeological site at the site of the modern town of Copán Ruinas, in clearly secondary precolonial contexts (Gordon 1902; Strømsvik 1941; Baudez 1983; Schele 1987; Webster 1989:22-24, Figures 10-11; Schele 1990; Baudez and Riese 1990; Andrews and Fash 1992). These monuments, mostly from the Early Classic period, provide valuable evidence for the dynastic history of that time. The secondary contexts in which they were found show a wide variety in the treatment and use of these monuments or architectural sculptures after they were removed from their original location. Practices range from ritual deposition as offerings to their use as fill material in remodeling, complete reuse of the monuments in their original function, their transformation into other types of monuments, and the integration of fragments as spolia in exterior walls, foundations, or near the ground surface.

However, the question of when and where these monuments were removed, destroyed, and stored after their destruction, before being reused in buildings at Copán throughout the Late Classic period, remains unresolved. Evidence of extensive destruction in the Copán acropolis area in the mid-sixth century A.D., according to Robert Sharer (Stuart 2004; Bell, Canuto, and Sharer 2004:147, 149), suggests that a considerable number of Early Classic monuments were affected. However, no "stelae cemetery" or similar site intended for the systematic deposition of stela fragments has yet been discovered. Therefore, it remains unclear whether all Early Classic period monuments were destroyed in a single event and whether they have been reused multiple times through successive demolition and construction works. With the exception of Stela 63, which was erected inside the Motmot/Papagayo structure and then dismantled, with its top deposited inside the building and its base remaining in its original location (B. W. Fash 2004:76), the original contexts of most of the monuments found as spolia remain unknown. The Xukpi Stone is a notable exception, as it was found in its entirety as fill material in the Margarita structure (Sedat and Sharer 1994:1-2; Stuart 2004:244). However, based on its inscription, its original location can be identified as the tomb of Ruler 2 (Prager and Wagner 2017). Similarly, the Azul Stone, which originally marked the shrine over the tomb of dynasty founder K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo', was completely removed from its original context and reintegrated into a stair step in a later version of the founder’s ancestral shrine (Agurcia Fasquelle and Fash 2005:209; Ramos Gómez 2006:68; Prager and Wagner 2017). All other Early Classic monuments, including the recently discovered Stela 64, were removed from their original locations, destroyed, or reworked into building stones to be eventually integrated into wall fill, stela foundations, masonry, or steps.

The relevance of spolia transcends purely practical considerations, according to which previously worked stones from demolished buildings and destroyed monuments can be conveniently reused as building material; symbolic aspects also play a crucial role in their use (Eaton 2000:135; Kinney 2019:332). Jesper Nielsen argues that the reuse of pre-Columbian sculpted stones with specific iconographic motifs in colonial buildings in Yucatán was intended to maintain a semiotic continuity between the old and the new religious structures (Nielsen 2013, 2020:1-2, 6). Nielsen also suggests that the visible placement of spolia in colonial-era Christian buildings at Izamal and other Yucatán sites represents an early example of the ethnographically documented practice of integrating pre-Hispanic artifacts into sacred contexts, such as domestic altars (Nielsen 2020:9). This could indicate that the Maya recognized these objects as works of their ancestors and sought to create a link to the past, regardless of their original content (Nielsen 2020:12). This practice can be interpreted as a cultural survival strategy on the part of the colonial Maya (Nielsen 2020:11). An example of this strategy, according to Nielsen, is the desire of the Izamal Maya to build the monastery on the site of the temple of the local deity Ppap Hol Chac, as recounted by Diego de Landa (Landa 1941[1566]:173; Nielsen 2020:6).

The use of spolia by the pre-Hispanic Copán Maya reflects an intention similar to that observed in other cultures, seeking to maintain continuity despite socio-cultural changes, whether brought about by the Spanish colonial period or the socio-political upheaval of pre-Hispanic Copán. This practice was intended to preserve a direct link with the ancestors and to manifest a dynastic continuity. In times of political turmoil and crisis, the incorporation of "ancestral relics" could be interpreted as a means to establish tangible connections with the ancestors and thus demonstrate the durability of the dynasty. These "relics" not only include Early Classic objects from the dynasty's founding period, such as the pectoral deposited in the dedicatory deposit of the hieroglyphic stairway of Structure 26 (W. L. Fash 1988:165-66, Figure 6a; 2001:148), but also the symbolic burial of the superstructure of the sanctuary of the founder of the dynasty, K'inich Yax K'uk' Mo' (Agurcia Fasquelle, Stone and Ramos 1996:198; Wagner 2006; Agurcia Fasquelle 2007:66-67). Likewise, this practice extends to the special architectural integration of buildings and monuments of Ruler 13's building program carried out by his successors, especially Ruler 16 (Wagner 2016). Ultimately, this includes the placement of fragmentary Early Classic monuments as spolia in the context of later constructions and monuments, underscoring the ongoing effort to connect the present to the past through material and symbolic structures.

The Hieroglyphic Text

Stela 64 presents a total of 14 hieroglyphic blocks distributed on its wide (front: A1-B4; back: C1-D4) and narrow sides, two of which are illegible due to significant damage (Table 1). On the fragmentary right side (Figure 4b), no traces of writing or iconography are recognized; however, it is presumed that it originally contained text, based on analogy with comparable monuments from Copán. The appearance of the front of the stela (Figure 2) is dominated by the striking introductory hieroglyph of the Initial Series (A1-B1), which extends horizontally across two hieroglyphic blocks. Below this, four hieroglyphs are arranged in a double column featuring a date in Long Count notation (A2-B3). This design marks the beginning of the text, which should continue at the bottom of the stele and extend to the reverse and narrow sides.

| front | ||

|

A1-B2 |

|

|

|

A3 |

|

B3 |

|

A4 5010st.548bv LAJUUN HAAB |

|

B4 |

| The patron of the month Zec is Chan, on the day 9.1.10.0.*0 [...] | ||

| reverse | ||

|

C1 |

|

D1 |

|

C2 [...] |

|

D2 |

|

C3 [...] |

|

D3 |

|

C4 |

|

D4 |

|

[...] *Uh Chan Ahk (Ruler 6), divine(?) king of Copan [...] the Maguey-Stone-Place [...] said it, K'altuunhix (Ruler 4), of the Río Azúl dynasty [...] |

||

Table 1. Transliteration, transcription and translation of the hieroglyphic text of Copan, Stela 64 (Drawings by Christian M. Prager)[2].

The beginning of the inscription on Stela 64 is visually marked by a double-sized hieroglyphic block in position A1-B1, which contains the so-called introductory hieroglyph of the Initial Series, although it shows damage on the right edge (Table 1). This hieroglyph, with a height of approximately 34 cm and a width of 44 cm, is thus twice as large as the other hieroglyphic blocks on the stela. As a calendrical reference hieroglyph, it includes a variable element, in this case the sign T561 CHAN, which in this context indicates the month Zec. The hieroglyph is formed by the graphemes [T124bv°561st]:548bv and is only partially deciphered linguistically as T124-CHAN-HAAB. It introduces the so-called Long Count, composed of the elements 5009st.1033st BALUUN PIK (A2), 5001st.746st JUUN CHAN (B2), 5010st.548bv MIH HAAB (A3) and 173st.??? MIH *WINIK (B3), representing the calendar date 9.1.10.0.0. This date was originally continued on the lower part of the stela and contained the hieroglyph for the K'IN time period with coefficient in the *A4 positions and a Tzolk'in date in *B4. Due to its fragmentary state, the date and other calendar details are missing. However, it is very likely that the date is 9.1.10.0.0, corresponding to *5 *Ajaw and *3 Zec, thus marking the end of a period, which translates to the Gregorian date of July 7, A.D. 465 (Martin-Skidmore-Correlation). The month of Zec can be reconstructed, since it is mentioned as a month patron in the introductory hieroglyph of the Initial Series (A1-B2). A comparison with the chronology of the Early Classic monuments of Copan shows that Stela 64 also documents a Period Ending, set at the date 9.1.10.0.0, which is also noted on Stela 20 and was reconstructed by Sylvanus Morley on the basis of the Lunar Series (Morley 1920:72-73) (see Figure 8c). According to the arithmetic calculation of the calendar, Long Count dates from 9.1.10.0.1 to 9.1.10.0.16 would also be possible. However, the fact that the stelae of the Early Classic period at Copán evoke, in particular, ceremonies related to the half periods, such as 9.1.10.0.0 (Stela 20), 9.2.10.0.0 (Stela 24), 9.3.10.0.0 (Stela 15), 9.4.10.0.0 (Stela 15) or 9.5.10.0.0 (Stela E), makes it is very likely that Stela 64 refers to the half period date 9.1.10.0.0.

It is very likely that the text on the front not only ended with the month 3 Zec, but also included a verb describing an event related to the end of the period or the erection of the stela, as well as the proper name of the corresponding protagonist. This name of the protagonist is inscribed on the back of the stela (Figure 3), where eight hieroglyphic blocks are found in positions C1-D4. Unfortunately, two of these blocks are completely destroyed (C2, D3), and the remaining ones are only partially preserved and show remarkable erosion in some places. A fragment of the relief border of the inscription is preserved next to the hieroglyphic block D4 (Figure 4).

The state of preservation of the inscription on the reverse (Figure 3) is sufficient to decipher the text and understand the historical context. The hieroglyphic block C1 contains the hieroglyph [626st+561st]:23st CHAN-na AHK, followed by the Copan emblem hieroglyph in D1. Of particular note is the grapheme T1538st, maybe KIP, characteristic of the Copan emblem hieroglyph, complemented by T177 pi, which is usually added to this sign to represent the dynastic name of Copan as KIP, as suggested by Péter Bíró, Nikolai Grube, Guido Krempel, Christian Prager and Elisabeth Wagner in 2010 in an unpublished interpretation of the sign T1538.

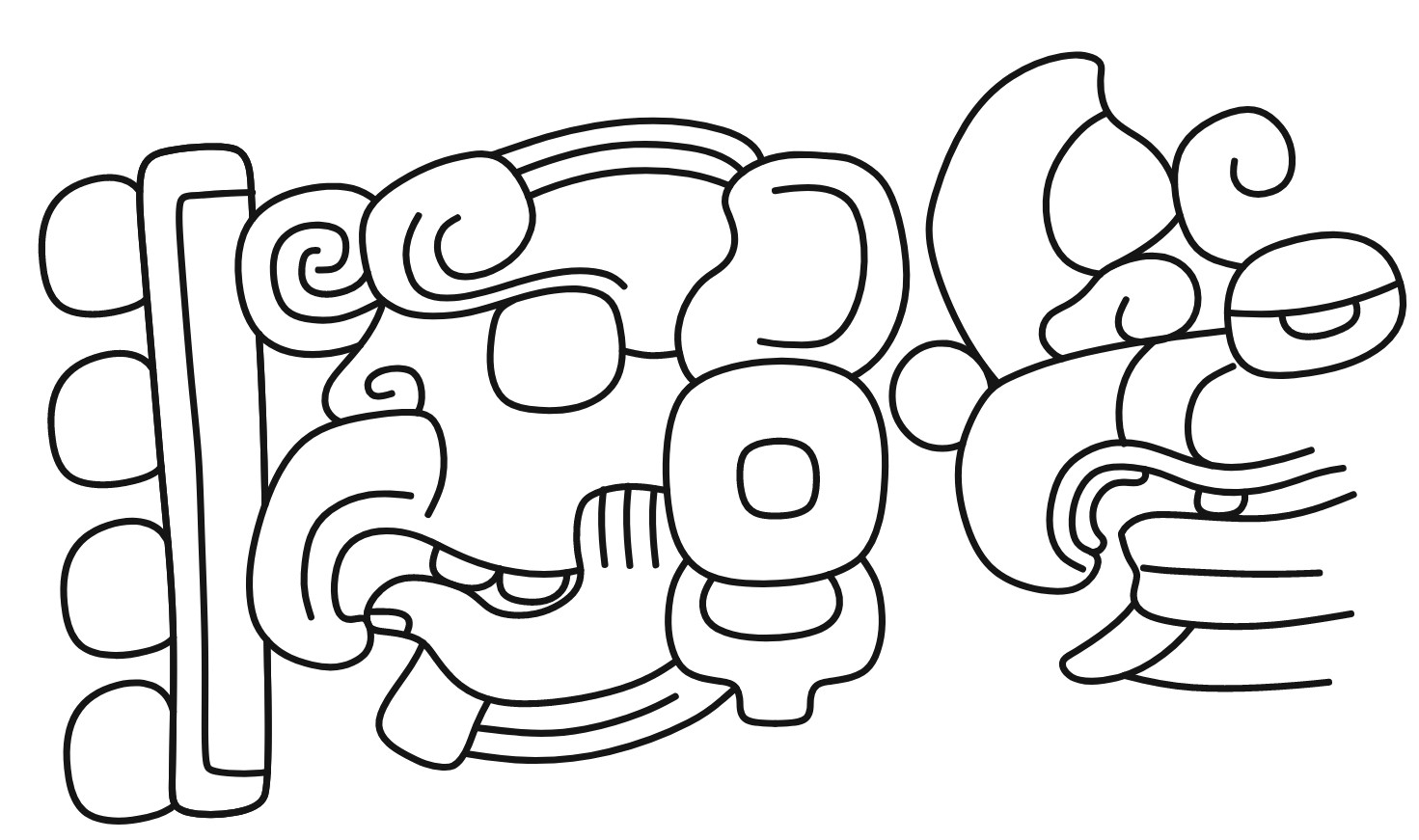

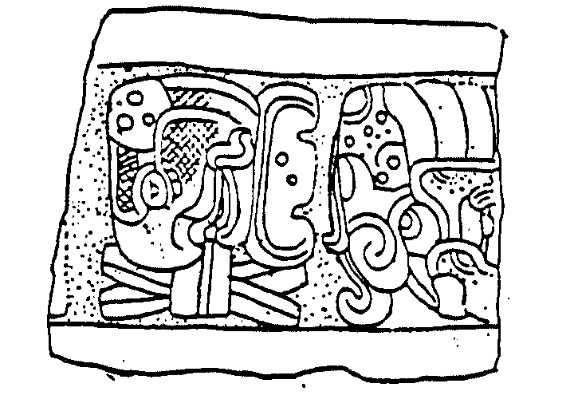

The only Copán ruler to include the element Chan Ahk in his name is Ruler 6, also known as Muyal Jol (Martin and Grube 2008:196) (Figure 5). In the study by Christian Prager and Elisabeth Wagner (2017), the name of this ruler is identified on the sculptured step CPN 3033 from Structure 11-sub and contains Chan Ahk, and he is associated with the date 9.3.0.0.0 on Stela 28 (January 30, A.D. 495) (Figure 5c). However, it is important to note that Chan Ahk represents only the second part of his name. The known spellings of the primary element of the name contain the character T1049, which is probably combined with an icon of a drop or a cloud, whose exact reading has not yet been established (Figure 5).

|

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d | e |

|

Figure 5. Variants of the proper name of Copan, Ruler 6: (a, b) Copan, Stela 64: C1, photograph by Seiichi Nakamura, drawing by Christian M. Prager; (c) Copan, CPN 3033: M1-N1, drawing by Christian M. Prager; (d) Copan, Stela 28: Ap4-Bp4, drawing by Elisabeth Wagner; (e) Copan, Altar Q, drawing by Annie Hunter, cited from Maudslay 1889-1902, Vol. 1, Plate 92, public domain. |

||||

The proper name of Ruler 6 in inscription CPN 3033 features a sign that closely resembles the grapheme T1049, UH, but additionally has two rows of drops in front of the nasal opening (Figure 5c). Whether these rows of drops are a variant of the “ik'-breath scroll” part of grapheme T1049bh, whether they represent a separate sign preceding grapheme T1049br, or whether the two graphemes in combination constitute a new and hitherto not understood sign has not yet been clarified. This gives rise to possible variants such as Uh Chan Ahk, ? Uh Chan Ahk, or ?. On Stela 28, all components of the name are merged into a single block resulting in an icon representing a composite creature, with the sign for AHK indicated only by the reptilian scales on the chin of that creature (Figure 5d). The drops on CPN 3033 correspond to the flanged edge forming the outline of the skull forehead, while possible internal elements of the forehead area have been lost due to erosion. On Altar Q, the name also appears in an abbreviated spelling with only two recognizable elements (Figure 5e): a sign similar to the MUY(AL) grapheme T632st and a later one in the form of a human skull. This arrangement led to the interpretation of the name as Muyal Jol (Martin and Grube 2008:196). However, as the mouth part of the skull is damaged, it is not possible to determine whether a lower jaw existed or whether another sign was engraved at this point. It is conceivable that CPN 3033 represents an iconography in which the "ik'-breath" depicted in the T1049bh spelling should be interpreted specifically as "moist and steaming breath" due to the drops. This could explain the later alternative spellings using the symbol/sign T632 for clouds, MUYAL, on Altar Q or Stela 28, possibly the upper part of logogram T44 (variants T44bt/do/dt) for vapor or mist (TOK). In this case, the proper name of Ruler 6 would be understood as Uh Chan Ahk. Since the reverse of Stela 64 is missing the T1049 name component, it is reasonable to assume that it was originally located at the bottom of the monument, on the front.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d | e | f |

|

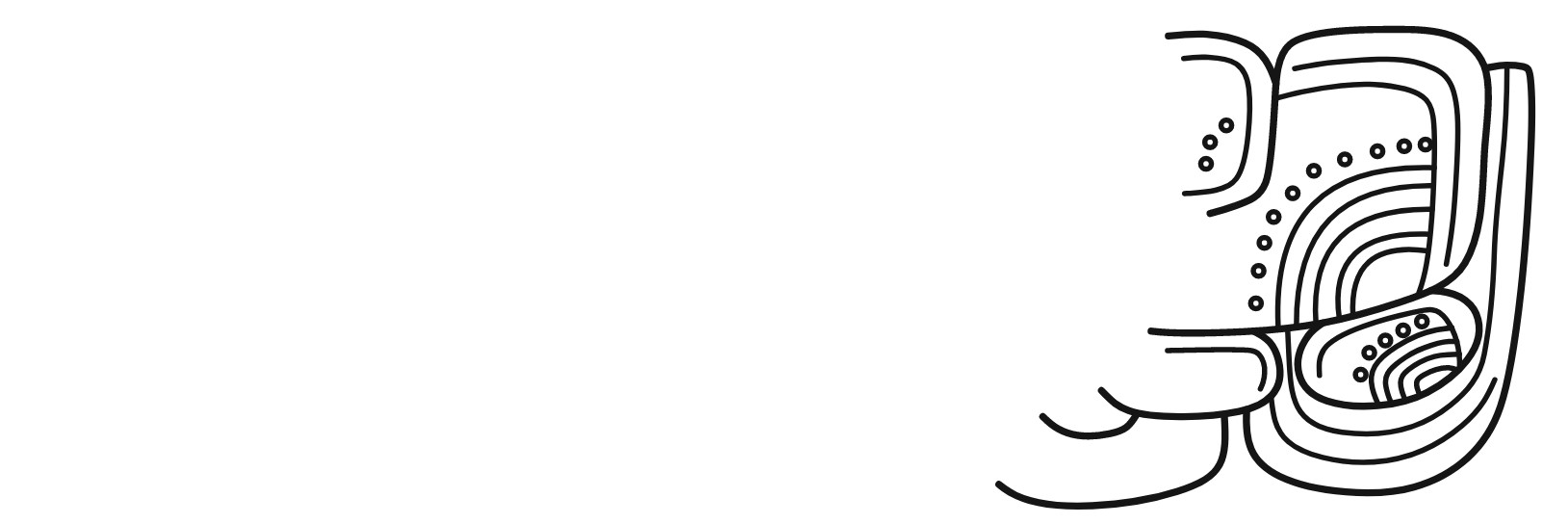

Figure 6. Evidence of the toponym Chihcha': (a) Copan, Stela 64: D2, photograph by Seiichi Nakamura, 2024, all rights reserved; (b) Copan, Stela 64: D2, drawing by Christian M. Prager, 2024; (c) Tikal, Stela 31: C7, drawing by David Stuart; (d) PNK, Region of La Florida (after Hellmuth 1987:167), drawing by David Stuart; (e) Copan, Stela 4: A5a, drawing by David Stuart; (f) PNK, K1882, detail, photograph by Justin Kerr (Images c-d after Stuart 2014:Figure 2a-d). |

|||||

The text on Stela 64 continues in the destroyed hieroglyph C2 and mentions the hieroglyph 671st:316st:116st CHIH-CHA'-TUUN-ni chih cha’ tuun "stone for grinding maguey" in the partially damaged block D2. This toponym, consisting of the signs for chih "maguey", cha' "stone for grinding," and tuun "stone," has been linguistically deciphered by David Stuart (2014, 2018). In the literature, the toponym "stone for grinding maguey", documented in about twenty texts from the Maya lowlands, is also recorded as "bent-cauac", "chi-throne place" or "chi-witz" (Grube 2004:127; Tokovinine 2013:59, 78; Database) (Figure 6). Chihcha' represents an enigmatic place name that at Copán has so far only been identified on Stela I, erected during the reign of K'ahk' Uti' Witz' Kawiil around 9.13.0.0.0, as well as on Stela 4, erected by Waxaklajuun Ubaah K'awiil around 9.14.15.0.0 (Tokovinine 2013, Database, #1338, #1311) (Figure 6e). The inscriptions on these two monuments refer in their narrative to a calendrical ritual that was celebrated before the founding of the Copan dynasty, on the period ending 8.6.0.0.0. This ceremony, which dates back to A.D. 159, the time before the inscription attesting to the rise of the kingdoms, was associated with the historical and legendary figure of Yop Huun and served later kings as a model for their own rituals by referring to it in their narratives. The name Yop Huun is an epigraphic attempt to approximate the original pronunciation of this still undeciphered proper name. In previous research literature it is also known under the aliases of "Foliated Ajaw", "Capped-Ahau", "Decorated Ajaw" or "Leaf Ajaw" (Schele 1982:80; Martin and Grube 2008:193; Braswell et al. 2004). Late Classic kings' inscriptions at Copán refer to this Formative pre-dynastic event and its legendary protagonist Yop Huun in their ritual accounts in the context of the Late Classic Period Endings 9.13.0.0.0 and 9.14.5.0.0. Given the wide temporal and spatial distribution of this name and the associated toponym Chihcha' in Maya Lowland inscriptions, Yop Huun or persons bearing this designation as a title must have played a similar formative role for the institution of kingship as Charlemagne once did for the founding and legitimization of European royal houses. It became the ideal model of royal power and Christian rule, emulated by many later European rulers.

The identity of the toponym Chihcha' remains a mystery to this day. It appears to be a site that has not yet been clearly identified; sites such as El Mirador, Nakbe, or another important Early Classic site in the central lowlands are under discussion (Grube 2004:130-131; Stone and Zender 2011:234; Stuart 2014). These sites, and one of their actors, Yop Huun, were of critical importance to kings during the Early and Late Classic periods, serving as the centerpiece of an origin narrative that was later referenced by rulers such as the dynastic founders of Tikal and Calakmul. The discovery of Stela 64 represents the first evidence that the Early Classic kings of Copan also sought a connection to this legendary site. Thus, like other early kingdoms, they integrated the narrative of the origin of kingship in the Maya lowlands into their historical records, legitimizing their own rule through references to these early histories.

The next hieroglyphic block, C3, is unfortunately destroyed, so the actual narrative continues in block D3 (Figure 7). In this block is a partially legible hieroglyph, [???.542st]:23st, which can be reconstructed by comparative analysis with Copán Stelae 64 and 34 as *che-e-na, read che'een. Nikolai Grube identified this hieroglyph as a particle with the meaning "thus it is said" (Grube 1998). This citation particle usually ends direct speech in inscriptions and is closely associated at Copán with the proper name of Ruler 4, also known as K'altuun Hix (Stuart 2004:231), whose name is mentioned in the partially destroyed hieroglyphic block C4. The particle che'een preceding the name of Ruler 4 indicates that Ruler 4 was speaking at the time and names his successor, Ruler 6, mentioned above in positions C1-D1 of the text, as his ancestor. Remains of K'altuun Hix's proper name are found in position C4 and show the characteristic sign T713 K'AL, as well as the remains of an ear belonging to the sign T524 HIX; the other parts of his name are unfortunately illegible (Figure 7).

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d |

| Figure 7. Variants of the proper name of Copan, Ruler 4: (a, b) Copan, Stela 64: (a) Photograph by Seiichi Nakamura, 2024; (b) Drawing by Christian M. Prager); (c) Copan, Stela 34. Drawing by Linda Schele, all rights reserved; (d) Copan, Papagayo Stone, front. Drawing by Linda Schele, inking by Mark van Stone, all rights reserved. |

|||

An epithet mentioned on Stela 64, composed of the sign 282md NUUN and the undeciphered sign T1735, showing a male face with a dotted circle as a mouth, is of great importance for the historical classification of Ruler 4 in the history of the Maya Lowlands (Figure 8a, b). Stephen Houston identified this expression as the toponymic title of origin of the rulers of the dynasty of Río Azul, an important Early Classic site in central Petén (Houston 1986:5-7). Nikolai Grube, Linda Schele, and Federico Fahsen have already noted these historical links between the early dynasties of Copán and Río Azúl based on the citation of this title on Stela 20 (Grube et al. 1995:3; Schele 1990:4) (Figure 8c). Although no recognizable name of a Copán ruler is preserved on this much-destroyed stela, the same date is found as on Stela 64, which would lead to the conclusion that the name K'altuun Hix was once inscribed here as well. Thus, the discovery of Stela 64 demonstrates that Ruler 4 was the bearer of this title and, therefore, was closely linked to the royal house of Río Azul, and perhaps even had family connections there. The latter is also supported by the nominal phrase of Ruler 4 on the Papagayo Stone, which contains the epithet Huxhaabte', which is also associated with Río Azul and other cities such as Los Alacranes, La Honradez, and Xultun in northeastern Petén (cf. Beliaev 2000:66, 95-96; Krempel and Matteo 2012:164; Tokovinine 2008:95-96; 2013:17-18; Gronemeyer 2016:106) (Figure 8c).

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d |

|

Figure 8. Mentions of the Río Azúl dynastic title in texts at Copan: (a, b) Copán, Stela 64: (a) Photograph by Seiichi Nakamura, 2024; Drawing by Christian M. Prager, 2024; (b) Río Azul emblem glyph on Kerr 1446, drawing by Stephen Houston (1986:6) (c) Copán, Stela 20. Drawing of the upper fragment by Linda Schele, drawing of the lower fragment by Sylvanus Morley (image citation after Morley 1920:72, Figure 10); (d) Papagayo Stone, front, detail. Drawing by Linda Schele, inking by Mark van Stone, all rights reserved. |

|||

Until the future discovery of the missing lower part of Stela 64, it is unclear what other information the monument contained. At least on the left narrow side there was also an inscription, as can be surmised from the remains of the outlines of individual hieroglyphic blocks on the lower end of the Stela 64 fragment. However, this is also found on other Copan stelae and is therefore not unusual. Drilled rows of dots, which could be part of the sign T32 K'UH, are still preserved on the right segment of the latter. The rest of the inscription has survived too little to identify other signs. In addition, a relief border framing the inscription is partially preserved on the left (Figure 4b).

Summary and Outlook

The discovery of Stela 64 represents a significant advance in the study of the Early Classic Copán Maya dynasty. The stela, dated to around A.D. 495, provides valuable new data on Rulers 4 and 6, as well as on Ruler 4's dynastic connections to Río Azul and the enigmatic site of Chihcha', which has yet to be located. Analysis reveals that Stela 64 not only contains important calendrical information, but also suggests a deeper historical and cultural connection between Copán and other prominent Early Classic sites in the lowlands. The reuse of the stela as building material in later structures reflects the widespread practice of spolia use at Copán, which has both practical and symbolic implications. This practice demonstrates how earlier monuments and their inscriptions remained significant to later generations, underscoring dynastic continuity and connection to ancestors. Overall, the discovery of Stela 64 expands the understanding of Early Classic Maya history and offers new insights into dynastic and cultural developments at Copán and beyond. Hopefully, other parts of this important monument will come to light during current research and help complete our picture of Copán's early history.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this article thank the Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia (IHAH) and its manager Dr. Rolando Canizales for allowing us to study Stela 64 and publish this article. We also thank Alejandro Garay and Dimitris Markianos for their epigraphic comments regarding Copán's relation to Río Azul, and to Masahiro Ogawa for his collaboration in the photographic record of Stela 64, as well as to the IHAH staff in Copán Ruinas for the elaboration of the press release on the finding of Stela 64 in March 2024. The archaeological investigations at Copan by PROARCO II team was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18H03586, JP22H04928, JP23K17276, and Honduras-Japan Non-Project Counterpart Fund.

References

Agurcia Fasquelle, Ricardo

2007 Copán: Reino Del Sol - Kingdom of the Sun. Transamérica, Tegucigalpa.

Agurcia Fasquelle, Ricardo, and Barbara W. Fash

2005 The Evolution of Structure 10l-16, Heart of the Copán Acropolis. In: Copán: The History of an Ancient Maya Kingdom, edited by E. Wyllys Andrews and William L. Fash, pp. 201–37. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe.

Agurcia Fasquelle, Ricardo, Donna K. Stone, and Jorge Ramos

1996 Tierra, tiestos, piedras, estratigrafía y escultura: Investigaciones en la Estructura 10L-16 de Copán. In: Visión del pasado maya: Proyecto Arqueológico Acropolis de Copan, edited by Ricardo Agurcia Fasquelle and William L. Fash, pp. 185–201. Asociación Copán Publicación No. 2. Asociación Copán, San Pedro Sula.

Andrews, E. Wyllys, and Barbara W. Fash

1992 Continuity and Change in a Royal Maya Residential Complex at Copan. Ancient Mesoamerica 3:63–88. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536100002315.

Baudez, Claude F. (editor)

1983 Introducción a la arqueología de Copán, Honduras, Vol. 1. Proyecto Arqueológico Copán and Secretaría de Estado en el Despacho de Cultura y Turismo, Tegucigalpa.

Baudez, Claude F., and Berthold Riese

1990 Maya Sculpture of Copan. Manuscript. Series 73, No. 381. Microfilm Collection of Manuscripts on Cultural Anthropology, Chicago.

Beliaev, Dmitri

2000 Wuk Tsuk and Oxlahun Tsuk: Naranjo and Tikal in the Late Classic. In: The Sacred and the Profane: Architecture and Identity in the Maya Lowlands, edited by Pierre R. Colas, Kai Delvendahl, Markus Kuhnert, and Annette Schubart, pp. 63–81. Acta Mesoamericana No. 10. Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

Bell, Ellen E., Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer

2004 Understanding Early Classic Copan: A Classic Maya Center and Its Investigation. In: Understanding Early Classic Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer, pp. 1–14. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Braswell, Geoffrey E., Christian M. Prager, Cassandra R. Bill, Sonja A. Schwake, and Jennifer B. Braswell

2004 The Rise of Secondary States in the Southeastern Periphery of the Maya World: A Report on Recent Archaeological and Epigraphic Research at Pusilha, Belize. Ancient Mesoamerica 15: 219–233.

Eaton, Tim

2000 Plundering the Past: Roman Stonework in Medieval Britain. Tempus, Stroud.

Esch, Arnold

1969 Spolien: Zur Wiederverwendung antiker Baustücke und Skulpturen im mittelalterlichen Italien. Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 51:1–64.

Fash, Barbara W.

2004 Early Classic Sculptural Development at Copan. In: Understanding Early Classic Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer, pp. 249–264. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Fash, William L.

1988 A New Look at Maya Statecraft from Copan, Honduras. Antiquity 62 (234):157–169.

2001 Scribes, Warriors and Kings: The City of Copan and the Ancient Maya. Revised Edition. Thames & Hudson, London and New York.

Gordon, George B.

1902 The Hieroglyphic Stairway, Ruins of Copan: Report on Explorations by the Museum. Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Vol. 1, No. 6. Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Gronemeyer, Sven

2016 The Linguistics of Toponymy in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. In: Places of Power and Memory in Mesoamerica’s Past and Present: How Sites, Toponyms and Landscapes Shape History and Remembrance, edited by Daniel Graña-Behrens, pp. 85–122. Estudios Indiana No. 9. Gebr. Mann, Berlin.

Grube, Nikolai

1998 Speaking Through Stones: A Quotative Particle in Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions. In: 50 años de estudios americanistas en la Universidad de Bonn: nuevas contribuciones a la arqueología, etnohistoria, etnolingüística y etnografía de las Américas = 50 Years Americanist Studies at the University of Bonn: New Contributions to the Archaeology, Ethnohistory, Ethnolinguistics, and Ethnography of the Americas, edited by Sabine Dedenbach-Salazar Sáenz, Carmen Arellano Hoffmann, Eva König, and Heiko Prümers, pp. 543–558. Bonner Amerikanistische Studien No. 30. Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

2004 “El origen de la dinastía Kaan. In: Los cautivos de Dzibanché, edited by Enrique Nalda, pp. 117–131. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City.

Grube, Nikolai, Linda Schele, and Federico Fahsen

1995 Tikal-Copan Connection: Evidence from External Relations. Copán Note 121. Copán Acropolis Archaeological Project and Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia, Austin.

Hellmuth, Nicholas M.

1987 Monster und Menschen in der Maya-Kunst: Eine Ikonographie der alten Religionen Mexikos und Guatemalas. Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, Graz.

Houston, Stephen D.

1986 Problematic Emblem Glyphs: Examples from Altar de Sacrificios, El Chorro, Río Azul, and Xultun. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing No. 3. Center for Maya Research, Washington, DC.

Iglesia, Martin de la, Franziska Diehr, Uwe Sikora, Sven Gronemeyer, Maximilian Behnert-Brodhun, Christian M. Prager, and Nikolai Grube

2021 The Code of Maya Kings and Queens: Encoding and Markup of Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative Issue 14. https://journals.openedition.org/jtei/3336.

Kinney, Dale

2019 The Concept of Spolia. In: A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe, edited by Conrad Rudolph, pp. 331-356. Second edition. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford.

Landa, Diego de

1941 [1566] Landa´s Relación de Las Cosas de Yucatan: A Translation. Translated by Alfred M. Tozzer. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology No. 18. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube

2008 Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. Second edition. Thames & Hudson, London and New York.

Martin, Simon, and Joel Skidmore

2012 Exploring the 584286 Correlation between the Maya and European Calendars. The PARI Journal 13(2):3–16.

Morley, Sylvanus G.

1920 The Inscriptions at Copan. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication No. 219. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC.

Nakamura, Seiichi

2024 Nuevos datos e interpretaciones sobre la historia dinástica del período Clásico Temprano en Copán, Honduras. Paper presented at 37 Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, Guatemala City.

Nakamura, Seiichi, Melvin Fuentes, Masahiro Ogawa, and Carlos Carbajal

2021 PROARCO II (Proyecto Arqueológico Copán, Segunda Fase): Objetivos, Justificación y Resultados Preliminares. Kanazawa Cultural Resource Studies No. 28. Kanazawa University, Kanazawa.

Nielsen, Jesper

2013 Saints and Spolia: Crisis and Resilience in the Art and Architecture of Early Colonial Yucatan. Paper presented at 18 European Maya Conference: Post-Apocalypto: Crisis and Resilience in the Maya World, Brussels.

2020 The Memory of Stones: Ancient Maya Spolia in the Architecture of Early Colonial Yucatan. PARI Journal 20 (3):1–15.

Prager, Christian M., and Sven Gronemeyer

2018 Neue Ergebnisse in der Erforschung der Graphemik und Graphetik des Klassischen Maya. In: Ägyptologische “Binsen”-Weisheiten III: Formen und Funktionen von Zeichenliste und Paläographie, edited by Svenja A. Gülden, Kyra V. J. van der Moezel, and Ursula Verhoeven-van Elsbergen, pp. 135–181. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Abhandlungen der Geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse No. 15. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart.

Prager, Christian M., and Elisabeth Wagner

2017 Historical Implications of the Early Classic Hieroglyphic Text CPN 3033 on the Sculptured Step of Structure 10L 11-Sub-12 at Copan. Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya, Research Note 7. Electronic document, https://classicmayan.org/portal/doc/166.

Ramos Gomez, Jorge Humberto

2006 The Iconography of Temple 16: Yax Pasaj and the Evocation of a ‘Foreign’ Identity at Copan. Ph.D. dissertation. University of California, Riverside.

Schele, Linda

1982 Maya Glyphs: The Verbs. University of Texas Press, Austin.

1987 A Possible Death Date for Smoke-Imix-God K. Copán Note 26. Copán Acropolis Archaeological Project and Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia, Austin.

1990 The Early Classic Dynastic History of Copán: Interim Report 1989. Copán Note 70. Copán Acropolis Archaeological Project and Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia, Austin.

Sedat, David W., and Robert J. Sharer

1994 The Xukpi Stone: A Newly Discovered Early Classic Inscription from the Copán Acropolis, Part I: The Archaeology. Copán Note 113. Copán Acropolis Archaeological Project and Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia, Austin.

Stone, Andrea, and Marc Zender

2011 Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. Thames & Hudson, London and New York.

Strømsvik, Gustav

1941 Substela Caches and Stela Foundations at Copan and Quirigua. Contributions to American Anthropology and History, Vol. 7, No. 37:63–96. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication No. 528. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC.

Stuart, David

2004 The Beginnings of the Copan Dynasty: A Review of the Hieroglyphic and Historical Evidence. In: Understanding Early Classic Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer, pp. 215–247. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

2014 A Possible Sign for Metate. Electronic document, http://decipherment.wordpress.com/2014/02/04/a-possible-sign-for-metate/.

2018 An Update on CHA’, ‘Metate’. Electronic document, https://decipherment.wordpress.com/2018/07/27/an-update-on-cha-metate/.

Thompson, J. Eric S.

1962 A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Tokovinine, Alexandre

2013 Place and Identity in Classic Maya Narratives. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology No. 37. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

Wagner, Elisabeth

2006 White Earth Bundles: The Symbolic Sealing and Burial of Buildings among the Classic Maya. In: Jaws of the Underworld: Life, Death, and Rebirth among the Ancient Maya, edited by Pierre R. Colas, Geneviève Le Fort, and Bodil L. Persson, pp. 55–69. Acta Mesoamericana No. 16. Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

2016 Edificios como reliquias ancestrales: Un caso de Copán, Honduras. Paper presented at I Congreso Internacional de Arquitectura e Iconografía Precolumbina, Valencia.

Webster, David

1989 The House of the Bacabs: Its Social Context. In: The House of the Bacabs, Copán, Honduras, edited by David Webster, pp. 5–40. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology No. 29. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

Zimmermann, Günter

1956 Die Hieroglyphen der Maya-Handschriften. Vol. 62. Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiet der Auslandskunde. Reihe B, Völkerkunde, Kunstgeschichte und Sprachen. Cram, de Gruyter & Co., Hamburg.

- All illustrations by Christian Prager are available under the Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 license.

- As part of our work on a new catalog of Maya signs and their graphs, we have been evaluating and revising Thompson’s Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs (1962). We are critically scrutinizing his system with the help of his original grey cards and supplementing it with signs that were not included in Thompson’s original catalog. Despite its known shortcomings and incompleteness, his catalog is still regarded as the standard work for Maya epigraphers, which is why we adopt Thompson’s nomenclature while removing misclassifications and duplicates, merging graph variants under a common nomenclature, and adding new signs or allographs to the sign index in sequence, starting with the number T1500. Allographs are also further organized with the help of newly defined classification and systematization criteria, which we described in detail in Prager and Gronemeyer (2018).In the transliteration of Maya hieroglyphic script, bold typeface is employed, with uppercase letters representing LOGOGRAPHIC signs and lowercase letters denoting syllabic signs. To accurately describe the spatial arrangement of glyphs within a hieroglyphic block, the notation system established by Günter Zimmermann (1956) and Eric Thompson (1962) is utilized. This convention, also adopted by the Project Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan, specifies that adjacent glyphs are separated by a period (.), vertically stacked glyphs by a colon (:), and distinct segments comprising groups of glyphs within the hieroglyphic block are enclosed in square brackets [ ]. When a glyph is embedded within another, it is indicated by a degree symbol (°) (cf. Zimmermann 1956), whereas the fusion of two glyphs is denoted by a plus sign (+) (cf. Iglesia et al. 2021). T-numbers in the transliterations denote undeciphered signs and reference Thompson's Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs.