und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

A Ceramic Vessel of Unknown Provenance in Bonn

Research Note 1

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.15.rn001.en

Christian Prager (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Sven Gronemeyer (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn; La Trobe University, Melbourne) &

Elisabeth Wagner (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

This initial epigraphic note (1) by the members of the "Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan" project is dedicated to the text and imagery of a hitherto unpublished ceramic vessel that is on display in the Bonner Altamerika-Sammlung (BASA) at the University of Bonn (2).

Object Description

The first object from the museum's Maya collection to be described dates to the Late Classic Period (600 to 900 A.D.) and is a cylindrical, flaring-walled ceramic vessel that is currently on display in the museum. Together with other Maya artefacts, the vessel was donated to the collection in July 2012, and it bears the inventory number 4674. In the Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan project, the text has been given the number IDIOM233.

The piece, although broken in several pieces and later glued together by the former owner, is in good condition. It measures 14 cm in height, with a maximum diameter of 10 cm. The surface is covered with a buff-colored slip which serves as the background for a painting in black and red-orange, although it has suffered some loss of paint details due to slip and paint having flaked off in some areas. Although the vessel body had been restored, no restoration of the painting nor re-painting has been undertaken.

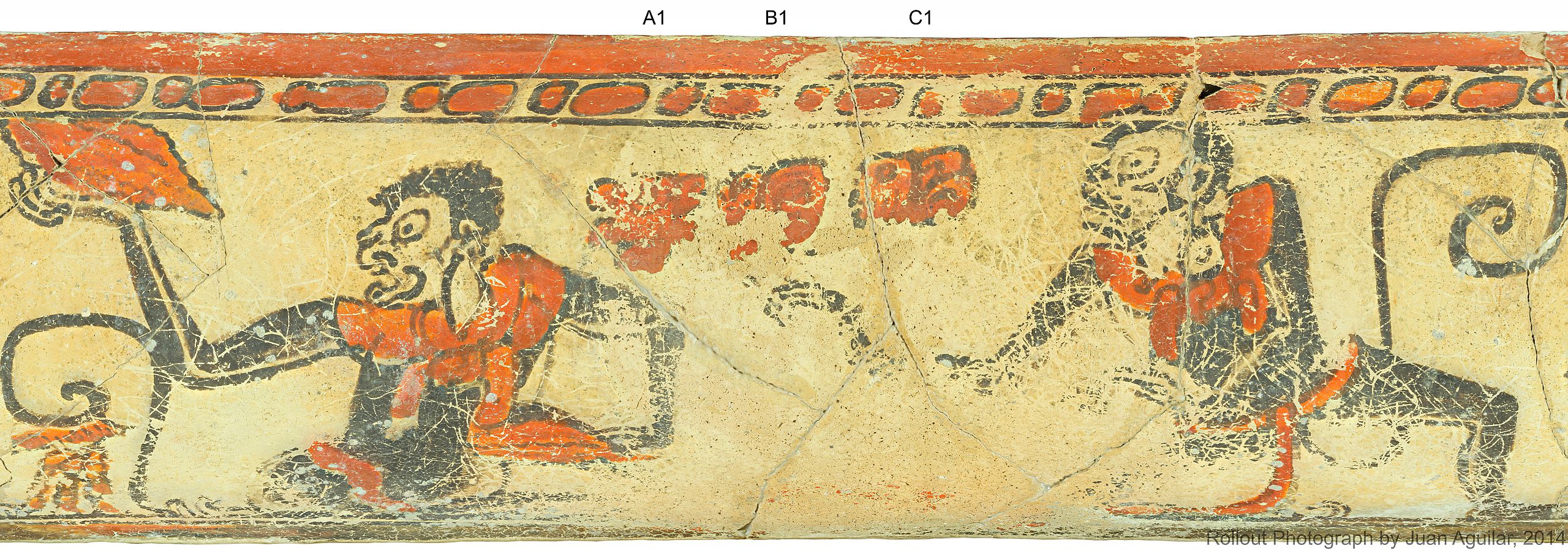

The vessel features a scene painted in red and black on a buff-coloured background that is accompanied by a short hieroglyphic text consisting of three blocks. Two narrow red bands at the top and bottom of the vessel – both delineated by black lines – constitute the frame of the painted scene. There is one black line below the red band at the top, and two parallel black lines are painted atop the bottom one. Immediately below the top band below the rim, a band of empty hieroglyphic cartouches painted in red with black contours surrounds the perimeter of the vessel. This band is framed by a thin black line, which likewise delineates the lower margin of the red band below the rim.

The sequence in which the individual components of the painted scene are discussed here is based on their visibility on the rollout photograph. The scene constitutes a depiction of two monkeys, and between them, roughly at the height of their heads, is painted a hieroglyphic inscription that consists of three blocks arranged horizontally and slanting slightly upwards from left to right. The three blocks are rendered in black and filled in with red paint. The inclination seems to be intentional, with the purpose of linking the monkeys' heads with the inscription.

Iconography

The two monkeys are depicted frontally, with their heads in profile view facing to the left. Both monkeys feature a completely black body with the inner sides of both arms and legs in a buff color. Both animals are clad with a red loincloth and a sheet of red cloth draped around their shoulders and knotted in the front. The rendering of the two monkeys' bodies is the same, but their faces appear slightly different. While the monkey on the left features toothless and short stub jaws, the one on the right clearly shows a row of teeth and an elongated lower jaw. Since both monkeys have the fur color and pattern and the thin limbs characteristic of spider monkeys, their slightly divergent facial features may show differences in age. The profile of the left monkey's face resembles renderings of elder humans' faces found elsewhere in Maya art. Therefore, it is possible that the monkeys depicted are of different ages, with the elder one on the left and a younger one on the right. Their remaining facial features are the same: a buff-colour face and a dark line around the mouth to indicate the fur around the otherwise hairless face; large, round eyes; and a short, stubby nose. Both monkeys are wearing a buff-coloured cacao tree(?) leaf or a piece of cloth as ear ornaments. The facial features of both monkeys identify them as spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi). Their costumes are characteristic of depictions of monkeys that belong to the way-category of ancient Maya supernaturals (Grube and Nahm 1994:695-697). Their loincloths identify them as males.

The monkey on the left sits cross-legged, while his tail, raised and curled with a knotted cloth-element attached to it, is visible to his left side. He holds a cacao pod in the hand of his raised right arm and another cacao pod in the hand of his lowered left arm.

The monkey on the right is shown in a half-kneeling, half-squatting position, with both arms bent and reaching out in front of his body. His raised, curled tail is visible to his right and lacks any decorative attachment. The pose of the monkey on the right may indicate that he is reaching out for and about to jump to catch one of the cacao pods held by the other monkey.

Monkeys handling cacao pods is a common theme found on numerous painted and carved ceramic vessels of the ancient Maya and reflects a typical behaviour of monkeys residing on cacao plantations (Estrada et al. 2006) who feast on the pulp of ripe cacao pods, while also spitting and defacating the cacao beans and thus dispersing the seeds for germination and growth of future cacao trees (Estrada et al. 2006:460; Dreiss & Greenhill 2008:20). This behaviour has also led some to consider spider monkeys as "bringers of cacao" (Ogata et al. 2006:87; Christopher 2013:49) (3).

A Ceramic Vessel of Unknown Provenance in Bonn

Research Note 1Epigraphy

The blocks of the hieroglyphic inscription between the two monkey figures are designated as A1, B1, and C1, respectively. With the exception of A1, all hieroglyphic blocks (i.e., B1 and C1) are clearly legible and exhibit the following signs (sign classification according to Eric Thompson, 1962):

| A1 |  |

[.] |

|---|---|---|

| B1 |  |

T743a |

| C1 |  |

T501ba T203atz’u |

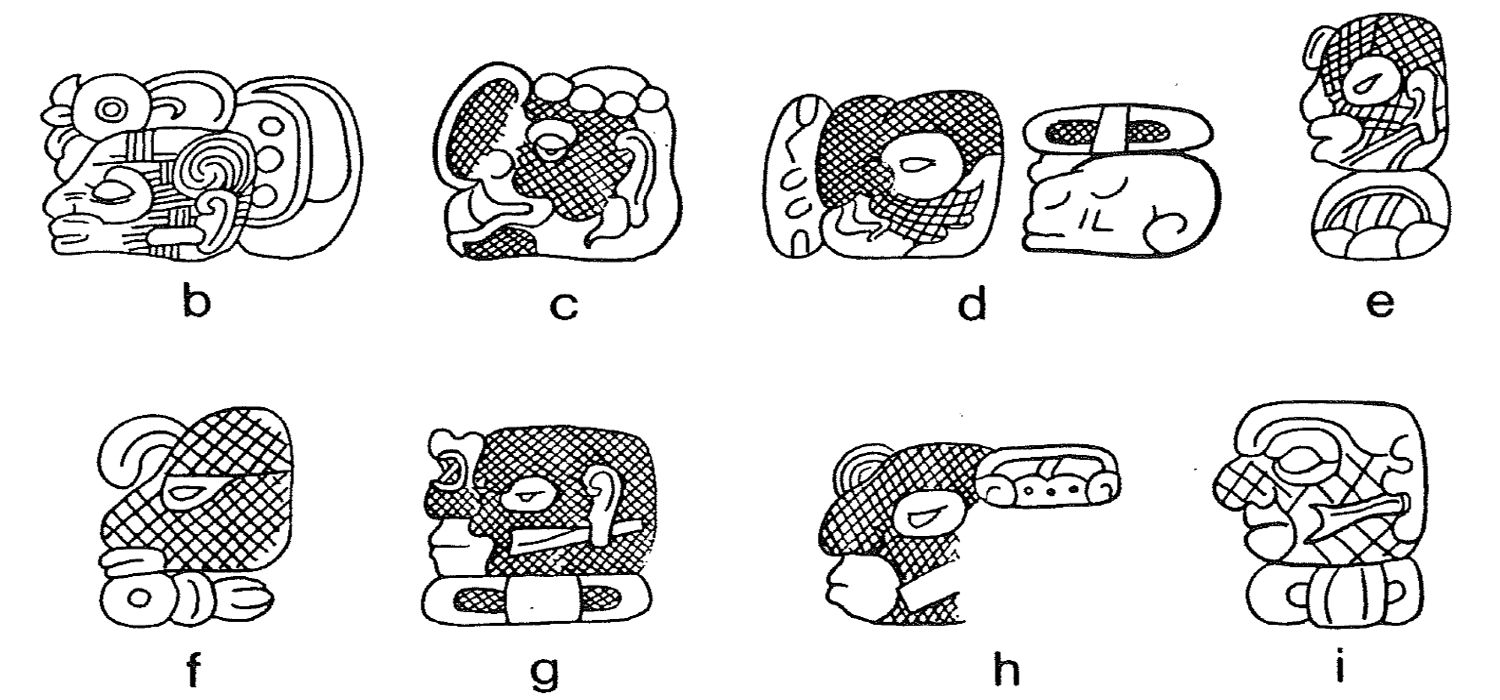

Examined in the context of the monkey images, glyph block C1 most likely represents the glyph collocation ba-tz'u, first deciphered and translated as "howler monkey" by Nikolai Grube and Werner Nahm (1994:696-697, Fig. 20). The collocation ba-tz'u corresponds to the Chol noun batz’ " howler monkey; zaraguate" (Josserand and Hopkins 1988), batz’ ‘zarahuato, mono aullador’ (Schumann 1973:76) and bats’ ‘mono’ (Aulie and Aulie 1978: 31). In Cholti, it has survived as batz ‘mono barbado’ (Morán 1695:137) or ‘mono de gueguecho’ (Morán 1695:141), and in modern Yucatec, b’àatz’ translates to ‘howler monkey’ (Bricker et al. 1998: 24). Furthermore, the meaning 'howler monkey' is attested in numerous colonial and modern Mayan languages (see Kaufman and Justeson 2003:585 or Lacadena and Wichmann 2004:138-139). However, the meaning of ba-tz'u as 'howler monkey' contradicts the depiction of the monkeys on the vessel discussed here as clearly being spider monkeys. Therefore, it can be assumed that ba-tz'u could also have been used as a generic term whose referent included various species of monkey. This idea is supported by an entry in Domingo de Ara's colonial Tzeltal dictionary in which batz simply means "monkey" (Ara 1986:249). It is also reinforced by images of monkeys on the so-called Deer-Dragon Vase (Schele 1985:61, Fig. 3; Grube and Nahm 1994:696, Fig. 20) and other ceramics (e.g. Kerr 5070), which combine the fur pattern of a spider monkey with the face of a howler monkey.

Despite the fact that some of its details have been lost, the sign in B1 can be identified as the turtle head T743 A. Grammatically, it most likely represents the agentive proclitic a[j]. As Alfonso Lacadena illustrated using the example of the ajk'uhun title, a Maya scribe could simply employ the single sign a to render the agentive proclitic aj (Lacadena 1996). The Classic Mayan collocation a-ba-tz'u most likely corresponds to the Colonial Yucatec entry hbaaɔ"mono saraguato" (Pío Perez 1898:49) and ah baaɔ"mono que llaman también saraguato" (Pío Perez 1866-1877:4).

The first hieroglyph in block A1 is partially eroded and exhibits an animal head that cannot be identified. The portrait sign displays a large and bulging nose, long lips, and a circular eye marking, and the ear tapers to a point. One of the authors (Christian Prager) proposes that this morphology is similar to the icon of the personified pa-sign that was first identified by Karl Taube as a monkey-like character (Taube 1989) (Figure 2). In his study of ritual humour, Taube explains that this simian character acted as ceremonial buffoon in Classic Maya ritual dramas (Taube 1989:377). Taube writes that "Classic Maya clowns frequently impersonate particular animals; usually this is not simply donning an animal headdress, but wearing a mask and suit-in effect, becoming the beast. In terms of shabbiness, the suit and mask of the personified pa is especially coarse, and seems to be usually made of simple grass, rough cloth, or tied rags. Aside from the masks and body suits, the dress of Classic clowns is very simple, quite unlike the elaborate feathers, beads, and complex iconographic assemblages of elite ritual dress" (Taube 1989:377).

Should this reading and identification prove correct, one could claim that this hieroglyphic text contains the name phrase of a monkey character in a ritual drama. One could further speculate that this ceramic vessel was originally deposited in the burial of a ceremonial performer who had impersonated the simian buffoon in a Classic Maya ritual drama.

References

Ara, Domingo de

1986 Vocabulario de lengua tzeldal según el orden de Copanabastla. Ed. Mario H. Ruz. Fuentes para el estudio de la cultura maya 4. Universidad Nacinal Autónoma de México, México, D.F.

Aulie, H. Wilbur, and Evelyn W. de Aulie

1978 Diccionario ch’ol-español, español-ch’ol. Serie de vocabularios y diccionarios indígenas Mariano Silva y Aceves 21. Instituto Linguistico de Verano, México, D.F.

Bricker, Victoria R., Eleuterio Po’ot Yah, Ofelia Dzul de Po’ot, and Anne S. Bradburn

1998 A Dictionary of the Maya Language as Spoken in Hocabá, Yucatán. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Christopher, Hillary

2013 Cacao’s Relationship with Mesoamerican Society. Spectrum 2013(3): 48–60.

Dienhart, John M.

1997 The Mayan Languages: A Comparative Vocabulary. Electronic edition. University of Southern Denmark, Odense.

Dreiss, Meredith L., and Sharon E. Greenhill

2008 Chocolate: Pathway to the Gods. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ.

Estrada, Alejandro, Joel Saenz, Celia Harvey, Eduardo Naranjo, David Muñoz, and Marleny Rosales-Meda

2006 Primates in Agroecosystems: Conservation Value of Some Agricultural Practices in Mesoamerican Landscapes. In New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates: Distribution, Ecology, Behavior and Conservation, edited by Alejandro Estrada, Paul Garber, Mary Pavelka, and LeAndra Luecke, pp. 437–470. Springer, New York, NY.

Gronemeyer, Sven

2014 The Orthographic Conventions of Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: Being a Contribution to the Phonemic Reconstruction of Classic Mayan. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Archaeology, La Trobe University, Melbourne.

Grube, Nikolai, and Werner Nahm

1994 A Census of Xibalba: A Complete Inventory of Way Characters on Maya Ceramics. In The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases, edited by Justin Kerr and Barbara Kerr, 4:pp. 437–470. Kerr Associates, New York, NY.

Houston, Stephen D., David S. Stuart, and John S. Robertson

1998 Disharmony in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: Linguistic Change and Continuity in Classic Society. In Anatomía de una Civilización: aproximaciones interdisciplinarias a la cultura maya, edited by Andrés Ciudad Ruiz, Yolanda Fernández, José Miguel García Campillo, Josefa Iglesia Ponce de Leon, Alfonso Lacadena García-Gallo, and Luis Sanz Castro, pp. 275–296. Publicaciones de la S.E.E.M. 4. Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas, Madrid.

Josserand, J. Kathryn, and Nicholas A. Hopkins

1988 Monosyllable Dictionary Database. In Chol (Mayan) Dictionary Database, edited by J. Kathryn Josserand and Nicholas A. Hopkins. Fascicle 11. Jaguar Tours, Del Valle, TX.

Kaufman, Terence

2003 A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI).

Lacadena García-Gallo, Alfonso

1996 A New Proposal for the Transcription of the a-k’u-na/a-k’u-hun-na Title. Mayab 10: 46–49.

Lacadena García-Gallo, Alfonso, and Søren Wichmann

2004 On the Representation of the Glottal Stop in Maya Writing. In The Linguistics of Maya Writing, edited by Søren Wichmann, pp. 100–164. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Mora-Marín, David F.

2004 Affixation Conventionalization Hypothesis: Explanation of Conventionalized Spellings in Mayan Writing. Chapel Hill, NC.

Morán, Francisco

1935 Arte y diccionario en lengua choltí; a manuscript copied from the Libro grande of fr. Pedro [sic] Moran of about 1625. Ed. William Gates. Maya Society Publication 9. The Maya Society, Baltimore.

Pérez, Juan Pío

1866 Diccionario de la lengua maya. Impr. Literaria, de Juan F. Molina Solis, Mérida.

1898 Coordinación alfabética de las voces del idioma maya que se hallan en el arte y obras del padre Fr. Pedro Beltrán de Santa Rosa, con las equivalencias castellanas que en las mismas se hallan, compuesta por J. P. Pérez. Imprenta de la Ermita, Mérida, Yucatán.

Ogata, Nisao, Arturo Gómez-Pompa, and Karl A. Taube

2006 The Domestication and Distribution of Theobroma cacao L. in the Neotropics. In Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao, edited by Cameron L. McNeil, pp. 69–89. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Schele, Linda

1985 Balan-Ahau: A Possible Reading of the Tikal Emblem Glyph and a Title at Palenque. In Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980, edited by Elizabeth P. Benson, pp. 59–65. The Palenque Round Table Series 4. The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, San Francisco, CA.

Schumann-Gálvez, Otto

1973 La lengua chol, de Tila (Chiapas). Centro de Estudios Mayas, Cuaderno 8. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Méxcio, D.F.

Taube, Karl A.

1989 Ritual Humor in Classic Maya Religion. In Word and Image in Maya Culture: Explorations in Language, Writing, and Representation, edited by William F. Hanks and Don S. Rice, pp. 351–382. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Thompson, J. Eric S.

1962 A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. The Civilization of the American Indian Series 62. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK.

Footnotes

-

This research paper abstains from indicating or reconstructing vowel complexity on the basis of supragraphematic vowel disharmony, as has been proposed in two studies (Houston, Stuart & Robertson 1998, Lacadena & Wichmann 2004). There are two main reasons for this approach: 1) although both proposals operate under similar premises, their conclusions are rather distinct; and 2) no consensus on the mechanisms of disharmonic spellings has yet been reached, resulting in alternative views on the reasons underlying the phenomenon of vowel disharmony (e.g. Kaufman 2003, Mora-Marín 2004, Gronemeyer 2014b). We neither neglect previous research nor entirely dismiss the possibility of a quantitative Classic Mayan vowel system and its orthographic indication. Before the project has collected sufficient epigraphic data and can test previous proposals against the existing evidence or formulate new hypotheses, we prefer to pursue an unprejudiced approach in terms of the epigraphic analysis and to be rather conservative, while also noting that the transcriptional spelling in one model may also vary between authors. We therefore apply a broad transliteration and a narrow transcription, but only as far as sounds can be reconstructed by methods from historical linguistics. This last point essentially concerns the aspirated vowel nucleus, as in e.g. k’a[h]k’.

-

This teaching and research collection is associated with the Department for the Anthropology of the Americas and was founded in 1948. BASA holds a strong archaeological and ethnographic collection from the Americas and also has materials from Africa, Australia/Oceania and Asia. Among its nearly 10,000 objects, this university museum owns a collection of fine Maya artefacts with hieroglyphic inscriptions and scenes that will be consecutively discussed and presented to the public in this forum.

Downloads

TWKM Research Note 1

High Resolution roll-out

Textured 3D Model

Still photographs