und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

JOM: A Possible Reading for the “Star War” Glyph?

Research Note 25

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.21.rn025.en

Dimitrios Markianos-Daniolos (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

This research note is based on a chapter from my master’s thesis which discusses the possible readings of the Star War glyph. In that thesis, I attempt to provide the most up-to-date and complete examination of this sign. The insights gained from this investigation now allow us to draw new conclusions and re-evaluate our understanding of this enigmatic term. This article will discuss one of the new ideas that arose from this study, specifically a hypothesis that may yield a new reading proposal.

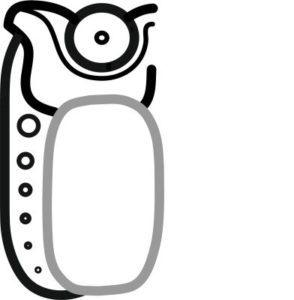

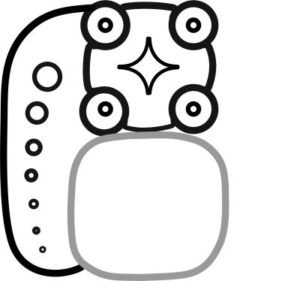

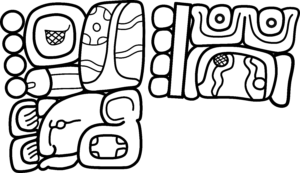

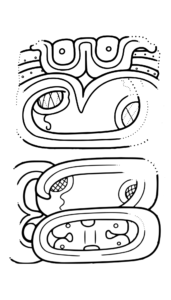

With at least 54 confirmed individual appearances in the Maya script, the Star War glyph has been used to record at least 41 events, while two additional occurrences form parts of non-verbal phrases. In terms of structure, the sign has been observed to have several graphs (Figure 1), all of which record the same action.

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

From the substitutions and spelling variations observed, it can be concluded that no consistent patterns are observed in terms of graph use. The graph known as “star-over-earth” most likely forms the complete variant of the Star War glyph, as it can substitute for every other Star War graph. The syllables –yi and –ya are often attached to the Star War glyph, the former producing the -V1y mediopassive suffix, while the latter likely acts as a temporal deictic marker. One case of nominalisation has been observed, as seen on Piedras Negras Throne 1 where the syllable –la acts as a nominaliser, indicating qualitative abstraction. The Star War glyph has also been observed to take on numerical coefficients, as well as the preposition ti , which may be indicative of some directionality.

There are several contexts in which this term appears. Most commonly, the Star War glyph is used to record the result of historical battles, where it is used to express the downfall of military forces, cities, or dynasties. The implications of these events seem to vary, but in some cases led to severe consequences and the formation of dependencies between polities. These historical Star War events have not been observed to be timed to the movements of celestial bodies such as the planet Venus, meteor showers, or comets. A preference is visible regarding certain moon phases, as well as cycles relating to agriculture and the seasons, however such patterns are also common among other verbs used in the context of warfare.

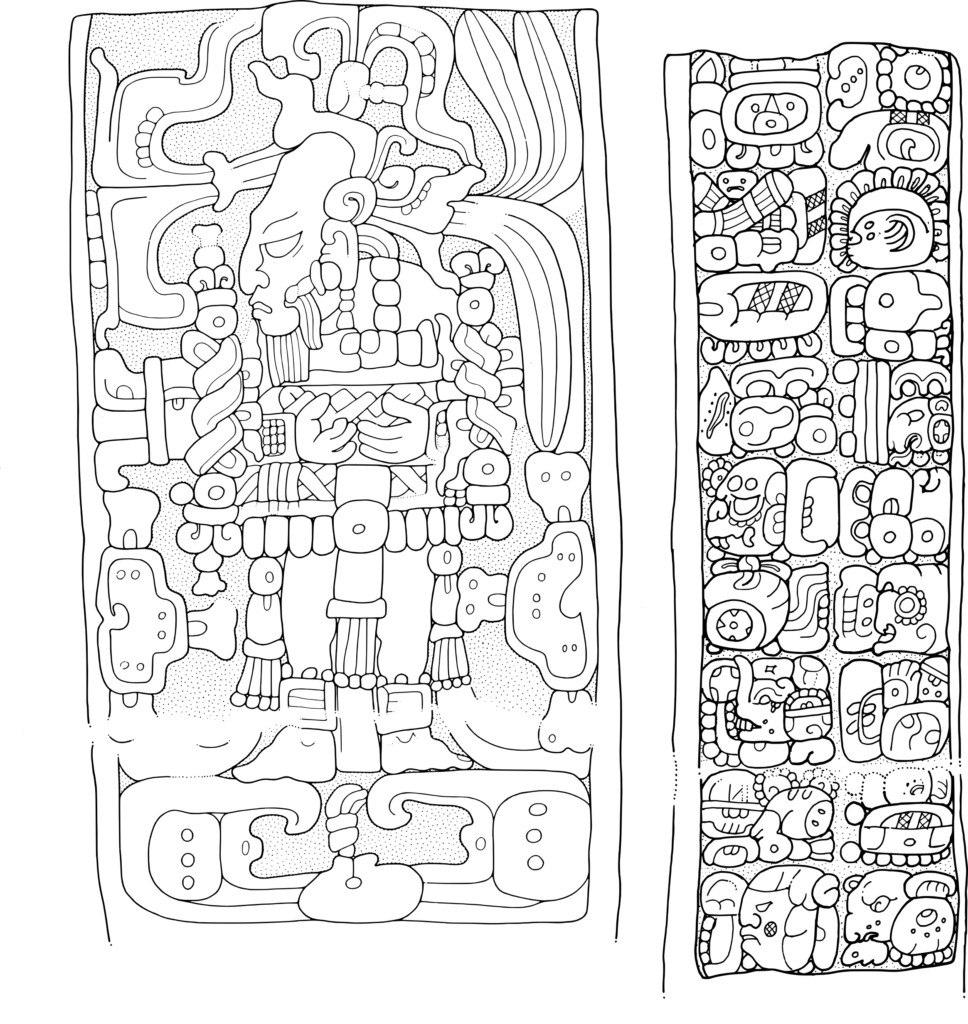

Aside from that, the Star War glyph can appear in contexts that have nothing to do with warfare. In mythological contexts, the Star War glyph has been used to record events such as the sinking of the Maize God’s canoe, as seen on several carved bones from Tikal and the Star War Vase, which correspond to the violent weather conditions that are visible in the accompanying iconography. The glyph also appears in contexts relating to k’atun prophecies, as seen in the Paris Codex. Finally, the Star War glyph was probably also used in topographic references. On Piedras Negras Throne 1, a ceremony is recorded, taking place in the central sector of the city. In the phrase tu “star war”-l tahn ch’een ? tuun (Figure 2) the Star War glyph may form part of a precise locative expression. A rough translation may be “at the ‘star war quality’ of the centre of the settlement, at the Paw Stone”. Stuart (2004a) has demonstrated that the “Paw Stone” glyph likely refers to Piedras Negras Altar 4 which was found in the East Group Plaza of the site. Therefore, the text on the throne probably records an event that took place in the East Group Plaza of Piedras Negras, near Altar 4.

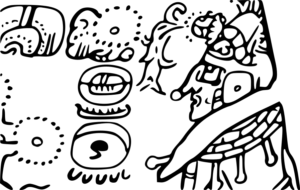

It is possible that in this case, the Star War glyph refers to a quality attributed to the central sector of Piedras Negras. Looking at a map of the site, one sees that the East Group Plaza is one of the largest flat areas in this part of the site, sitting at the feet of a steep hill. Moving toward the river, between the East Group Plaza and Sector O/N one encounters a drop in elevation, or a split in the terrain. It may be that the Star War glyph is used to describe features of the land such as the sharp decline in elevation or a split in the landscape. The important distinction here being that it is the tahn “centre” of the ch’een that “goes down”, and not the ch’een itself. We may be looking at a precise locative expression referring to a place or a topographic feature in the vicinity of the East Group Plaza. Additionally, on the Palenque Initial Series Vase, a Star War glyph is followed by a phonetically spelt kab “earth” reference (Figure 3). The phrase bolon “star-over-earth” kab may also refer to features of the earth or the landscape, acting as a potential toponym.

In terms of iconography, the Star War sign and its graphs have been related to mythical beings and events such as the Starry Deer Crocodile and its decapitation which led to a cosmic deluge (Wagner 2009; Rivera 2018:323). Scenes such as the Star War Vase provide additional information, where the raining star is associated with heavy meteorological forces (Zender 2020). These contexts associate the Star War graphs with the night sky, the underworld sky, dark environments, storms, and deluges. Such interpretations can be supported by parallels found in Maya iconography, and provide a good approximation to what the Star War graphs might actually represent.

Having outlined some of the key conclusions drawn from that investigation, I will move on to the reading of the glyph. In the past, numerous reading proposals for the Star War glyph have been put forward. The majority of them, revolve around the general sense of “sinking” or “going down” (Table 1).

| Researcher (1)** | Reading Proposal | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Closs (1979) | kab ek’, ek’ box | “earth star”, “black star” |

| Kremer & Voss (1993) | bul | “to sink, submerge” |

| Lacadena (1995) (2)** | ts’ay/ts’oy | “to come down” |

| Boot (1995) | hay/haykah | “to destroy/destroy towns” |

| Stuart (1995) | jub | “to topple, go down” |

| Velásquez García (2002) (3)** | chek/tek | “to step on, to kick, to humiliate” |

| Zender (2005) (4)** | ch’ay | “to be defeated, go down” |

| Aldana (2005) | ek’emey | “to descend, go down” |

| Kremer (2006) | t’ub | “to sink” |

| Chinchilla Mazariegos (2006) | uk’ | “to cry, to weep, to lament” |

| Prager (2009) (5)** | nay | “to lean over, fall down, smash |

| Prager (2018) (5)** | lub | “to fall, sink, fall flat on the earth” |

The problem is, that due to the sheer variety of sinking-related terms found in Mayan languages, it is difficult to find a reliable root in dictionaries that truly fits the description. This is coupled with the absence of any Star War phonetic complements that are legible, making the search for a reading even more challenging. The fact that on Piedras Negras Throne 1 a tu -preposition precedes it, indicates that the Star War root is likely consonant initial. Many of the previous reading proposals favour a CVC root. However, in other publications, some researchers have favoured a CVY root and point to the –yi suffix that is often attached to the Star War glyph as evidence for such a structure (Boot 1995; Kinsman n.d.). More recently, the Star War occurrence on Piedras Negras Throne 1 has been proposed to be a unique example where phonetic complementation is the only possible explanation (Zender 2020:68). Since this occurrence is nominalised, the –yi syllable would serve no other purpose other than act as a phonetic complement. However, another explanation may also apply. The –yi syllable consistently acts as a spelling for the mediopassive suffix, something also seen in other verbs recording motion. Following that, an alternative explanation may be that we are looking at an example of “fossilised spelling” where the –yi has become an incorporated visual component of the glyph. Since the –yi syllable is extremely common in Star War spellings (with at least 23 occurrences, all of which work as mediopassive suffixes), it may have ended up as a visual component of the Star War glyph. Piedras Negras Throne 1 was commissioned in 785CE, which would make this Star War occurrence one of the latest examples in the Classic Period. On top of that, such a phenomenon has been observed before in Maya scribal practices, for instance on page 61 of the Dresden Codex, one finds an u-LOK’-yi spelling that is meant to be read as u-LOK’. An example from the Classic Period can be found on vase K1775 in the Kerr Catalogue, where a T’AB-yi spelling is observed, but with an additional –yi infixed in the /T’AB/ logogram. Such practices have been interpreted as conventional conflations (Gronemeyer 2014:402), and show that such examples, although rare, did exist in Maya scribal traditions. Admittedly, this is more of a paleographic argument than a linguistic one, but it might offer an alternative explanation to the unique spelling we see on Throne 1 of Piedras Negras.

In terms of semantics, due to the absence of any clear phonetic complements, one must take into account every single context the Star War glyph appears in, to find a term that semantically corresponds to it. Several of the previous Star War reading proposals do not satisfy all of its known semantic fields, while others provide promising cases but do not exceed each other in terms of likelihood. As seen in Table 1, some reading proposals that primarily have to do with “sinking”, “submerging”, or “falling” constitute good contenders in the search for a Star War reading. However, in the process of examining the Star War glyph, I came across an alternative possibility, one which I would like to share in this article.

The couplings taj “obsidian” and took’ “flint” appear to characterise the “face” or “eyes” of the War Serpent. The glyph that follows probably reads u-lok’oom, which based on similar dictionary entries, might be understood as a reference to the image of someone, although its exact meaning remains uncertain. This is followed by the name of K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’, the founder of the Copan dynasty, whose name is followed by Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat, who most likely ruled Copan at the time the monument was erected. It is possible that the two names may act as a temporal parenthesis which included all Copan rulers in between, but that too remains uncertain. Another interpretation may see u-lok’oom as a reference to the “taking away” or “removing” of K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’ by Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat (Guenter 2020:241). According to Guenter (Guenter 2020:243), Copan Stela 11 does not record a past event, but a prophecy. This prophecy might retrospectively refer to a previous 8 Ajaw k’atun, which fell in the mid-6th century and could reference the downfall of Teotihuacan itself. This might even have older origins, going back to the Preclassic collapse. The implication here being, that Stela 11 was produced during the reign of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat and records a prophecy foretelling the demise of the Copan dynasty, linking it to that of Teotihuacan 13 k’atuns earlier. Alternatively, it may simply record the collapse of divine authority at Copan, signalling the demise of a dynasty (Stuart 1993:345-346). In either case, the verb jomooy appears to be an apt descriptor for a grand downfall event.

The verb root jom is very rare in Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions, but it holds meanings that are surprisingly similar to the ways Star War glyph has been used. To explore this idea, I will provide a summary of dictionary entries corresponding to four semantic fields, the full list of which can be found in the Appendix. After that, a short discussion will follow, assessing the likelihood of /JOM/ being the reading of the Star War glyph.

The first and most common meaning of jom in Mayan languages, is the general act of sinking or plunging into a hollow area. The dictionary entries gathered, show that such meanings are found in all linguistic branches of Mayan languages. For instance, the colonial Yukatek home or homah means “to push into an abyss” (Bolles 2001:1746), while other terms in Yukatek include jomik “hundir, desfondar” (Yoshida 2009:28), hom or hóom “remove bottom” (Bricker 1998:110), which give an idea as to the general meaning. Other Yukatekan languages include similar terms, for instance in Itza one finds jomik “make a hole, perforate”, jomk’otak “ready to collapse” (Hofling and Tesucún 1997:318-319), in Mopan there is jom “sink” (Hofling 2011:221), and in Lacandon jüooman “break up”, jóomsik “make a hole in”, and jo’m-jo’m “collapsed” (Hofling 2014:159). In Cholan languages, Chontal provides some examples, such as hom “to sink, fall in” (Knowles 1984:423) and jome “to sink” (Keller and Luciano 1997:139). Additional examples are seen in Q’anjob’alan languages, for example Akatek has homloi or homlui “hundirse” (Andrés et al. 1996:56), and Chuj has jom “escarpar” (ALMG 2003a:42). Mamean and K’iche’an languages also have similar terms, such as the Tektitek jomil “agujerear, hacer uno o más agujero en la tierra” (Simón Morales and Gutierez 2007:120), or the K’iche’ jomojik “deep, sunk” (Ajpacajá Tum et al. 1996:99). These examples show that common meanings of jom include sinking, falling in, digging, making holes, and submerging.

The second meaning of jom has to do with destruction, violence, and disruption. There are terms referring to the destruction of buildings for instance in colonial Yukatek we see homchahal cah “perderse, destruirse, o hundirse el pueblo” (Ciudad Real 2001:259) or homah “derribar edificios” (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) (7). In Chontal one finds a more explicit example, with homole meaning “war” (Knowles 1984:423). Tojolab’al also presents us with relevant terms relating to destruction, violence, and confounding, e.g. jomi “descomponerse, destruirse, degenerar, atarantarse, confundirse, arruinarse” (Lenkersdorf 2010:273). Similar terms relating to disruption and breakage are seen in examples such as the colonial Tzeltal homen “desbaratado” (Ara 1986:47), the Tzotzil jomol “roto, perforado” (Delgaty and Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66), and the Poqomaam homel “desolación, calamidad, destrucción, estrago, clades, exterminación, vastitar” (Feldman 2000:116).

So far, these semantic areas are also covered by most previous Star War reading proposals, and are the meanings most commonly associated with the Star War glyph. However, two more meanings exist which make jom stand out. The first one, is a general sense is of “caving in” but is mostly applied to landscapes, and is found in most Mayan languages. In Yukatek for example, hom refers to features such as ditches, pits, sinkholes, ridges, abysses, and the “sinking” of the land. Some examples of this may be the Yukatek hom “zanja, abismo” (Kaufman 2003:992; Michelon 1976:147), or jom “zanja, hoyo o barranca oscura” (Gómez Navarrete 2009:135; Ciudad Real 2001:258). In other Yukatekan languages one finds similar terms, such as the Mopan jomoc a lu’umu “hay un lugar hundido en la tierra” (Ulrich and Ulrich 1976:103; ALMG 2003b:42) while in Lacandon we see jo’m ru’um “collapsed land”, amongst others (Hofling 2014:159). In other linguistic branches there are similar terms referring to features of the landscape, such as the Akatek homoni “estar bien hundido (tierra)”, or homkiltaj “tierra hundida” (Andrés et al. 1996:56), or the Tzotzil homal and sjomal “gorge, narrow valley” referring to the split of objects or the landscape (Laughlin 1975:157; Laughlin and Haviland 1988:213; Delgaty and Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66). Interestingly, in K’iche’ and Kaqchikel, hom or jom are used to refer to ballcourts, another “sunken area” (Edmonson 1965:41; Rodríguez Guaján 1990:59).

One last semantic field of jom that needs mentioning, has to do with meteorological phenomena which would be especially important in the context of the Star War glyph. Important terms come from colonial Tzeltal e.g. homel “diluvio”, hom “hacerse diluvio”, homel haal “agua grande” (Ara 1986:47). Although fewer in number, other terms can be found in Mayan languages, which relate to natural phenomena such as the Yukatek hom kaknab “alterarse y embravecerse la mar” (Heath de Zapata 1978:258), hom “crecida mar o río” (Ciudad Real 2001:254) while the Barrera Vásquez dictionary also relates it to high tides and raging seas (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229). Other languages relate jom to strong winds, hurricanes, the humidity of the earth, and rushing water, as seen in the Appendix.

In the Chilam Balam book of Chumayel, one finds an interesting example concerning the end of the world, which took place when a group of underworld deities named Bolontiku captured Oxlahuntiku. This was followed by a “sudden rush of water” and then ti homocnac canal, homocnac ix ti cab... “the sky would fall, it would fall down upon the earth…” (Roys 1967:99-100). There are several reasons why this passage is interesting. As seen in previous passages, the author appears to use the verb root hom , in this case describing the events that would transpire during the end of the world. The “sudden rush of water” and “falling of the sky upon the earth” strongly resemble the imagery we see in the star-over-earth graph of the Star War glyph. When discussing this passage, Zender noted the similarity between the name Bolontiku and the Classic Maya group of deities named Bolon Yokte’ K’uh (Zender 2020:70). In fact, Bolon Yokte’ K’uh are credited with the Star War event against the Maize God and the stormy conditions seen on the Star War Vase, through the oblique phrase ukabjiiy “under the authority of”. Furthermore, after the destructive event described in the Chilam Balam passage, trees are set up in the corners of the world, eventually followed by the creation of the world (Roys 1967:99-100). At this point, scenes such as the Vase of the Seven Gods or the Vase of the Eleven Gods come to mind, where world-creation is the dominant theme. Bolon Yokte’ K’uh, among other deities have gathered in front of God L, with bundles of Star War glyphs appearing in front of them. It may be that such events involved the creation of trees, earth, and celestial bodies (Prager 2013:493). Therefore, several references from the Chilam Balam of Chumayel make use of the root jom to recount important events involving destruction and creation that may be relevant to the Star War glyph. This destructive and creative aspect might also be seen in the myths already connected to the Star War glyph, such as the decapitation of the Starry Deer Crocodile that caused a giant flood. However, although such parallels may appear compelling, these links are highly speculative. Further evidence is needed to securely interpret and establish links between such passages and Star War imagery, something also noted by Zender (2020:70).

Other interesting occurrences of jom can be found in Ritual de los Bacabes where one encounters tan homlah kab “en las profundidades de la tierra” (Arzápalo 1987:217), and hom kab “en las cavernas de la tierra” (Arzápalo 1987:309). Such examples, further demonstrate the semantic areas in which jom can be used.

In terms of grammar, jom appears to be a root transitive verb in most languages, however exceptions can also be found. In his analysis, Wald (2007:294) cites intransitive examples from Chontal, and Tojolab’al which have both transitive and intransitive forms. However, according to Wald, the latter may be based on earlier mediopassive forms, since many Spanish translations end in –se. It should also be noted that in the examples available, jom is a verb that works with the ti and ta prepositions e.g. in Chontal (Keller and Luciano 1997:139), which is also observed in some Star War examples.

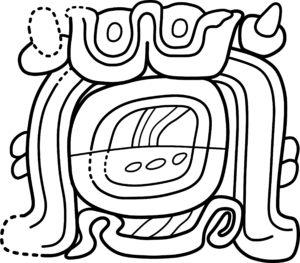

It should also be said that in the past, the example on Copan Stela 11 has been translated as “it finishes” (Schele and Freidel 1990:343) and was interpreted as referring to the “termination” of the dynasty. However, Stuart (1993:345-346) also noted the destructive meanings in Yukatek, related the event to the mutilation of structures, and connected the inscription to the Classic Period collapse. Another example of the verb jom being used in Maya hieroglyphic texts comes from a ceramic sherd from Buenavista del Cayo (Reents-Budet et al. 2000:104, Fig. 6a; Reents-Budet 1994:81). The full text on the sherd is not well understood, but the last three glyph blocks spell out jomo’w iik ? and record an action by an unknown subject (Figure 5). This subject cannot be identified but the glyph has been associated with Itzamnaaj before (Helmke 2012:114), who is depicted next to the text.

This is of course not an example of substitution, but at least it shows that the same toponym can appear both in a Star War example as well as in a jom example. Just like the occurrence on Copan Stela 11, the verb on the sherd has also been translated as “he finishes”. However, perhaps a more fitting translation for both occurrences may be “sinking”. This might be because the meaning of sinking is more common and widely distributed in Mayan languages, whereas translations referring to “ending” or “termination” are fewer (Garay Herrera 2017:100-101). Furthermore, as outlined earlier there are many examples connecting jom with natural formations such as sinkholes, caves, or caverns. This may be especially appropriate in the context of Copan Stela 11, since the ruler dressed as the Maize God stands above a giant cenote sign. Both sides of the scene display water-shell motifs that usually appear in the context of the watery underworld. In this scene, the ruler appears in the guise of the Maize God emerging from a sinkhole presumably after having sunken in.

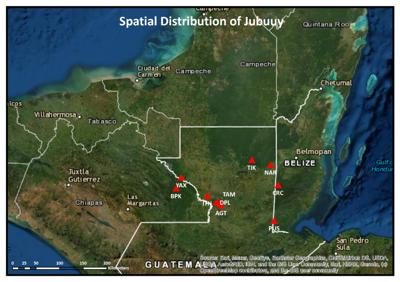

Having covered the linguistic background of the verb root, I will now briefly discuss how a potential /JOM/ reading of the Star War glyph may fit in the relevant contexts. Most Star War occurrences appear in historical militaristic inscriptions, where the downfalls of rulers, military forces, and cities are recorded. In such contexts, translations such as “sinking” or “collapsing” may be appropriate to describe the results of conflicts, while additional meanings such as the violent and destructive translations of jom may also be fitting. It may also be that extreme weather phenomena were seen as appropriate metaphors in the context of warfare. In such cases, the “sinking” of a ruler or their military force would probably be metaphorical. Furthermore, it may not be a coincidence that the Star War glyph takes on terms such as kab ch’een or simply ch’een as its subjects, unlike other verbs of motion, such as jub . This might be important considering the close connection jom has with landscapes, terrains, and geographical features. The “sinking”, “getting a hole”, or simply “caving in” of one’s kab ch’een would fit well in the context of jom .

When it comes to mythology, the Star War glyph appears in scenes such as the sinking of the Maize God’s canoe, as seen on bones MT-38A, MT-38B, MT-38D, MT-50 from Tikal, as well as the Star War Vase. In this context, a jom reading would be more literal, as it would record the submerging of the canoe in the dark watery underworld. It must be noted, that the sinking of the Maize God’s canoe appears to be part of a longer narrative which may be connected to agriculture-related mythology. While examining dictionary entries relevant to the verb root jom , I came across many examples of the term being used in the context of maize, especially rotten maize. Examples such as the Tzotzil hom “scooping up corn in hands and sloshing in water” (Laughlin 1975:158), may have some relevance in the context of agricultural terms. However, such maize-related terms may not share the same root as the other uses of jom and are therefore unreliable.

In terms of iconography, the Star War glyph has been associated with storms, deluges, and harsh weather conditions. For instance, on the Star War Vase, a giant star appears above the Maize God’s canoe navigating through choppy waters, while rain appears to be falling throughout the scene. There may also be iconographic links between the Star War glyph and the decapitation of the being known as the Starry Deer Crocodile, which may link it to floods or deluges. With regards to the graphs of the Star War glyph, they most likely depict a star with water, or some type of fluid falling or bursting from its sides. In this context, dictionary entries of jom relating it to storms and deluges, e.g. the colonial Tzeltal homel “diluvio” or hom “hacerse diluvio” (Ara 1986:47) would be especially fitting. The meteorological forces associated with the Star War graphs correspond well with terms from different Mayan languages that refer to storms, deluges, floods, strong winds, and raging seas.

An especially interesting case can be seen on Throne 1 of Piedras Negras. As mentioned previously, it is possible that the Star War occurrence found in the throne text acts as a topographic reference by referring to features in the landscape of central Piedras Negras. This may be a decline in elevation, a “split” in the landscape, or even a flat area such as the East Group Plaza. Such features may be visible in maps of the site, where the landscape “goes down”. Thus, the text may act as a very precise reference to the setting in which the ceremony took place, most likely in the vicinity of the East Group Plaza. If this interpretation is correct, it would fit many of the topographic meanings of jom . Terms such as the Yukatek homil “la parte hundida” (Pérez 1866-1877:137), hom “hundimiento de la tierra” (Kaufman 2003:992), or the Tzotzil homal “gorge, narrow valley” (Laughlin 1975:157) come to mind, which would be describing the shape of the landscape in central Piedras Negras. A preliminary translation may be “at the sinking/dipping of the centre of Piedras Negras”.

There, the Star War graph used is a star-over-earth variant, but a cleft or opening is seen in the earth sign. In what may be an example of powerful wordplay, this Star War occurrence describes the act of “sinking” or “caving in” of one’s kab ch’een while at the same time alluding to the topographic meanings of jom , thus giving away the reading of the sign. This is probably the oldest confirmed Star War occurrence, dating to the 6th century which is what makes it so unique. While briefly commenting on this occurrence, Stuart (2011:298) suggested this graph may have to do with opening or breakage. Alternatively, one could see this opening not as a reference to breakage, but of “caving in” or simply a “dipping” of the landscape. This might be because similar graphs, such as those of the /PA’/ sign, usually exhibit sharp cracks or fissures pertaining to breakage, whereas this Tonina fragment shows a wider split in the earth sign. Of course, one example is not enough to support such subtle distinctions but might offer an explanation where both the reading and graph of the sign semantically overlap.

Finally, there is one more example which could demonstrate links to the topographic uses both the Star War glyph and jom have in common. On the Palenque Initial Series Vase (Figure 3), one could read the relevant Star War passage as bolon jom kab . Such a reading resembles terms like the Yukatekan jóomkab “abismo” or jom áaktun “caverna” (Gómez Navarrete 2009:135). It is possible that we are looking at another example of the Star War glyph being used in topographic references. In this instance, possible translations may be “nine abysses”, “caves/caverns”, or simply the “9-Abyss Place”. This would resemble other such toponymic references that combine the number nine with geographical features such as “Nine Lands” (Tokovinine 2013:44-46) or “Nine Hills Place” (Stuart 2004b:5).

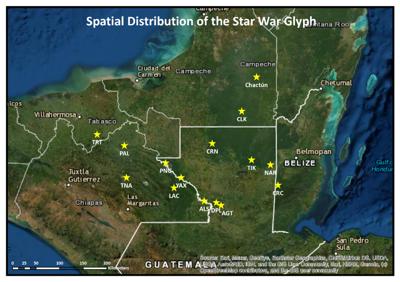

There may also be reason to doubt the likelihood of previous reading proposals such as jub . For instance, a number of differences between jub and the Star War glyph call this link into question. Aside from the fact that no direct substitution exists between the two terms, their spatial distribution is fairly different, with jub only being used in certain parts of the Maya Area whereas the Star War glyph is more widespread (see Figure 8).

|

|

|---|

Another point to consider, is that Star War events often fall on the days Ak’bal and Ix, whereas to my knowledge almost no jub event ever falls on these days (8). On top of that, the Star War glyph takes on the terms kab ch’een or ch’een as its subjects, while the jub verb does not. Moreover, certain grammatical features of the Star War glyph such as its pairing with numerical coefficients, nominalisation, and the taking of prepositions in martial contexts, are not observed with jub . Finally, the two terms also appear to differ when it comes to the moon phases on which they fall, with Star War military events primarily falling on both the waxing gibbous (7-15 days) and waning gibbous phases of the moon (16-24 days), while jub military events tend to only fall on the waxing gibbous phase (7-15 days). If jub is the reading of the Star War glyph, one would expect the two terms to exhibit very similar behaviour but that is not evident in the inscriptions.

Other terms such as hay have previously been considered as possible Star War readings, especially by researchers favouring a CVY root (Boot 1995; Kinsman n.d.). While discussing one of the Chilam Balam passages mentioned previously, Zender cited the terms bulkabal “flood” and haycabal “destrucción del mundo” as examples that might be illustrative of an incorporated kab in the Star War reading (Zender 2020:68). However, since no clear and consistent pattern of graph change is seen among Star War occurrences, the idea of kab acting as an incorporated noun seems unlikely. Examples such as the Palenque Initial Series Vase or the Star War Vase show instances where kab and kab ch’een follow star-over-earth occurrences which in turn would produce repetitive readings. From the examples available, the kab element does not appear to play any key role in the syntax of the Star War glyph and does not make predictable appearances. That being said, proposals such as hay rely on a limited number of dictionary entries, mostly restricted to Yukatek. As noted by Boot (1995), some refer to destruction, however the majority have to do with “thinning” which would be less fitting when considering all Star War occurrences.

Why would /JOM/ be a fitting reading proposal for the Star War glyph? Such a reading would fit in every single semantic context of the Star War glyph, and could provide sound explanations for all known occurrences, even the more challenging ones. There is considerable overlap between the uses of jom in Mayan languages and the Star War glyph, not only with regards to their meanings, but also in the ways they are used. A potential /JOM/ reading would cover the meanings of sinking, warfare, destruction, topography, as well as natural phenomena such as storms and deluges. Therefore, /JOM/ would constitute a good “semantic common denominator” with regards to the meanings of the Star War glyph. Such a reading proposal stands out, as it would fit visually, grammatically, thematically, semantically, and is based on a term we know was already in use during the Classic Period.

Unfortunately, the biggest problem facing this entire hypothesis, is the same one facing other Star War reading proposals, which is the lack of any syllabic spelling or phonetic complements that can confirm or disconfirm it. Hopefully future discoveries will help settle this decades-old question once and for all. Until then one can only speculate and work with the little evidence that we have so far.

References

ACADEMIA DE LAS LENGUAS MAYAS DE GUATEMALA (ALMG)

2003a Spaxti’al Slolonelal, Vocabulario Chuj: Chuj - Kaxlanh ti’, Kaxlanh ti’ - Chuj. Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala, Guatemala.

2003b Muuch’t’an Mopan, Vocabulario Mopan: Mopan - Español, Español - Mopan. Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala, Guatemala**.**

Ajpacajá Tum, Florentino, Manuel Chox Tum, Francisco Tepaz Raxulew, and Diego Guarchaj Ajtzalam

1996 Diccionario K’iche’. Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín, Guatemala.

Aldana, Gerardo

2005 Agency and the “Star War” Glyph: A Historical Reassessment of Classic Maya Astrology and Warfare. Ancient Mesoamerica 16(2):305–320.

Andrés, Domingo, Karen Dakin, José Juan, Leandro López, and Fernando Peñalosa

1996 Diccionario Akateko - Español. Ediciones Yax Te’, Rancho Palos Verdes.

Ara, Domingo de

1986 Vocabulario de lengua Tseldal según el orden de Copanabastla. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City.

Arzápalo Marín, Ramón

1987 El ritual des los Bacabes. Universidad Autómoma de México, Mexico City.

Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo

1980 Diccionario Maya: Maya - Español, Español - Maya. Ediciones Cordemex, Mérida.

Bastarrachea Manzano, Juan R., Ermilo Yah Pech, and Fidencio Briceño Chel

1998 Diccionario básico Español - Maya - Español. Maldonado Editores, Mérida.

Berlin, Brent, and Terrence Kaufman

1997 Un pequeño glosario Tzeltal de Tenejapa, Chiapas, Mexico: Tzeltal – English - Castellano, English – Tzeltal - Castellano. University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia.

Bíró, Péter

2020 A Short Note on Winte’ Nah as “House of Darts”. PARI Journal 21(1):14-16.

Bolles, David

2001 Combined Dictionary-Concordance of the Yucatecan Mayan Language. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI), Crystal River. Electronic document, http://www.famsi.org/reports/96072/index.html , accessed May 16, 2021.

Boot, Erik

1995 The ‘Star-over-shell/earth’ as Haykah ‘Destroy Villages’. Manuscript.

Bricker, Victoria Reifler, Eleuterio Poʻot Yah, and Ofelia Dzul de Poʻot

1998 A Dictionary of the Maya Language as Spoken in Hocabá, Yucatán. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Ciudad Real, Antonio de

2001 Calepino Maya de Motul , edited by René Acuña. Plaza y Valdés Editores, Mexico City.

Cowan, Marion M.

2001 Diccionario Tzotzil Huixtán. SIL International, Dallas. Electronic document, https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/58739 .

Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo

2006 A Reading for the "Earth-Star" Verb in Ancient Maya Writing. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 56. Center for Maya Research, Barnardsville.

Closs, Michael

1979 Venus in the Maya World: Glyphs, Gods and Associated Astronomical Phenomena. In Tercera Mesa Redonda de Palenque 4, edited by Merle Greene Robertson and Donnan Call Jeffers, pp. 147–165. Pre-Columbian Art Research Center, Pebble Beach.

Christenson, Allen J.

2003 K'iche' - English Dictionary and Guide to Pronunciation of the K’iche’ - Maya Alphabet. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI), Crystal Rover. Electronic

document, http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/dictionary/christenson/quidic_complete.pdf , accessed May 16, 2021.

Edmonson, Munro S.

1965 Quiche - English Dictionary. Publication 30. Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University, New Orleans.

Estrada-Belli, Francisco, and Alexandre Tokovinine

2016 A King’s Apotheosis: Iconography, Text, and Politics from a Classic Maya Temple at Holmul. Latin American Antiquity 27(2):149–168.

Fash, William L., Alexandre Tokovinine, and Barbara W. Fash

2009 The House of New Fire at Teotihuacan and its Legacy in Mesoamerica. In The Art of Urbanism: How Mesoamerican Kingdoms Represented Themselves in Architecture and Imagery, edited by William L. Fash and Leonardo López Luján, pp. 201-229. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

Feldman, Lawrence H.

2000 Pokom Maya and Their Colonial Dictionaries. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI), Crystal River. Electronic document, http://www.famsi.org/reports/97022/97022Feldman01.pdf , accessed May 17, 2021.

Furbee-Losee, Louanna

1976 The Correct Language: Tojolabal: A Grammar with Ethnographic Notes. Garland Publishing, New York.

Garay Herrera, Alejandro J.

2017 La carga del K'uhul Ajaw: Legitimidad y gobierno en el reinado de Waxaklajuun Ub'aah K'awiil de Copán (695-738 d.C.). Licenciate thesis. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala.

Gómez Navarrete, Javier Abelardo

2009 Diccionario Introductorio Español – Maya Maya – Español. Universidad de Quintana Roo, Chetumal.

Grazioso, Liwy

2002 La guerra: Religión o politica. In Religión Maya , edited by Mercedes de la Carza and Martha Ilia Nájera, pp. 217-249. Editorial Trotta, Madrid.

Gronemeyer, Sven

2014 The Conventions of Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: Being a Contribution to the Phonemic Reconstruction of Classic Mayan. PhD dissertation. La Trobe University, Melbourne.

Guenter, Stanley P.

2020 On Copán Stela 11 and the Origins of the Ill Omen of Katun 8 Ahau. In A Forest of History: The Maya After the Emergence of Divine Kingship, edited by Travis W. Stanton and M. Kathryn Brown, pp. 236-247. University Press of Colorado, Louisville.

Andrews Heath de Zapata, Dorothy

1978 Vocabulario de Mayathan, Mayan Dictionary: Maya - English, English - Maya. Área Maya, Mérida.

Helmke, Christophe

2012 Mythological Emblem Glyphs of Ancient Maya Kings. Contributions in New World Archaeology 3:91–126.

Hofling, Charles A.

2011 Mopan – Spanish - English Dictionary. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

2014 Lacandon Maya – Spanish - English Dictionary. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Hofling, Charles Andrew, and Félix Fernando Tesucún

1997 Itzaj Maya - Spanish - English Dictionary, Diccionario Maya Itzaj - Español - Inglés. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Hurley Delgaty, Alfa, and Agustín Ruíz Sánchez

1978 Diccionario Tzotzil de San Andrés con variaciones dialectales: Tzotzil - Español, Español - Tzotzil. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, Mexico City.

Kaufman, Terrence

2003 A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI), Crystal River. Electronic

document, http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/pmed.pdf , accessed May 16, 2021.

Keller, Kathryn C., and Plácido Luciano G.

1997 Diccionario Chontal de Tabasco. Serie de vocabularios y diccionarios indígenas “Mariano Silva y Aceves” 36. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, Tucson.

Kettunen, Harri, and Christophe Helmke

2005 Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs: Workshop Handbook. Wayeb.

Kinsman, Hutch J.

n.d. Tortuguero Monument 6: Part One, Tales of Destruction. In Grammar in the Script , edited by Hutch J. Kinsman. Unpublished manuscript. University Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Knowles, Susan M.

1984 A Descriptive Grammar of Chontal Maya (San Carlos Dialect). PhD dissertation. Tulane University, New Orleans.

Kremer, Hans Jürgen

2006 El barco de los muertos: Un ritual chamanístico mortuorio de los Mayas del Clásico. Ketzalcalli 1:2-25.

Kremer, Hans Jürgen, and Alexander W. Voss

1993 Naranjo: War in the Eastern Peten - A Study on War Related Expressions. Part 1: The War Glyph Expressions, 2nd Revision. Final term paper for the Advanced Seminar Tikal, Naranjo and Caracol: Alliances, Wars and Territorial Organisation by Nikolai Grube, Winter term 1991/1992. Unpublished manuscript. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn.

Laughlin, Robert M.

1975 The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of San Lorenzo Zinacantán. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology , 19. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Laughlin, Robert M., and John B. Haviland

1988 The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of Santo Domingo Zinacantán: with Grammatical Analysis and Historical Commentary. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology , 31. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Lenkersdorf, Carlos

2010 B’omak’umal kastiya-tojol’ab’al 2. Diccionario español-tojolabal, idioma mayense de Chiapas. 3rd edition. Plaza y Valdés, Mexico City.

Maldonado Andrés, Juan, Juan Ordonoez Domingo, and Juan Ortiz Domingo

1983 Diccionario de San Ildefonso Ixtahuacan, Huehuetenango. Verlag für Ethnologie, Hannover.

Michelon, Oscar

1976 Diccionario de San Francisco. Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt, Graz.

Prager, Christian

2013 Übernatürliche Akteure in der Klassischen Maya-Religion: Eine Untersuchung zu intrakultureller Variation und Stabilität am Beispiel des k'uh "Götter"-Konzepts in den religiösen Vorstellungen und Überzeugungen Klassischer Maya-Eliten (250 - 900 n.Chr.). PhD dissertation. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn.

Pérez, Juan P.

1866-1877 Diccionario de la lengua maya. Impr. Literaria de Juan F. Molina Solis, Mérida.

Pineda, Vicente

1986 Sublevaciones indígenas en Chiapas: Gramática y diccionario tzel-tal. Instituto Nacional Indigenista, Mexico City.

Reents-Budet, Dorie, Ronald L. Bishop, Jennifer T. Taschek, and Joseph W. Ball

2000 Out of the Palace Dumps: Ceramic Production and use at Buenavista Del Cayo. Ancient Mesoamerica 11:99-121.

Reents-Budet, Dorie

1994 Painting the Maya Universe: Royal Ceramics of the Classic Period. Duke University Press, Durham.

Rivera Acosta, Laura Gabriella

2018 De cuando se hicieron montaña los cráneos y mar la sangre: La guerra en el clásico maya. PhD dissertation. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City.

Rodríguez Guaján, Demetrio, Jesús Leopoldo Tzian Guantá, and José Obispo Rodríguez Guaján

1990 Ch’uticholtzij, Maya-Kaqchikel: Vocabultio Kaqchikel-Español, Español-Kaqchikel. Ediciones COCADI / Ediciones PLFM, Guatemala.

Roys, Ralph L.

1967 The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Schele, Linda, and David Freidel

1990 A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. William Morrow, New York.

Schele, Linda, and Peter Mathews

1993 Notebook for the XVIIth Maya Hieroglyphic Workshop at Texas, March 13-14, 1993. Department of Art and Art History, the College of Fine Arts, and the Institute of Latin American Studies, University of Texas at Austin, Austin.

Schumann Gálvez, Otto

1997 Introducción al maya mopán: Los Itzáes desde la época prehispánica hasta la actualidad: estudio interdisciplinario de un grupo maya. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City.

Sedat, Elizabeth R. V. de

2001 Tusq’orik Poqomchi’ - Kaxlan Q’orik. Cholsamaj, Guatemala.

Simón Morales, Erico, and Ernesto Baltazar Gutierrez.

2007 Pujb'il Yool B'a'aj - Diccionario Bilingüe Tektiteko-Español. Guatemala: Cholsamaj.

Stuart, David S.

1993 Historical Inscriptions and the Maya Collapse. In Lowland Maya Civilization in the Eighth Century A.D.: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 7th and 8th October 1989 , edited by Jeremy Sabloff and John S. Henderson, pp. 321-354. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

1995 A Study of Maya Inscriptions. PhD dissertation. Vanderbilt University, Nashville.

2000 'The Arrival of Strangers': Teotihuacan and Tollan in Classic Maya History. In Mesoamerica's Classic Heritage: From Teotihuacan to the Aztecs , edited by David Carrasco, Lindsay Jones, and Scott Sessions, pp. 465-513. University Press of Colorado, Boulder.

2004a The Paw Stone: The Place Name of Piedras Negras, Guatemala. PARI Journal 4(3):1-6.

2004b New Year Records in Classic Maya Inscriptions. PARI Journal 5(2):1-6.

2004c The Beginnings of the Copan Dynasty: A Review of the Hieroglyphic and Historical Evidence. In Understanding Early Classic Copan , edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer, pp. 215-247. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

2011 The Order of Days: The Maya World and the Truth About 2012. Harmony Books, New York.

Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan

2014-to date A Working List of Maya Hieroglyphic Signs and their Graphs. Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn. Electronic document, https://classicmayan.org , accessed June 19, 2021.

Tokovinine, Alexandre

2013 Place and Identity in Classic Maya Narratives. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

Ulrich, Matthew, and Rosemary W. Ulrich

1976 Diccionario Bilingüe Maya Mopán y Español, Español y Maya Mopán. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, Guatemala.

Wald, Robert Francis

2007 The verbal complex in classic-period Maya hieroglyphic inscriptions: Its implications for language identification and change. PhD dissertation. University of Texas at Austin, Austin.

Wagner, Elisabeth

2009 Der Untergang: Überlegungen zur Ikonographie des "Stern-über-Erde"-Logogramms in der Mayaschrift. Paper presented at the 12. Mesoamerikanistik-Tagung , Bonn.

Yoshida, Shigeto

2009 Diccionario de la conjugación de verbos en el maya yucateco actual. Graduate School of International Cultural Studies, Tohoku University, Sendai.

Zender, Marc

2020 Disaster, Deluge, and Destruction on the Star War Vase. The Mayanist (2)1:57-76.

Appendix: Dictionary Entries

Terms related to “sinking/falling/collapsing/getting a hole”

| YUK | jom | to push into an abyss | (Bolles 2001:1746) |

| YUK | jom | hundir, desfondar | (Yoshida 2009:28) |

| YUK | hom kahal | hundirse | (Michelon 1976:147) |

| YUK | hom chahal | hundirse en el lodo (los cascos de caballo) | (Michelon 1976:147) |

| YUK | joom | desfondado | (Gómez Navarrete 2009:135) |

| YUK | joom | desfondar | (Gómez Navarrete 2009:135) |

| YUK | jom | perforado | (Gómez Navarrete 2009:135) |

| YUK | hom | remove bottom | (Bricker et al. 1998:110) |

| YUK | hóom | remove bottom | (Bricker et al. 1998:110) |

| YUK | homchahal | hundirse o sumirse los pies en el lodo o atolladero | (Ciudad Real 2001:258) |

| YUK | homchek’tah | hundir o sumir el pie en cosa hueca | (Ciudad Real 2001:259) |

| YUK | homil’ahal | hundirse, ir en el hueco | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) |

| YUK | homol | hundir, desfondarse, abismar | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) |

| YUK | hoomol | hundirse al desplomarse alguna cosa hueca o cavernosa | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) |

| ITZ | jomk’ajal | hacerse hoyo (de golpe), desplomarse, get a hole (suddenly), collapse | (Hofling & Tesucún 1997:319) |

| ITZ | jomol | ahoyarse, collapse, cave in, get a hole | (Hofling & Tesucún 1997:319) |

| ITZ | joom | ahoyar, hacer hoyo, perforate | (Hofling & Tesucún 1997:319) |

| ITZ | jomik | ahoyarlo, hacerle hoyo grande, make a hole, perforate | (Hofling & Tesucún 1997:319) |

| MOP | jomca’al | hundido/a, pando/a, profundo/a | (Ulrich & Ulrich 1976:107) |

| MOP | joma’an | hundido | (ALMG 2003b:42) |

| MOP | joomi | fue hundida | (ALMG 2003b:42) |

| MOP | jomik | semi hundido | (ALMG 2003b:43) |

| MOP | jom | hundir, sink | (Hofling 2011:220) |

| MOP | joma’an | hundido | (Hofling 2011:220) |

| MOP | jomb’ol | hundrirlo, be sunk | (Hofling 2011:220) |

| MOP | jomtal | hundirse, sink | (Hofling 2011:221) |

| MOP | jomik | hundir | (Schumann Gálvez 1997:262) |

| LAC | jo’m-jo’m | derrumbado, collapsed | (Hofling 2014:159) |

| LAC | jo’man | romperlo, be broken | (Hofling 2014:159) |

| LAC | jóoman | romperse, break up | (Hofling 2014:163) |

| LAC | jóomsik | ahoyarlo, make a hole in | (Hofling 2014:163) |

| AKA | homlone | hundir | (Andrés et al. 1996:56) |

| AKA | homloi | hundirse | (Andrés et al. 1996:56) |

| CHN | hom(e(l)) | to sink, fall in | (Knowles 1984:423) |

| CHN | jome | hundirse, sumirse | (Keller & Luciano 1997:139) |

| CHN | jomesan | hundir, sumir, sumergir | (Keller & Luciano 1997:139) |

| TZE | jom | pierce it, agujerearlo | (Berlin & Kaufman 1997:26) |

| TZE | jomel | ahuecar | (Pineda 1986:401) |

| TZE | jomol | ahuecado | (Pineda 1986:401) |

| TZO | jomol | está perforado, está agujereado | (Cowan 2001:53 |

| TZO | jomol | está roto (tela) | (Cowan 2001:53 |

| TZO | jomel | hacer o cavar un hoyo, agujerear, perforar | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | jomol | roto, perforado | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | sjomemal | rompimiento | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | jomoch’tael | perforar, picar | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | jom ta ‘ut | fosa, cosa hueca | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | jomal te’ | dugout, arteza | (Laughlin & Haviland 1988:213) |

| CHJ | jom | escarpar, to dig | (ALMG 2003a:42) |

| KCH | jomojik | ahondado, hundido, hondo, deep, sunk | (Ajpacajá Tum et al. 1996:99) |

| MAM | joml | vacío:el estómago | (Maldonado Andrés et al. 1983:114) |

Topographic/Landscape-related Terms

| YUK | johm | zanja, cima, hoyo hundimiento de la tierra | (Kaufman 2003:992) |

| YUK | hom | zanja, abismo | (Michelon 1976:147) |

| YUK | jom | zanja, hoyo o barranca obscura | (Gómez Navarrete 2009:135) |

| YUK | jóomkab | abismo | (Gómez Navarrete 2009:136) |

| YUK | jom áaktun | caverna | (Gómez Navarrete 2009:135) |

| YUK | jomlil | cueva | (Gómez Navarrete 2009:135) |

| YUK | homil | la parte hundida | (Pérez 1866-1877:137) |

| YUK | jóom | hoyo, concavidad | (Bastarrachea Manzano et al. 1998:93) |

| YUK | hóom | subside (earth) | (Bricker et al. 1998:110) |

| YUK | hóomol | subsided | (Bricker et al. 1998:111) |

| YUK | hom | zanja, sima, hoya o barranca oscura, hundimiento de tierra | (Ciudad Real 2001:258) |

| YUK | hom | zanja, sima, hoya o barranca oscura, hundimiento de tierra y cabo o quebrada que dejó algún aguaducho y caverna de tierra y atolladero | (Ciudad Real 2001:258) |

| YUK | hom | abismo | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:228) |

| YUK | hom | barranco oscuro y hondo, hoyo hondo y oscuro, agujero hondo como de tuza o topo | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:228) |

| YUK | hom lu’um | zanja, foso | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:228) |

| YUK | homhom | cavernas muy desplomadas, hundimientos repetidos | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:228) |

| YUK | homil | cueva, hueco | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) |

| LAC | jo’m ru’um | tierra derrumbada, collapsed land | (Hofling 2014:159) |

| TZO | jomel | hacer o cavar un hoyo, agujerear, perforar | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | sjomal | valle | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | homal | gorge, narrow valley | (Laughlin 1975:157) |

| TZO | sjomolil | abertura, hoyo | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | jomol ch’en | cueva | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:67) |

| TZO | jom-te’ | canoa | (Delgaty & Ruíz Sánchez 1978:66) |

| TZO | hom | canoe, trough (for animals or salt manufacture) | (Laughlin 1975:157) |

| TZO | jom | embrasure, loophole, tronera | (Laughlin & Haviland 1988:213) |

| TZO | jom | boat, canoe, ship | (Laughlin & Haviland 1988:213) |

| AKA | homan | hundido (tierra) | (Andrés et al. 1996:56) |

| AKA | homkiltaj | desnivelado (tierra) | (Andrés et al. 1996:56) |

| AKA | homoni | estar bien hundido (tierra) | (Andrés et al. 1996:56) |

| TEK | jomil | agujerear, hacer uno o más agujeros en la tierra | (Morales & Guiterrez 2007:120) |

| KCHq | jom | instalación para juego de pelota maya | (Rodríguez Guaján et al. 1990:59) |

| KCH | hom | ball court | (Edmonson 1965:41) |

Destruction/violence/disruption-related Terms

| YUK | homchahal cah | perderse destruirse o hundirse el pueblo | (Ciudad Real 2001:258) |

| YUK | homah | derribar edificios, cerros, hundirse la tierra | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) |

| YUK | homol | hundirse el edificio | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:230) |

| CHN | homole | war | (Knowles 1984:423) |

| PQM | homel | desolación, calamidad, destrucción, estrago, clades, exterminación, vastitar | (Feldman 2000:116) |

| TOJ | jomi | descomponerse, destruirse, degenerar, atarantarse, confundirse, arruinarse | (Lenkersdorf 2010:274) |

| TOJ | jomo | destruir, devovar, batir, corromper, atantar, confundir, contradecirse | (Lenkersdorf 2010:273 |

| TOJ | hom-(Vw) | to ruin, to destroy, to wreck | (Furbee-Losee 1976:352) |

| TOJ | jomuman | destructor, asesino, veneno | (Lenkersdorf 2010:274) |

| TOJ | jomtala’an | tachar, asolar | (Lenkersdorf 2010:274) |

Meteorological Terms

| TZE | homel | diluvio | (Ara 1986:47) |

| TZE | hom | hacerse diluvio | (Ara 1986:47) |

| TZE | homel haal | agua grande | (Ara 1986:47) |

| YUK | homol | crecida mar o río | (Ciudad Real 2001:259) |

| YUK | hom | creciente de mar o río, marea alta | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) |

| YUK | hom kaknab | alterarse y embravecerse la mar | (Andrews Heath de Zapata 1978:258) |

| YUK | hom | el sonido de viento | (Michelon 1976:147) |

| YUK | homchahal k’ak’nab | alterarse y embravecerse la mar | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) |

| YUK | homocnac kaknab | anda la mar brava y alterada | (Ciudad Real 2001:259) |

| YUK | homoknak ik’ | viento recio y bravo que hace ruido | (Ciudad Real 2001:259) |

| YUK | homchahal ik’ | ventar muy recio, algún viento | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:229) |

| YUK | homoknakil lu’um | humedad de la tierra | (Barrera Vásquez 1980:230) |

| KCH | jomomik | sound of rushing water or wind | (Christenson 2003:46 |

| KCH | homoh | sigh (of wind in the trees) | (Edmonson 1965:41) |

| KCH | homovik | sigh (of wind in the trees) | (Edmonson 1965:41) |

| PCH | jomlik | fuerte viento, huracán | (Sedat 2001:358) |

Footnotes

-

Many of these reading proposals are unofficial or unpublished. For this reason, the years displayed here may not correspond to publications.

-

Cited in Wagner (2009).

-

Cited in Grazioso (2002: 241-242).

-

Cited in Kettunen and Helmke (2005: 72).

-

Personal Communication (2020).

-

Personal Communication (2020).

-

The Barrera Vásquez dictionary (Barrera Vásquez 1980) does not distinguish between the sounds of hache recia and hache suave. For this reason, terms were chosen that also occurred in or semantically corresponded to terms in the Calepino de Motul dictionary (Ciudad Real 2001) which does make the distinction.

-

One exception to this would be a jub event registered on Tamarindito, Hieroglyphic Stairway 2, Step 4: B1 corresponding to 9.16.9.17.14.