und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

The White Maidens of Maya Mythology

Research Note 32

February 13, 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.25.rn032.en

Nikolai Grube (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Introduction

Classic Maya mythology remains an enigmatic and largely uncharted domain. While a few well-established points of reference provide some orientation, researchers still navigate through largely unknown territory, as the metaphorical maps that once guided understanding have been lost or rendered indecipherable over time. Despite significant advances in recent years, our insights into Maya worldview and thought remain fragmentary and selective.

In such a context, caution is often warranted; it is prudent to limit the scope of exploration to avoid straying too far from familiar ground. This approach underpins the strategy of this brief paper, in which I propose the existence of a "white maiden" figure in Maya mythology. This figure, I argue, personified both the number two and the color white. Furthermore, she appears to have been linked to the seventh "Lord of the Night" and associated with the House of the North, the palace of the old “Lord of the Underworld” God L.

While many of the individual observations presented here have been made in prior studies, my aim is to synthesize these elements to suggest the presence of a group of previously unrecognized female deities within the Maya pantheon.

The head variant for white

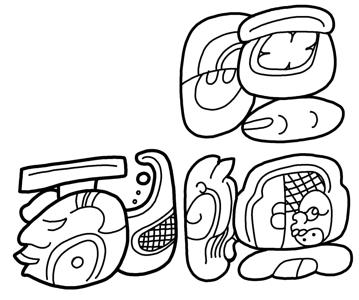

The logogram represented by Graph 58st [1] representing the color "white" ( sak ) was first identified by Eduard Seler (1902–23, I: 410–411) (Figure 1) [2] . Seler’s identification was based on information from Landa's Relación and the presence of color terms in month names. The term sak for "white" derives from the Proto-Mayan root * saq (Kaufman 2003: 200–221).

|

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d | e |

|

|

|

|

|

| f | g | h | i | |

|

Figure 1. The Logogram SAK: a) Early Classic jade mask (Houston and Inomata 2003: Figure 2.3); b) Calakmul Stela 89; c) Panel of unknown provenance (Mayer 1995: Cat. No. 23); d) Caracol, Ballcourt Marker 4; e) Chichen Itza, Monjas, Lintel 3; f) Ceramic vessel of unknown provenance (Boot 2003: 8, Fig. 5); g) Naj Tunich, Drawing 88; h) Ceramic plate of unknown provenance (from Zender 2000: 1044, Fig. 10b); i) Quirigua, Stela E. |

||||

The reading of the logogram as SAK is further supported by occasional phonetic complements, such as ka at Naj Tunich (Figure 1g) and ki on a ceramic plate (Figure 1h). The disharmonic ki syllabogram may suggest the presence of a long or complex vowel, though this cannot be linguistically justified, as the word for "white" consistently exhibits a short vowel across all Mayan languages (Houston et al. 2009: 32; Zender 2000: 1044).

In addition to these examples, there is a possible fully syllabic spellings of sak as sa-ku on Quiriguá Stela E (Figure 1i). Notably, the sa sign 278bt used in these spellings may have originated from the SAK logogram, as it appears to represent the upper portion of the Early Classic variant of the sign, such as in Figure 1f (see also Houston et al. 2009: 32). Another interpretation of this rare spelling of the month name Sak is that it simply represents an abbreviated form of the term SAK SIHOOM , where the SAK sign is reduced to the top of the sign.

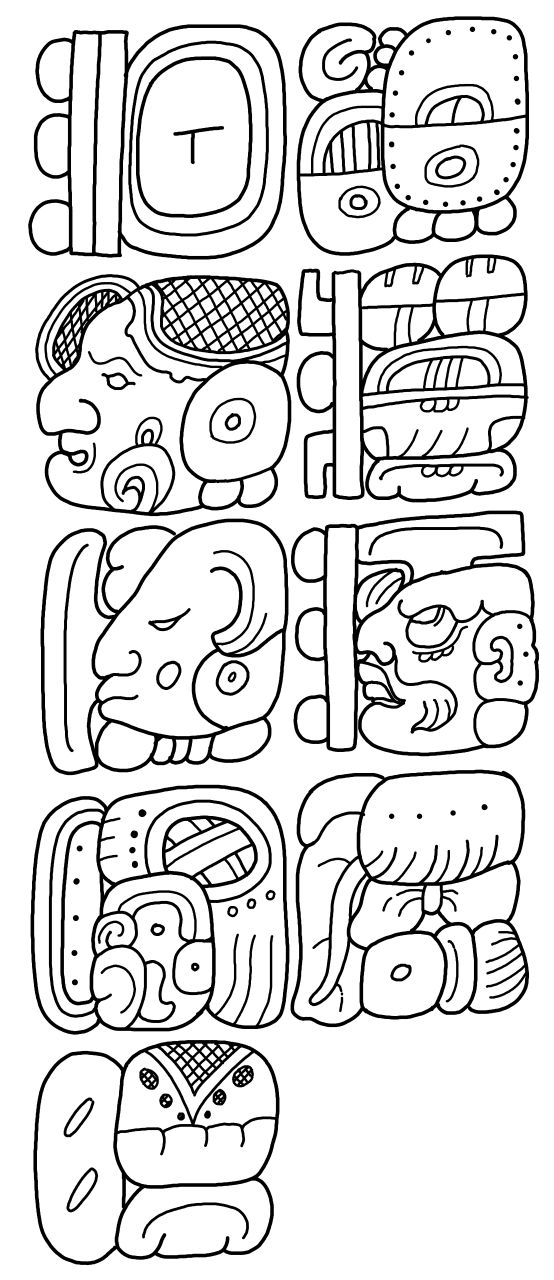

The existence of a head variant for the logogram SAK "white" has largely gone unnoticed. This variant is attested in at least four distinct contexts. The first example is found in the Initial Series date on Copan Stela E, a source of considerable debate among epigraphers due to its atypical representations of the numbers (cf. Schele 1987, 1989). In this instance, the month associated with the Long Count is Sak, but the sak element is rendered using a head variant classified as 1086vc, with its upper portion forming a stylized human fist (Figure 2a).

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d |

| Figure 2. The head variant for SAK: a) The head variant in the color month name Sak, Copan, Stela E; b) The head variant in the glyph u-li SAK-HA’ for a variant of atole, Kerr 1670; c) The head variant in the sequence ta-SAK ju-yu CH’ICH’, Kerr 8777; d) The head variant in the toponym Sak Nikte’, La Corona, Altar 1. | |||

Another occurrence of this head variant is present on a ceramic bowl originating from the La Florida/Namaan region [3] (Kerr 1670) (Figure 2b). In this context, the contents of the vessel u-li SAK-HA' are described using two distinct terms for atole : the word ul (Kaufman and Norman 1984: 135) and the phrase sak ha , meaning "a beverage made from corn dough" (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 709) [4] . For the logogram SAK , the same head variant observed on Copan Stela E is utilized, alongside the standard SAK logogram (the entire compound is cataloged as Graph 1086vs in our modified Thompson Catalog).

Another example of the personified SAK sign (Graph 1086vc) appears in the context of a vessel of unknown provenance, which at the end of its dedication text mentions a Waka’/El Peru Ajaw (Kerr 8777; Figure 2c). The text contains a reference to the vessel ( y-uk’ib ) and continues with a description of the contents as ta-SAK-ju-yu CH’ICH’ , ta sak juy ch’ich’ . Christian Prager pointed out that juy in the Ch’olan languages, but also in Yucatecan, Tzeltalan, Q’anjob’alan and Q’ekchi’ is the word for “to stir” and refers specifically to corn gruel such as atole and pinole [5] . A drink labeled sak juy ch’ich’ could therefore represent “white stirred blood”, perhaps a particular beverage based on the metaphor of blood.

Moreover, this combination appears again in the spelling of the toponym Sak Nikte' on La Corona Hieroglyphic Stairway 2, Block V, using Graph 1086va to spell SAK (Figure 2d). These three examples demonstrate that the head variant for "white" is derived from a female head, which in two instances features a fist as an attribute and in two others is paired with the standard SAK logogram.

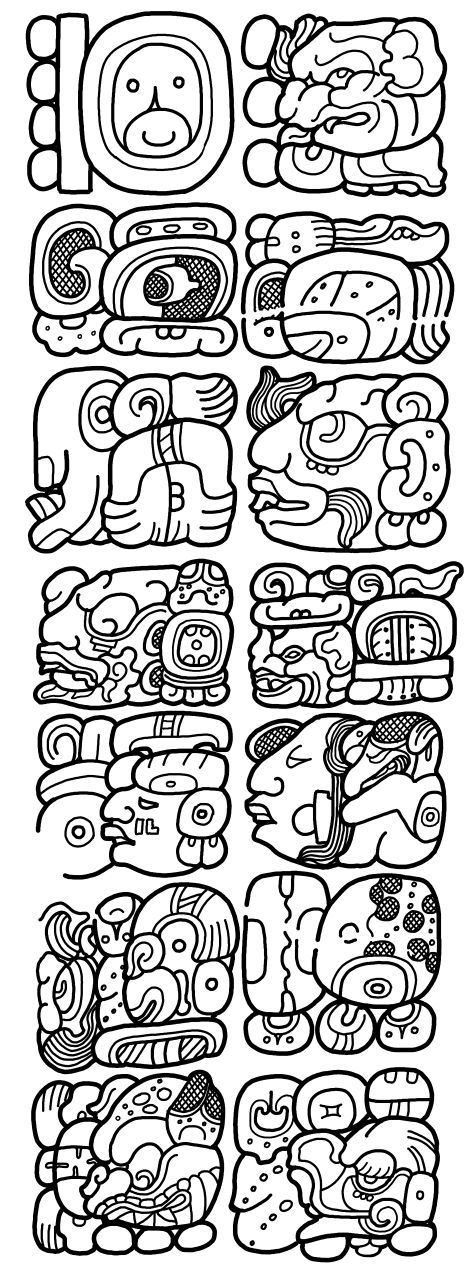

The head variant for the number two

In her discussion of the date on Copan Stela E, Linda Schele observes that "…the head variant of zac is identical to the head variant of the number two, which often has a zac sign appended to it" (Schele 1987: 2). The head variant for the number two was first identified by Enrique Juan Palacios in the context of the discovery of the Tablet of 96 Hieroglyphs and the decipherment of its calendar dates (Palacios 1936) (Figure 3).

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d |

|

|

g |

|

| e | f | ||

| Figure 3. The head variant for the number two: a) The Haab date “2 Zac”, Bonampak, Sculptured Stone 1; b) Hieroglyph 2D of the Lunar Series, Copan, Stela 16; c) The number two, Column of unknown provenance in the Hecelchakan Museum (Mayer 1984: Cat No. 45); d) “2 Haab”, Palenque, Temple XIX, Bench; e) “2 Haab, 2 K’atun”, Palenque, Tablet of the 96 Glyphs; f) “2 Winal”, Piedras Negras, Panel 2; g) Palenque, Temple of the Foliated Cross, Alfardas. | |||

In his analysis of the head variants for numbers, Thompson highlights a distinctive feature: a hand positioned above the head. He further notes that the facial features of the glyph characterize the figure as a youthful individual (Thompson 1950: 131). According to Thompson, the head variant with the hand represents the Classic-period counterpart to God Q of the Codices, whom he interpreted as a deity associated with sacrifice (Thompson 1950: 132). Since Thompson’s work, no other scholars have attempted to interpret the head variant associated with the number two.

Numerous examples of the head variant are attested in the corpus of Maya texts. While the examples from Palenque and Bonampak feature a fist as their defining element, corresponding to 1086vc (Figures 3a, d, e, f), there are also instances where the fist is replaced by the SAK sign (Figure 3b, c), a variant cataloged by us as 1086va, or where it occurs with both the SAK sign and the fist (Figure 3f). The Piedras Negras example shows that the hand sign and the SAK logogram are not interchangeable. In our catalog, this combined form is classified as 1086vs. It is worth noting that the hand sign used in these variants is visually indistinguishable from the logogram 221st OCH "enter", which was deciphered by David Stuart in 1990 (Stuart 1998: 387) (Figure 3g).

The seventh “Lord of the Night”

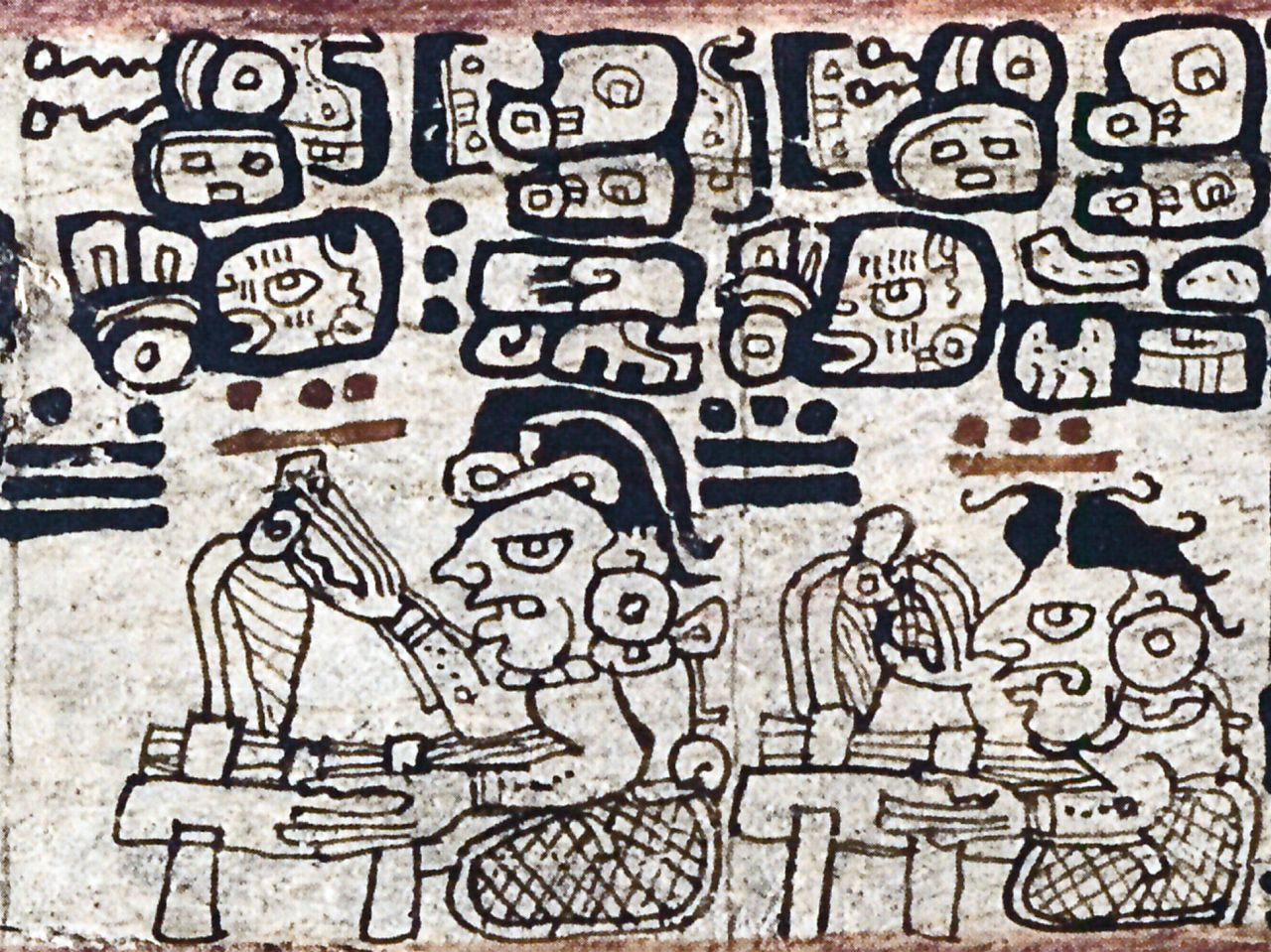

Another context in which the same head variant appears is in the name glyph of the seventh "Lord of the Night". The most notable example is found on Piedras Negras Stela 3 (Figure 4a), where the head with the fist is paired with the NAAH prefix, which also appears in the personification of the number two on Copan Stela 5.

In Copan, Naranjo, Palenque and Quirigua, variants of the seventh "Lord of the Night" feature the NAAH logogram alongside a main sign resembling the standard form 58st of the SAK logogram (Figure 4e, h, i ).

|

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d | e |

|

|

|

|

|

| f | g | h | i | |

| Figure 4. The seventh “Lord of the Night”: a) Piedras Negras, Stela 3; b) Copan, Stela 5; c) Tonina, Monument 127; d) Tortuguero, Monument 6; e) Copan, Stela 2; f) Yaxchilan, Lintel 29; g) Palenque, Palace Tablet; h) Quirigua, Stela D; i) Palenque, Temple XXI, Tablet. | ||||

In some cases, the name of the seventh "Lord of the Night" is abbreviated to the logogram 4vl NAAH , as seen on Tortuguero, Monument 6 (Figure 4d), or rendered as NAAH-la for naahal on Yaxchilan, Lintel 29 (Grofe 2014) (Figure 4f). Additionally, a variant of G7 occurs on the Palace Tablet from Palenque and in other inscriptions, where the name is written with the Graph 4vs, comprising the NAAH sign and a male head (Figure 4b, c, g). This hieroglyph is also identified in Maya hieroglyphic writing as the cardinal direction "north," a function first recognized by Léon de Rosny (1883: 18) (Figure 5). The seventh "Lord of the Night" and the cardinal direction "north" are thus synonymous, both represented by the NAAH sign preceding a head marked by a distinctive round spot on the cheek, which in a few cases can also be absent (Figure 5c, d) and a mark on the back of the head (Grofe 2014: 149–150). As an isolated logogram, this head, Graph 1008st, is read XIB “male.” This particular head, however, often is part of digraphs. When combined with other signs, it can adopt different readings. Together with an infixed WAAJ sign (Graph 1732st) it turns into the logogram for WE’ “eat”, and with a HA’ sign in its mouth (Graph 1070st), the combination reads UCH’ “drink”. The same process seems to take place here when the Graph 4vl representing the NAAH sign is prefixed.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| a | b | c | d | e | f |

| Figure 5. Naahal as “north”: a) Río Azul, Tomb 6; b) Yaxchilan, Stela 11; c) Palenque, Tablet of the Sun; d) Ceramic of unknown provenance (Boot 2003: 8, Fig. 5); e) Dresden 31c; f) Quirigua, Stela K. | |||||

The examples of the seventh "Lord of the Night" from Yaxchilán and Tortuguero indicate that the core of the seventh “Lord of the Night” was read as naah or naahal , which also served as the reading for the glyph representing "north." This interpretation is confirmed by the hieroglyph for "north" in the 819-day count passage on Quiriguá, Stela K, written as NAAH-hi-li (Figure 5f). The combination of the 4vl NAAH sign with the head represents the full form 4vs of the logogram NAAH (Stuart 1998: 367-377).

Support for this reading is found in the sentence a-ALAY-ya i-EL-le NAAH-ja u-MUKNAL-li , alay i el naahaj u muknalil (“and then fire-dedicated is the tomb of”), from La Corona, Panel 2b (Figure 6). In this passage, the full NAAH logogram (Graph 4va) appears within a compound intransitive verb. These substitutions establish beyond doubt that the glyph for "north" was read as naah or naahal and that this term also served as the name of the seventh "Lord of the Night."

|

| Figure 6. La Corona, Panel 2b (Kerr 4677), pG5-pG6: i-EL-le NAAH-ja u-MUKNAL-li, i elnaah u muknalil “and then fire-dedicated is the tomb of”. |

“North” as a house

In Eastern Mayan, Proto-Ch’olan, and Tzeltalan languages, * nah can be reconstructed with the meaning “first” (Kaufman 2003: 279). The Proto-Mayan root * nhaah , featuring a long vowel, appears as the unpossessed form of the word for “house” in most Mayan languages, including Yucatecan and Tzeltalan languages (Kaufman 2003: 947). While this form is absent in contemporary Ch’olan languages, there is no doubt that during the Classic period, the primary meaning of the NAAH logogram was “house,” contrasting with y-otoot (“house of” or “dwelling of”) (Lounsbury 1984: 175; Stuart 1998: 376-380). For the Maya, therefore, the north was conceptualized as a “house.”

|

| Figure 7. Palenque, Temple of the Cross, Tablet, C9-C13: A text passage related to the dedication of a house in the north on 13 Ik’ “end of” Mol. |

This idea may stem from the belief that the north served as a celestial "house" or resting place for heavenly bodies, around which the stars and constellations of the night sky revolved. While today this region is marked by the North Star, during the Classic period, the north was perceived as a dark, empty expanse. In their influential reconstruction of Maya creation mythology, David Freidel, Linda Schele, and Joy Parker highlight that the inscription on the Tablet of the Cross from Palenque explicitly mentions a yotoot xaman , or “house of the north” in the sky, which was dedicated on the day 13 Ik’, end of the month Mol (Freidel, Schele, and Parker 1993: 72) (Figure 7). This passage is particularly noteworthy as it references a house named WAK- T170 -CHAN-na NAAH-la WAXAK-NAAH- T1011 (“six sky house? of the north, eight ?? house”), employing the full NAAH logogram (graph 4vs). Furthermore, the word for "north" in the phrase “house of the north” at the end of the passage is written as xa-MAAN-na , representing xaman (“north”), a term preserved only in Yucatecan languages.

While the three other cardinal directions are each represented by a single term, "north" is unique in having two terms: xaman and naahal . Although this has been known for some time, it has curiously not prompted further detailed investigation. The reading of the hieroglyph xaman is based on a suggestion by Michael Closs (cited in Stuart 1987: 28), which has since been substantiated by considerable additional evidence. This hieroglyph appears consistently throughout the Maya lowlands as a designation for "north” [6] . The term xaman is notably absent from the Codices, which exclusively use naahal to represent "north." In the 819-day count, the expression xaman is also never employed. However, in contexts related to territorial divisions—such as those involving the kalo’mte’ title and the four emblem glyphs on Copan Stela A— xaman is preferred.

This distinction suggests a semantic difference between naahal and xaman : naahal appears to be associated with the celestial north pivot, while xaman , as a cardinal direction or region, likely carried a stronger horizontal or terrestrial connotation. Furthermore, xaman seems to have been a relatively late innovation in Maya writing, with its earliest attested appearance dating to approximately 9.10.0.0.0 [7] (633 CE), a time which is characterized by many changes and innovations in the script (Grube 1990; Houston 2012a).

The white maidens

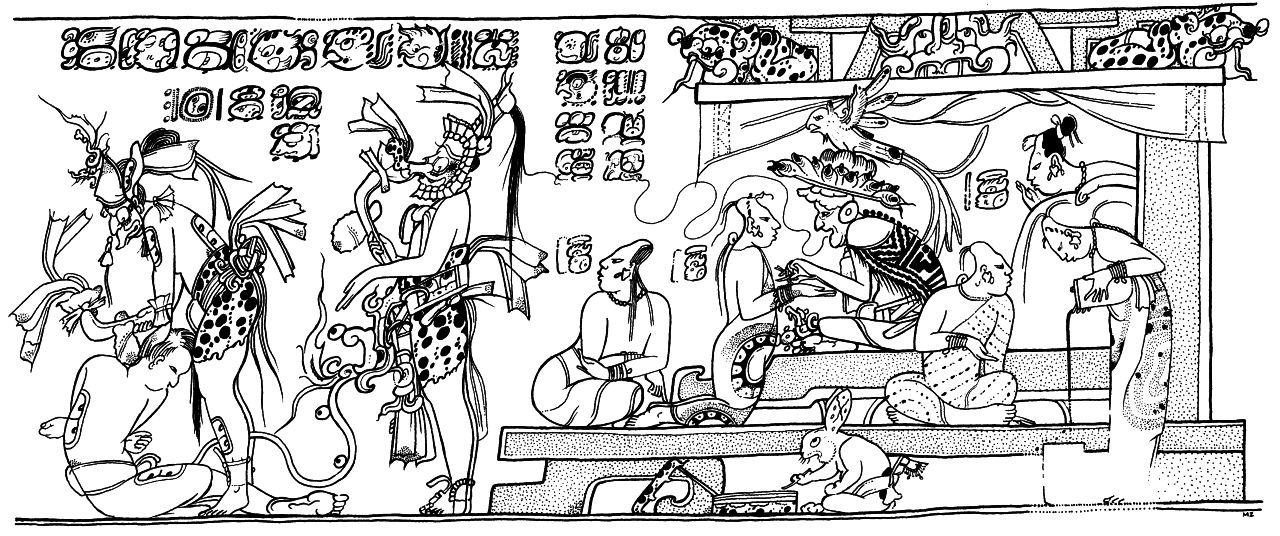

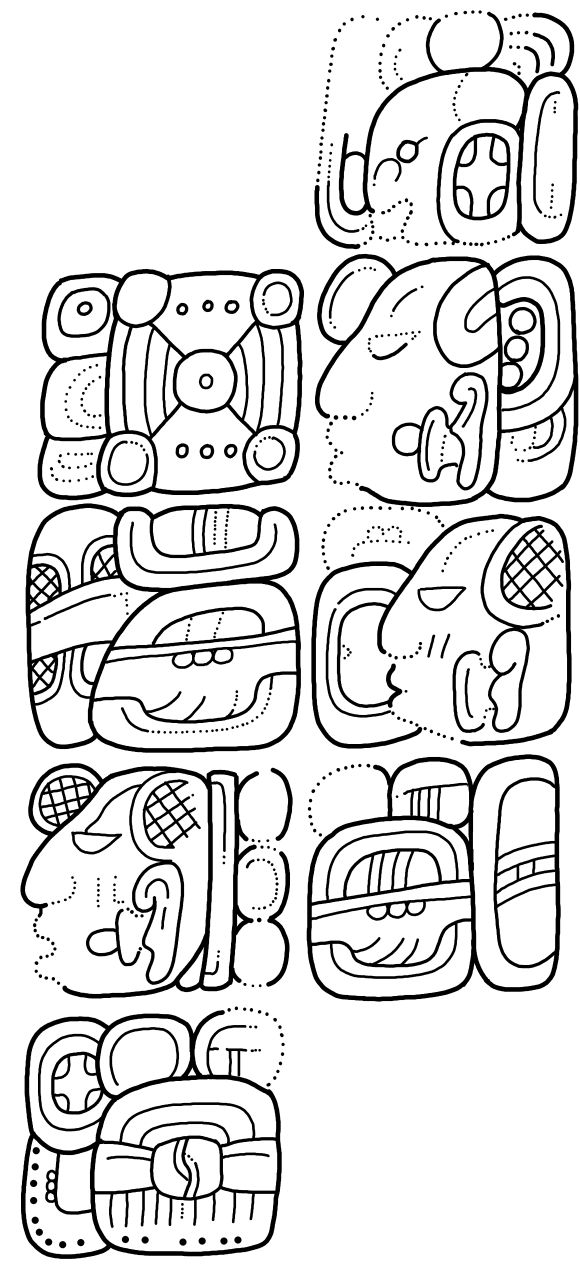

The head variant of Sign 1086, occasionally accompanied by the NAAH prefix, also appears on one of the most renowned Codex-style ceramics, the so-called "Princeton vase" (Kerr 511; Coe 1973: 93; Velásquez García 2009) (Figure 8a). The painting is divided into two scenes. One depicts God L in his underworld palace, accompanied by five young women. One of the women kneels before God L as he either touches or fastens her jade bracelet. An eight-block hieroglyphic text, connected by a fine line to his mouth, indicates that the text is spoken by God L to the lady in front of him. The other maidens converse among themselves, with one pouring cacao from one vessel into another. Three of the women are identified by a hieroglyphic caption. Although partially erased and overpainted, the outlines leave little doubt that the three glyphs are identical, with at least one clearly identifiable as a head topped by a fist and a NAAH superfix (Figure 8b). Preceding this hieroglyph is the number five, likely indicating that these five maidens share the same name. Therefore, there is no doubt that the head variant 1086vc, with the fist, represents the nominal glyph of one or more maidens who, in Maya mythology, serve or attend God L in his palace.

|

|

| Figure 8. The Princeton Vase (Kerr 511) and the name of the White Maiden: a) The Princeton Vase (Drawing by Marc Zender); b) One of the three name glyphs associated with the maidens. | |

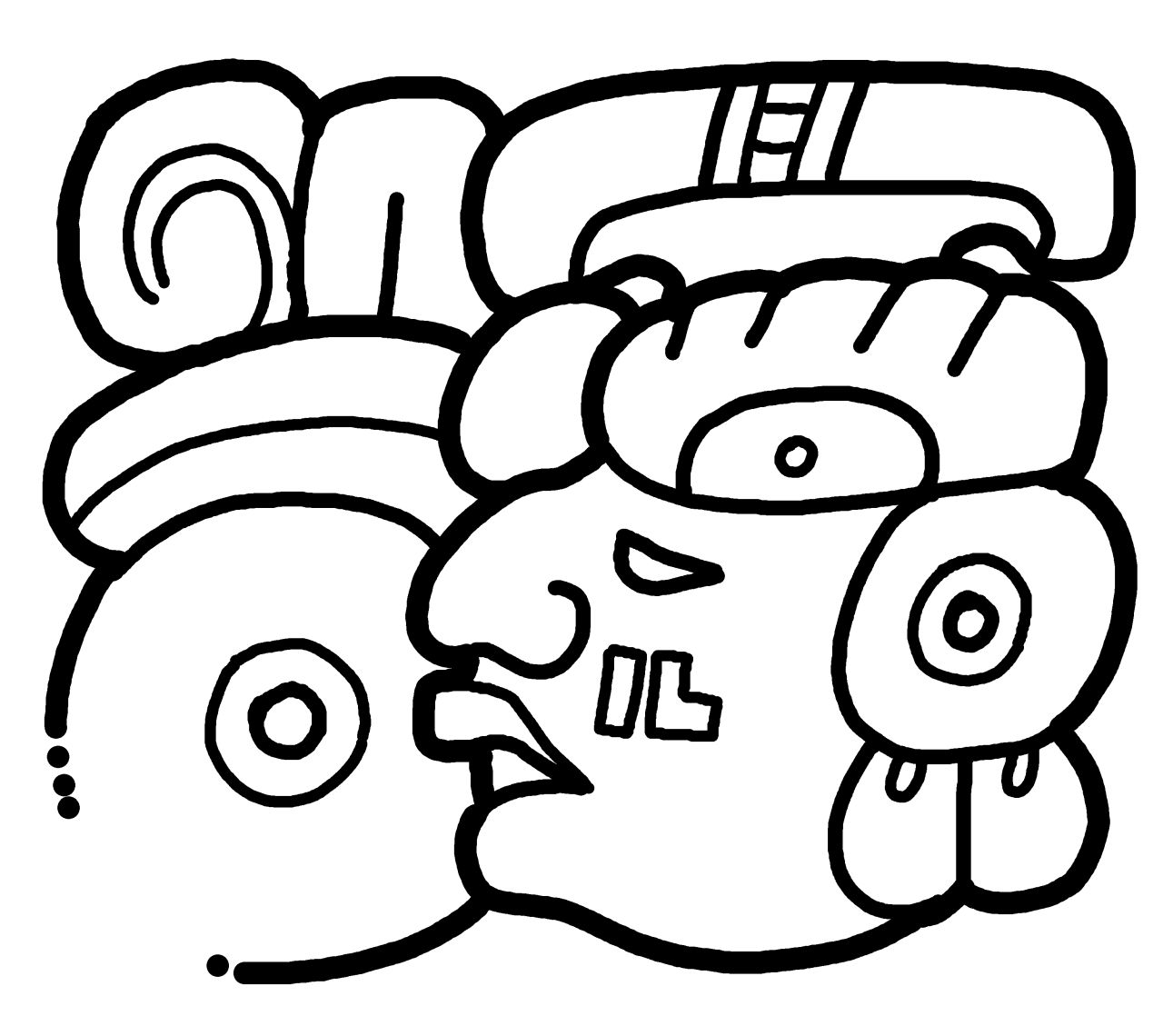

The same maiden is mentioned among the deities of Kan Bahlam on the limestone tablet from Palenque Temple XIV (Figure 9a). The tablet depicts Kan Bahlam dancing in the watery otherworld, with a lady kneeling in front of him, wearing a net overskirt and presenting a figure of K’awiil to the monarch. The text column to the left of the lady references a lunar deity, suggesting that the kneeling figure represents a manifestation of the moon goddess. The text columns on the right connect this mythological event to a specific historical time, marked by the verb och u ch’een ( "entering his otherworld/cave") and the Calendar Round date 9 Ajaw 3 K’ank’in (Figure 9a). This event appears to have occurred in the company of a series of gods, including G1, the Jaguar God of the Underworld, a fire deity, a female deity with a seated Ajaw vulture, and a name based on a head showing all the elements discussed above (Figure 9b). These five deities are identified as u k'uhil , "the deities of” Kan Bahlam, whose name occupies the penultimate position in the inscription. The panel inscription clarifies that the glyph in question represents a female deity distinct from the moon goddess mentioned earlier in the text.

|

|

| a | b |

| Figure 9. The White Maiden in the text of Palenque, Temple XIV, Tablet: a) The text passage C5-D11; b) The name of the White Maiden in C9. | |

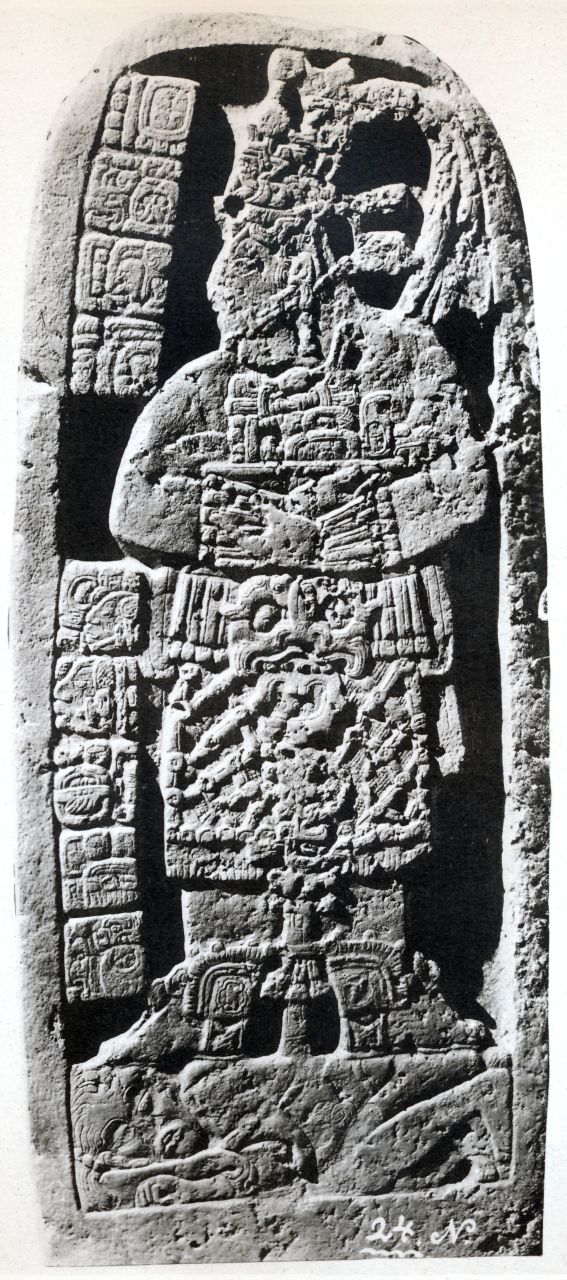

The moon goddess in Maya inscriptions is typically depicted with a female head and a moon sign. Outside of the lunar series, clear references to her are rare. One such instance is found on Naranjo Stela 24, where Lady Wak Jalam Chan is shown manifesting the Moon Goddess in her net overskirt (Figure 10a). According to the text, this manifestation occurs in the shining(?) sky (Figure 10b). It is important to note that the moon goddess is distinct from the White Maiden, who is never associated with lunar symbolism.

|

|

| a | b |

| Figure 10. Lady Wak Jalam Chan representing the Moon Goddess at Naranjo: a) Naranjo, Stela 24, front (Photo by Teobert Maler, from Maler 1908-10, Plate 39); b) Naranjo, Stela 24, right side, text passage E3-D7. | |

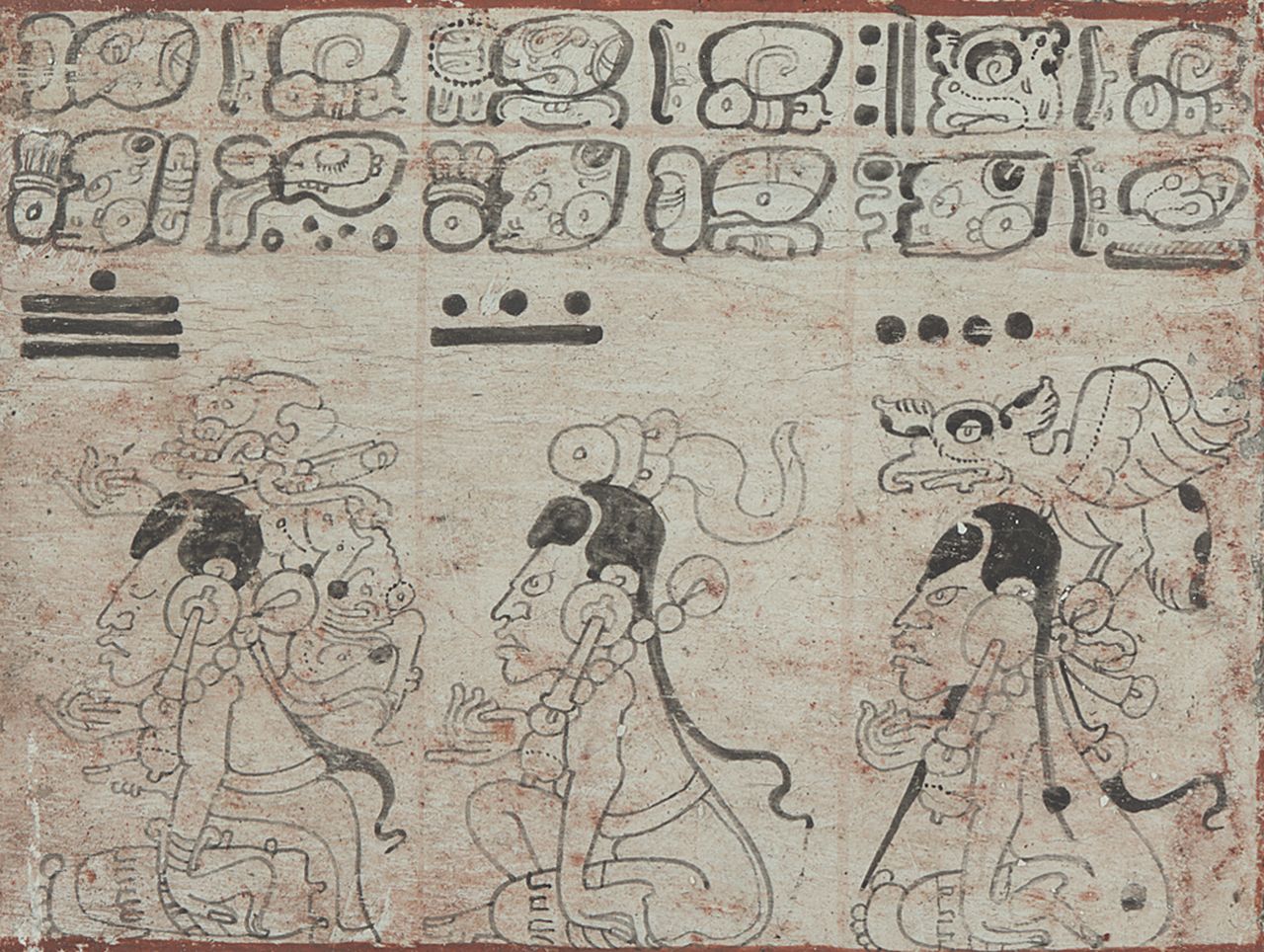

The white maiden, however, survives into the Postclassic period in the form of Goddess I of the Codices (Figure 11). The name of this goddess usually is written SAK IXIK , “white lady” (Figure 11b, c) Often, a ki suffix is added to stress the final / -k / of the word ixik [8] (Wagner 2003) (Figure 11c). Other variants of the name include a different prefix resembling the loop of the Kaban sign (Figure 11d). Several scholars have interpreted this sign as the codex variant of one of Landa’s u signs (Thompson 1950: 86). However, I argue that it is more likely that the prefix represents a curling lock of hair in front of the face, a common attribute in the depiction of female heads in Classic Maya texts and iconography. This suggests that the head should simply be read as IXIK , “woman”.

|

|

|

| a | b | c |

|

|

|

| d | e | f |

|

Figure 11. Sak ixik, “the white lady” in the codices: a) Dresden 18b (digitized image, SLUB Dresden, Public Domain Mark 1.0); b) SAK IXIK, Dresden 18b; c) SAK IXIK-ki, Dresden 18b; d) IXIK, Dresden 18b; e) Madrid 102c (from Anders 1967 ); f) SAK IXIK, Madrid 102c. |

||

Karl Taube has noted that Goddess I, the White Maiden, is distinct from the Moon Goddess (Taube 1992: 64–69). The only image of the Moon Goddess in the Codices where she is depicted carrying a lunar crescent under her arm is found on page 49 of the Dresden Codex, as part of the Venus Tables (Figure 12a). Additionally, her name glyph, which is clearly separate from that of the White Maiden, appears only three times throughout the Venus Tables (Figure 12b). The name glyph is characterized by a prominent moon sign in the back of her head, a feature never found in association with the White Maiden.

Thus, Goddess I, or sak ixik as her name is rendered in the Dresden Codex, is clearly not the Moon Goddess, contrary to earlier interpretations, including my own (Seler 1902-23, IV: 738; Thompson 1939, 1972: 47-48; Grube 2012: 51). Rather, she is a youthful goddess paired with with male deities and stated as being their wife (yatan) (Houston 2018: 33). Sometimes she is portrayed as aged in the Madrid Codex (Figure 11e), and is associated with weaving and childbirth (cf. Bassie-Sweet 2008: 202 ). The image on the Princeton vase suggests that multiple incarnations of the White Maiden may have existed simultaneously and confirms her role as an attendant of God L in his underworld palace. Perhaps the White Maiden can also be interpreted as the divine equivalent of the noble ladies at the royal courts, who are often clad in white dresses in the art of the Classic period. It is perhaps no coincidence that all the women in Bonampak's paintings wear white cl oaks.

|

|

| a | b |

| Figure 12. Moon Goddess in the Venus Tables: a) Dresden 49: The only depiction of the Moon Goddess carrying a lunar crescent in the Codices (digitized image, SLUB Dresden, Public Domain Mark 1.0); b) Her distinct name glyph, marked by a moon sign at the back of her head, occurs three times in the Venus Tables and is never associated with the White Maiden. | |

During the Classic period, the White Maiden was the personification of the number two, much like the maize god Ixiim personified the number one, and the wind god personified the number three. This reinforces the idea that all personified numbers were deities and highlights that there is no direct correlation between the number and the name of the deity.

The White Maiden was also the personification of the color sak . This strong association with the color is evident in the consistent use of the SAK prefix in many versions of her name, spanning from the Classic inscriptions to the Postclassic codices. In Mayan languages, sak , in addition to meaning “white,” also conveys the symbolic meanings of “bright” and “clean,” and describes the quality of something as “artificial” (Houston et al. 2009: 33). It has been frequently cited that the presence of sak links the goddess to weaving, because in Yucatec sakal translates as “weaving” (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 710). This entry could be a survival of an old association of the white maiden with the production of textil es. Other lexical entries In colonial period Yucatec Maya also point to a connection of sak ixik with female menstruation: zacalixic "menstruo de la muger y su regla" (Martínez Hernández 1929: 216; cf. Houston 2012b, 2018: 33). In combinatlon with parentage terms, sak indicates a "false" or "unperfect" parentage, such as zac mehen "entenado o hijastro respecto del varón, esto es, que es hijo de su muger ávido con otro marido" (Martínez Herández 1929: 219) and zac yum "padrasto" (Martínez Hernández 1929: 218).

The color white, moreover, is traditionally associated with the north. It is therefore plausible that the north was regarded as the home of the White Maiden, likely because it also served as the location of God L’s underworld palace. This association with the north may also explain why, on Piedras Negras Stela 3, her glyph replaces the more common naahal "house, north" glyph used for the 7th Lord of the Night, and why, on Copan Stela 5, the personification of the number two is linked to a NAAH logogram referencing the north.

The interpretation of the White Maiden’s name glyph remains problematic, primarily due to the lack of a phonetic substitution for Graph 1086vc, the hand with the fist. Nonetheless, the accumulated evidence presented here allows us to identify an additional deity in the Maya pantheon and trace the roots of the Postclassic Goddess I ( sak ixik ) back to this newly identified White Maiden of the Classic period.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to my colleagues of the Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya project, Elli Wagner, Christian Prager and Guido Krempel for their contributions and corrections. I also thank María Elena Vega and Cathryn Nuckols for insightful conversations about the role of women in Maya society and the personification of colors and numbers in Maya writing.

References

Anders, Ferdinand

1967 Codex Tro-Cortesianus (Codex Madrid): Museo de America Madrid. Codices selecti phototypice impressi 8. Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt, Graz. Ara, Domingo de

1986 [1571] Vocabulario de lengua Tzeldal segun el orden de Copanabastla. Edición de Mario Humberto Ruz. Fuentes para el Estudio de la Cultura Maya 4. Centro de Estudios Mayas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D.F.

Aulie, H. Wilbur, and Evelyn W. Aulie

1978 Diccionario ch’ol-español, español-ch’ol. Serie de Vocabularios y Diccionarios Indígenas, Mariano Silva y Aceves 21. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, México, D.F.

Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo (ed.)

1980 Diccionario Maya Cordemex: Maya-Español, Español-Maya. Ediciones Cordemex, Mérida.

Bassie-Sweet, Karen

2008 Maya Sacred Geography and the Creator Deities. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Boot, Erik

2003 Colors and Associated Cardinal Directions on an Unprovenanced Late Classic Maya Ceramic Bowl. http://www.mayavase.com/bootcolors.pdf

Coe, Michael D.

1973 The Maya Scribe and His World. The Grolier Club, New York.

Freidel, David, Linda Schele, and Joy Parker

1993 Maya Cosmos. Three Thousand Years on the Shaman’s Path. William Morrow, New York.

Grofe, Michael J.

2014 Glyphs G and F: The Cycle of Nine, the Lunar Nodes and the Draconic Month. In Archaeoastronomy and the Maya, edited by Gerardo Aldana y Villalobos and Edwin L. Barnhart, 135–156. Oxbow Books, Oxford.

Grube, Nikolai

1990 Die Entwicklung der Mayaschrift. Grundlagen zur Erforschung des Wandels der Mayaschrift von der Protoklassik bis zur spanischen Eroberung. Acta Mesoamericana 3. Verlag von Flemming, Berlin.

2012 Der Dresdner Maya-Kalender: Der vollständige Codex. Herder, Freiburg.

Grube, Nikolai, and Marie Gaida

2006 Die Maya: Schrift und Kunst. SMB DuMont, Berlin and Köln.

Houston, Stephen D.

2012a Maya Writing: Modified, Transformed. In The Shape of Script: How and Why Writing Systems Change, edited by Stephen D. Houston, 187-208. School for Advanced Research Press, Santa Fe.

2012b Heavely Bodies. Maya Decipherment: Ideas on Maya Writing and Iconography. Electronic document. https://mayadecipherment.com/2012/07/16/heavenly-bodies/

2018 The Gifted Passage: Young Men in Classic Maya Art and Text. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Houston, Stephen D., Claudia Brittenham, Cassandra Mesick, Alexandre Tokovinine, and Christina Warinner

2009 Veiled Brightness. A History of Ancient Maya Color. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Houston, Stephen D., and Takeshi Inomata

2003 The Classic Maya. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Hull, Kerry

2016 A Dictionary of Ch’orti’ Mayan-Spanish-English. The University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Iglesia, Martin de la, Franziska Diehr, Uwe Sikora, Sven Gronemeyer, Maximilian Behnert-Brodhun, Christian M. Prager, and Nikolai Grube

2021 The Code of Maya Kings and Queens: Encoding and Markup of Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative Issue 14. https://journals.openedition.org/jtei/3336.

Kaufman, Terrence S.

2003 A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. University of Chicago, Chicago.

Kaufman, Terrence S., and William M. Norman

1984 An Outline of Proto-Cholan Phonology, Morphology, and Vocabulary. In Phoneticism in Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing, edited by John S. Justeson and Lyle Campbell, 77-166. Publication 9. Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, State University of New York, Albany.

Lounsbury, Floyd

1984 Glyphic Substitutions: Homophonic and Synonymic. In Phoneticism in Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing, edited by John S. Justeson and Lyle Campbell, 167-184. Publication 9. Institute for Mesoamerican Studies, State University of New York, Albany.

Maler, Teobert

1908-10 Explorations of the Upper Usumatsintla and Adjacent Regions. Memoirs IV. Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Martínez Hernández, Juan (ed.)

1929 Diccionario de Motul Maya-Español, atribuido a Fray Antonio de Ciudad Real y arte de lengua maya, por Fray Juan Coronel. Edición hecha por Juan Martínez Hernández. Talleres de la Compañía Tipográfica Yucateca, Mérida.

Mayer, Karl Herbert

1984 Maya Monuments: Sculptures of Unknown Provenance in Middle America. Verlag Karl-Friedrich von Flemming, Berlin.

1995 Maya Monuments: Sculptures of Unknown Provenance, Supplement 4. Academic Publishers, Graz.

Palacios, Enrique Juan

1936 Inscripción recientemente descubierta en Palenque. Maya Research 3: 2-17.

Prager, Christian, and Sven Gronemeyer

2018 Neue Ergebnisse in der Erforschung der Graphemik und Graphetik des Klassischen Maya. In Ägyptologische “Binsen”-Weisheiten III: Formen und Funktionen von Zeichenliste und Paläographie. [Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Abhandlungen der Geistes- und sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse 15], edited by Svenja A. Gülden, Kyra V. J. van der Moezel, and Ursula Verhoeven-van Elsbergen, 135–181. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart.

Rosny, Léon de

1883 Codex Cortesianus, Manuscrit hiératique des anciens Indiens de l’Amérique Centrale conservé au Musée Archaéologique de Madrid, photographié et publié pour la première fois avec une introduction et un vocabulaire de l’écriture hiératique yucatèque. Libraries de la Société d’Ethnographie, Maisonneuve, Paris.

Schele, Linda

1987 Some Ideas of the Protagonist and Dating of Stela E. Copan Note 25, Copan Mosaics Project, Copan.

1989 A New Glyph for “Five” on Stela E. Copan Note 53. Copan Mosaics Project, Copan.

Seler, Eduard

1902-23 Gesammelte Abhandlungen zur amerikanischen Sprach- und Alterthumskunde. 5 Vols., Ascher, Berlin

SLUB Dresden

Der Dresdner Maya-Codex. Electronic Document. https://www.slub-dresden.de/entdecken/handschriften/maya-handschrift-codex-dresdensis

Stuart, David

1987 Ten Phonetic Syllables. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 14. Center for Maya Research, Washington, D.C.

1998 Architecture and Ritual in Classic Maya Texts. In Function and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture, edited by Stephen D. Houston, 373-425. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

Taube, Karl Andreas

1992 The Major Gods of Ancient Yucatan. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology 32. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

Thompson, John Eric S.

1939 The Moon Goddess in Middle America with Notes on Related Deities. Contributions to American Anthropology and History 5 (29): 121-173. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C.

1950 Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: An Introduction. Publication 589. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D.C.

1962 A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK.

1972 A Commentary on the Dresden Codex. American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

Tozzer, Alfred M.

1941 Landa’s Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán: A Translation, Edited with Notes. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University 9. Cambridge, MA.

Velásquez García, Eric

2009 Reflections on the Codex Style and the Princeton Vessel. The PARI Journal 10(1): 1-16.

Villagutierre Soto-Mayor, Juan de

1983 [1701] History of the Conquest of the Province of the Itza. Edited and with Notes by Frank E. Comparato. Labyrithos, Culver City.

Wagner, Elisabeth

2003 The Female Title Prefix. Wayeb Note 5. https://www.wayeb.org/notes/wayeb_notes0005.pdf

Zender, Marc

2000 A Study of Two Uaxactun-Style Tamale-Serving Vessels. In The Maya Vase Book 6, edited by Justin Kerr: 1038-1055. Kerr Associates, New York.

Zimmermann, Günter

1956 Die Hieroglyphen der Maya-Handschriften. Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiet der Auslandskunde, Reihe B: Völkerkunde, Kunstgeschichte und Sprachen 62. Cram, de Gruyter, Hamburg.

- As part of our work on a new catalog of Maya signs and their graphs, we have been evaluating and revising Thompson’s Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs (1962). We are critically scrutinizing his system with the help of his original grey cards and supplementing it with signs that were not included in Thompson’s original catalog. Despite its known shortcomings and incompleteness, his catalog is still regarded as the standard work for Maya epigraphers, which is why we adopt Thompson’s nomenclature while removing misclassifications and duplicates, merging graph variants under a common nomenclature, and adding new signs or allographs to the sign index in sequence, starting with the number T1500. Allographs are also further organized with the help of newly defined classification and systematization criteria, which we described in detail in Prager and Gronemeyer (2018). In the transliteration of Maya hieroglyphic script, bold typeface is employed, with uppercase letters representing LOGOGRAPHIC signs and lowercase letters denoting syllabic signs. To accurately describe the spatial arrangement of glyphs within a hieroglyphic block, the notation system established by Günter Zimmermann (1956) and Eric Thompson (1962) is utilized. This convention, also adopted by the Project Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan, specifies that adjacent glyphs are separated by a period (.), vertically stacked glyphs by a colon (:), and distinct segments comprising groups of glyphs within the hieroglyphic block are enclosed in square brackets [ ]. When a glyph is embedded within another, it is indicated by a degree symbol (°) (cf. Zimmermann 1956), whereas the fusion of two glyphs is denoted by a plus sign (+) (cf. Iglesia et al. 2021). T-numbers in the transliterations denote undeciphered signs and reference Thompson's Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs .

- All illustrations are by Nikolai Grube, unless otherwise stated, and are available under the Creative Commons CC-BY 4.0 license.

- The vessel belonged to a Sihyaj Chan K’awiil of Namaan, who was also a k’uhul chatahn winik . There are several ceramics from the very beginning of the Late Classic period from the western Petén region which mention chatahn winik people, suggesting that during this period there might have been a stronger presence of members of this family in that part of the Maya lowlands. In later times, the chatahn winik title has a more limited distribution focusing on the area of the northern Peten and southern Campeche.

- The name for this kind of atole is variously given as saka’ and sak-ha’ in Yucatec dictionaries. Today, the gruel is known as saka’ and is prepared simply of cooked ground maize mixed in water. According to Villagutierre Soto-Mayor, zaca was a drink made of cacao and maize. Landa, on the other hand, identifies sacah as a ceremonial drink of water and maize only (Tozzer 1944: 89,90; 140; see also Grube and Gaida 2006: 76-77).

- Ch’ol juy “mover con palo (atole o pinole)” (Aulie and Aulie 1978: 70); Chorti jujyi “batir” (Hull 2016: 181); Yucatec huy “menear alrededor, mecér algún licor, revolver a la redonda con cuchara o palo” (Barrera Vásquez et al . 1980: 260); Tzeltal ghuy “revolver, como para cocer miel, leche, etc.” (Ara 1986: 297).

- The xaman glyph appears in Baking Pot, Coba, Copan, Ek Balam, Hwasil, Ixlu, La Corona, Naranjo, Palenque, Quirigua, Tonina and numerous artifacts of unknown provenance.

- The first occurrence of the xaman glyph is on Coba Stela 11, dated 9.10.0.0.0 (633 CE). Given the fact that xaman is a Yucatecan word for north, it is possible that it was introduced into the lowlands from proto-Yucatecan speakers originating in or around Coba.

- The fact that the name is spelled as IXIK-ki confirms once more that the Codices were written in a language contact situation where Yucatec speaking scribes wrote and memorized an ancient lingua franca that was based on Classic Mayan, a language closely linked to (Eastern) Ch’olan.