und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

Tz’atz’ Nah, a "New" Term in the Classic Mayan Lexicon

Research Note 2

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.15.rn002.en

Elisabeth Wagner (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn),

Sven Gronemeyer (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn; La Trobe University, Melbourne)

Christian Prager (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

The inscriptions (1) of Palenque provide us with a number of extended narrative texts that are rich sources of Classic Maya terms for various classes of objects, used both in simple descriptions and in metaphorical contexts.

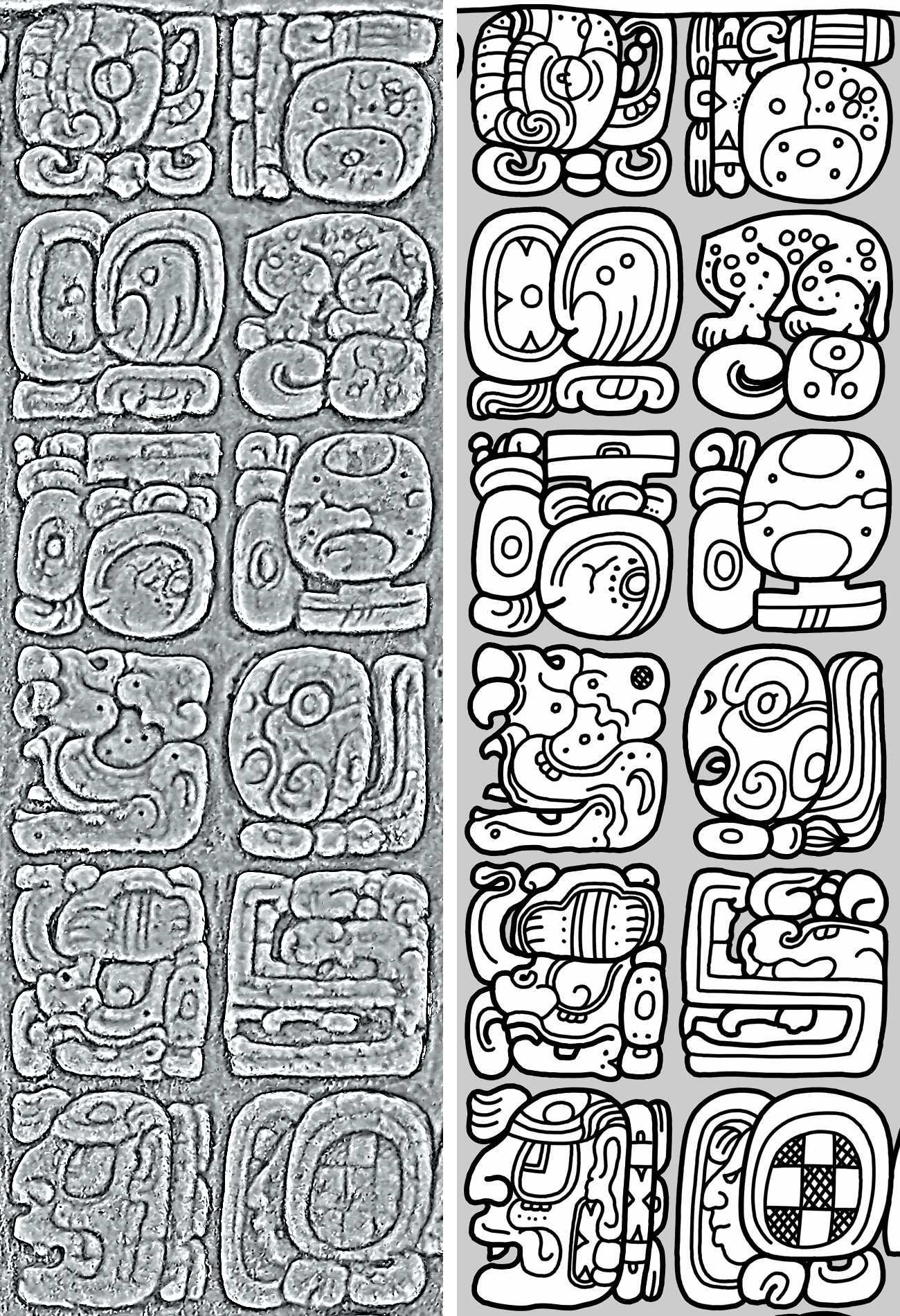

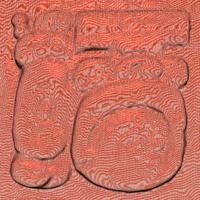

Review of a 3D-model rendered from a structured light 3D-scan of a fibre-glass cast made from Maudslay's mould of the left part of the panel from the sanctuary of the Temple of the Sun at Palenque, which is housed in the Bonner Altamerika-Sammlung (BASA) (Gronemeyer et al. 2015), revealed another term previously unknown in the Maya epigraphic record.

This term constitutes the collocation in C3 (Figure 1), which had not been completely identified in previous drawings of the inscription due to its 'squeezed' rendering by the sculptor. While the right half of C3 is clearly readable as T4 NAH T60:528 hi, nah, "house, building", the left half appeared less clear. As was faintly recognisable in the early photograph by Alfred Maudslay (Maudslay 1889-1902: pl. 87) (Figure 2a), but is clearly visible in the various renderings of the 3D scan (Figures 2b-e), the left part of block C3 is consists of the sign T366 tz'a. An instance of the "doubler", the diacritic marker for a doubled spelling of the respective sign's phonetic value (Harris 1993:ix, Stuart & Houston 1994:46, Zender 1999:102ff.), is integrated into its upper part. All in all, C3 can now be identified as 2tz'a-NAH-hi, tz'atz'+nah, which was previously unknown in the Maya epigraphic record and seems to be an architectural term, since it ends with the generic nah, "building, structure" (Stuart 1998:376) that refers to a man-made structure as a physical object. While there is a variety of names and generic architectural terms that designate actual buildings, one should not overlook the fact that such terms can also be applied metaphorically to other classes of objects in various contexts.

| a |  |

Photo of plaster cast (Maudslay 1889: pl. 87) |

| b |  |

3D scan of fibre glass replica, mesh rendering with Phong illumination for a dull surface with large highlights |

| c |  |

3D scan of fibre glass replica, mesh rendering with a vertex interference pattern to highlight level curves |

| d |  |

3D scan of fibre glass replica, mesh rendering with Lambertian radiance scaling to accentuate contours and reduce specular spots |

| e |  |

3D scan of fibre glass replica, textured mesh rendering with Phong illumination in lateral view |

Lingustic Evidence

A search for dictionary entries and translations of the root tz'atz' yielded the following entries listed in Table 1. According to Kaufman (2003: 414), ch'o(o)ch' ~ tx'o(o)tx' is a reflex of Eastern Mayan ch'o7ch', "earth". It is preserved in Q'anjobalan and has diffused into other languages, mainly into those in the so-called 'Huehuetenango Sphere' (cf. Cú Cab' et al. 2003: #4-12 for cognate sets), but also into the south-central Yukatekan branch and Q'eqchi. Together with this diffusion process, a semantic shift occurred in the term as adopted by some of the recipient languages from "earth, land" to "salty". In the Yukatekan branch, tz'atz' is phonetically related [(2)](#footnotes (Note that in several cases, the Greater Q'anjobalan and Eastern Mayan retroflex affricate /tx(')/ is cognate to the Chujean, Greater Tzeltalan, and Yukatekan alveolar /tz(')/ or alveopalatal /ch(')/ affricate (cf. Cú Cab' et al. 2003: 17-18); e.g. compare the pan-Mayan tx'i'and tz'i', "dog" (Cú Cab’ et al. 2003: #547); or more specifically AKA/POP/QAN tx'i(i) e('/h)and CHJ ch'i' eh, "canine tooth" (Cú Cab' et al. 2003: #224); CHJ chonhlab'~ CHR chojnib'~ QAN/AKA txomb'al~ POP txonhb'al, "market" (Cú Cab' et al. 2003: #71); KIC/TZU chuluuj~ KAQ/SAK/SIP chulaj~ CHJ chul~ QEQ chu'and AKA/QAN txule(j)~ POP jatxul, "urine" (Cú Cab et al. 2003: #279); or AKA/QAN tza'e(j)~ POP kotz'aand AWA xtx'aa'~ IXL txa'~ MAM tx'aj, "shit" (Cú Cab' et al. 2003: #277).)). A semantic relationship is also visible in a shift from the general meaning "earth" to "wet (fertile) earth" or "earth covered with (stale) water". Only one related cognate can be found in Ch'ol, namely the derived transitive verb tz'ajtz'an, "to wet", but this form at least provides an attestation that is geographically close to the source of the epigraphic evidence, Palenque. Also noteworthy is the semantic classifier in Akateko, but this kind of lexical class tends to be linguistically restricted to highland languages.

| YUK | ts’ats‘ | tierra en medio de cuevas donde hay agua | (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 879) |

|---|---|---|---|

| YUK | ts’ats‘ | aguada, laguneta | (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 879) |

| ITZ | tz’ätz’älb’aj | tremble, shiver | (Hofling & Tesucùn 1997: 635) |

| ITZ | tz’ätz’ämkij | sinkable | (Hofling & Tesucùn 1997: 636) |

| ITZ | tz’ätz’äpkij | sinkable, swampy | (Hofling & Tesucùn 1997: 636) |

| ITZ | ch’ooch‘ | salty | (Hofling & Tesucùn 1997: 229) |

| MOP | tz’atz‘ | pantano | (Ulrich & Ulrich 1976: 224) |

| MOP | tz’atz‘ | pantano | (Hofling 2011: 435) |

| MOP | tz’ätz’äälb’a(j) | tremble, shiver | (Hofling 2011: 436) |

| MOP | ch’ooch‘ | tiene sal, salado/a | (Ulrich & Ulrich 1976: 83) |

| MOP | ch’ooch‘ | salado | (Hofling 2011: 172) |

| CHL | ts’ajts’an | remojar | (Aulie & de Aulie 1978: 100) |

| QAN | tx’otx‘ tzx’otx‘ | la tierra | (Comunidad Lingüística Q’anjob’al 2003: 143) |

| QAN | tz’otz’ew | lodo | (de Diego Antonio et al. 2001: 322) |

| QAN | max stx’otx’nej | lo embarró | (Cú Cab‘ et al. 2003: #796) |

| POP | tx’otx‘ | tierra, terreno | (Ramírez Perez, Montejo & Díaz Hurtado 1996: 281) |

| POP | tz’otz’ew < tx'otx' | lodo | (Ramírez Perez, Montejo & Díaz Hurtado 1996: 296) |

| POP | yax tx’otx’bal | pantano | (Church & Church 1955: 67) |

| POP | tz’otz’ewlaj | lodozal, lodoso, atascadero | (Ramírez Perez, Montejo & Díaz Hurtado 1996: 296) |

| AKA | tx’ootx‘ | tierra, terreno, barro | (Andrés et al. 1996: 187) |

| AKA | tx’otx‘ | clasificador para cosas de barro o tierra | (Andrés et al. 1996: 187) |

| AKA | xyaak tx’otx‘ yiin | lo embarró | (Cú Cab‘ et al. 2003: #796) |

| AWA | tx’otx‘ | tierra | (Comunidad Lingüística Awakateka 2001: 48) |

| QEQ | ch’och‘ | tierra, terreno | (Haeserijn 1979: 147) |

| MAM | tx’otx‘ | tierra | (Comunidad Lingüística Mam 2003: 76) |

| MAM | tx’otx‘ | tierra, terreno | (Maldonado Andrés, Ordonez Domingo & Ortiz Domingo 1983: 391) |

| MAM | tx’ootx’at | trabajar bien la tierra | (Maldonado Andrés, Ordonez Domingo & Ortiz Domingo 1983: 391) |

As the cognate sets demonstrate, it is not only fruitful to consider Greater Lowland Mayan Languages (i.e. Yukatekan, Ch'olan, and Tzeltalan) in epigraphic work, but also to include Greater Q'anjobalan and even Eastern Mayan, especially those languages from highly versatile diffusion areas as the 'Huehuetenango sphere'. In the past, the relevance of these sources has been demonstrated, for example, by the -V1/__# ~ -V1w/... root transitive marker (cf. Bricker 1986: 126-128) reflected in Tojolabal and other Greater Q'anjobalan languages (3), or the absolutive marker -aj (Zender 2004: 195, 199-200) that is preserved as -aj in Ixil and Kaqchickel and as -(b)ej in Q'anjobal and Q'eqchi.

Interpretation

The lexical entries identified for tz'atz' and its cognates relate to moist or wet and muddy locales, including swamps, springs and wet caves, but also to the fertile, wet soil suitable for agriculture (4). Based on the semantic range of the root tz'atz' and its cognates in various Mayan languages (Table 1), the term tz'atz'+nah may well relate to a(n) (man-made) environment whose interior is wet, muddy, or soaked; and/or which is located near or at a spring or any other wet, muddy, or swampy place, including subterranean ones.

In the text from the Temple of the Sun, the term tz'atz'+nah forms part of an epithet of a supernatural related to GIII (Figure 1, Table 2), the local manifestation of the Sun God as a war and fire god and one of Palenque's patron gods whose mythical birth is recorded in the panel's inscription (cf. Berlin 1963, Kelley 1965, Lounsbury 1985, Stuart 2005, 2006). Before approaching the context of the term tz'atz'+nah, a short overview of the remaining name phrases shall be given.

The first name phrase that follows the birth verb in C1 is k'inich taj+way-[a]b, "Radiant Torch Dreamer" [(5)](#footnotes (By analysing syllabic and mixed spellings in a variety of contexts, Dmitri Beliaev (2004) was able to demonstrate the existence of the -ib~ -aballomorphs for the instrumental suffix in Classic Mayan, usually indicated by -biand more rarely by -baspellings. He argues that, in the present context, -abfunctions as an agentive suffix for deriving a word related to "dreamer" (Beliaev 2004: 141), in contrast to the well-known interpretation of way-ibas "dormitory". The question of semantically distinguishable allomorphs was further developed by Gronemeyer (2014b: 421-432), who identified -abas the suffix for 'animated' instrumentals (including objects considered animate, such as music instruments) - i.e. for the medium enabling an action (Gronemeyer 2014b: fn. 407) - and -ibas the 'inanimated' alloform for instruments, results, and places of action.)), which is also given as the name of a supernatural entity in an iconic rendering on the stucco-facade of an early Classic platform at Copan called Yehnal(Bell et al. 2004: Plate 2; Sedat & Lopez 2004: 94, Stuart 2004:225, Taube 2004:276, Fig. 13.7a), as well as on cache vessels from the Tikal region (Stuart 2004:225, Berjonneau & Sonnery 1985: 355). It is likely an epithet or an aspect of the supernatural named next.

The subsequent phrase k'in+ta[h]n+bolay? "Sun-Chest-'Feline'" refers to a supernatural predator feline that has been identified by Nikolai Grube and Werner Nahm (1994:687-688) on Kerr Vessel 531 [(6)](#footnotes (This feline creature features a large sun symbol covering its ventral side. On K531, the spelling is K'IN-TAN-la-T832-la-bu, and because of the -lasuffix, ta[h]nis to be understood here as "chest" and must be attributive to k’in; otherwise, the suffix cannot be explained with the preposition ta[h]n"amidst", which is derived from the noun. The name can be analysed as k’in+ta[h]n-[a]l bolay?"sun-chested feline". See Grube & Nahm (1994: 688) for the rationale behind the proposed reading bolayand Helmke & Nielsen (2009: Fig. 2) for their proposal of the value BOLfor the headless.jaguargrapheme. The regular spelling as attested in Palenque may be an underspelling, but is more likely a simple nominal compound k'in+ta[h]n+bolay. Alternatively, a different analysis of the name could apply, with a stative predicate and a prepositional phrase constituting k’in-Ø ta[h]n bolay?"it [is] the sun amidst the feline".)) as a way of the ruler(s) of the Kan-dynasty and as an aspect of the night sun. This name also occurs in similar spellings as component of nominal phrases (7), together with its occurrence in the name of one of Palenque's patron gods, may hint to some kind of link to the Kan-Dynasty not yet known from direct textual evidence.

The possible "adoption" of k'in+ta[h]n+bolay from the Kan-Dynasty and its merger with Palenque's patron god GIII may indicate that political conflicts were not only fought in the human sphere, but also had a supernatural component as "spiritual warfare", including the "capture" of supernatural entities and their incorporation into the victor's pantheon. The actual cause seem to be the former defeats of Palenque by the Kan-Dynasty under its Ruler "Scroll Serpent" in A.D. 599 and A.D. 611 (Martin 1995:109, Martin & Grube 2000:104,161, 2008:159-160) and the ultimately successful retaliations against apparent vassals of Kan. These events brought Santa Elena back under Palenque's control (Martin & Grube 2008:164-165) during the reign of K'inich Janab Pakal the Great. Later, his successor K'inich Kan Balam further restored Palenque as regional power when he fought a successful military campaign against Tonina in A.D. 687; reinstalled the ruler of Moral-Reforma, a former vassal of the Kan-Dynasty; and further incorporated La Mar and Anayte' into Palenque's political sphere (Martin & Grube 2008:170).

The other name phrase consists of three collocations (C3-C4) and includes tz'atz'+nah, followed by another term in D3, sak bak+nah "white bone(s) house", which modifies chapat "centipede" in C4. The tripartite construction mirrors the structure 'epithet/aspect + [proper name of supernatural]' of the other being. Altogether, the epithet is tz'atz'+nah sak bak+nah+chapat, which likely addresses GIII as a specific mythical centipede (whose template is most probably the Giant Central American Centipede, Scolopendra gigantea[Taube 2003]). This mythical centipede is known as a supernatural creature of the way-category under the designation as sak bak+nah+chapat (Kerr Vessel #1256) (Grube and Nahm 1994: 702, Boot 1999: 2, Kettunen & Davis 2004: 2-3). At Palenque, it is also mentioned in the inscription of Temple XIV as being the way of k'awil. But tz'atz'+nah as an attributive term in the name of the mythical centipede is only known thus far from the text discussed here. The possible referent of tz'atz'+nah will be discussed further below. The mentioned mythic centipede is associated with the destructive aspect of the Sun God as a deity of the dry season and with war, in which context it is known as huk chapat+k'inich (Boot 1999, 2005:250-256). Furthermore, it is linked to a dark and watery underworld locale known as wak+(h)a' "Centipede Water(s)", a place of both the death and the mythical rebirth of the maize god that was also the ancient name of the site El Perú (Guenter 2005:364, Matteo & Krempel 2011:145). Both building names in the epithet clearly relate to this underworldly realm, including dark and moist places, as well as those used for burial, locations that are also generally correspond to the habitat of centipedes (Lewis 1981).

The passage under discussion closes with the collocations in D4-D5, at-n-i k'a[h]k' ti'+chan? 'GIII' "'GIII became bathed in fire at sky?-mouth', which seems not to be another epithet, but another sentence with GIII as the subject that relates to an event immediately following the (re)birth of GIII. We observe two prepositional phrases, neither of which is not explicitly introduced by the preposition ti ~ ta. However, this preposition is not necessarily needed, especially when verbs of motion are involved (8). More delicate analytically is the morphology of the 'bathing' expression. While "to bath" is an instransitive verb in almost all modern Mayan languages (Wichmann 2004: 83), it has to have been a derived transitive verb at-i in Classic Mayan (cf. MacLeod 2004: 294) (9), as it is attested in the paradigm of the transitive, so-called 'secondary verbs'. A nominal root at "bath" is still attested in several Mayan languages, e.g. Ch'orti' and Tzotzil. As no ergative pronoun is visible to mark the agent, however, we nevertheless are dealing with an intransitive form in this case. Application of an inchoative suffix -an seems to be the most obvious derivational process [(10)](#footnotes (An inchoative typical for Western Ch'olan can still be found in Chontal as -ʔa(-n)/ -ʔiand -n-an/ -n-i, as well as Ch'ol as -ʔa-n/ -ʔa(i.e. incompletive/completive, cf. MacLeod 1987: fig. 15), prompting a Western Ch'olan *-a-n/ *-a(j). The existence of a -Vninchoative suffix has already been recognised by Stuart (2005: 72), but based on syntactic observations, and at present specifically on attestations of ajaw, "lord" in inscriptions ranging from Middle Classic Naranjo (Altar 1) to Late Classic Palenque (House C East Face Eaves). The origin of this suffix cannot thus be only Western Ch'olan; indeed, we can also reconstruct *-V1n~ *-infor proto-Tzeltalan (Kaufman 1972: 142), and it is likely that Eastern Cholan did not inherit the suffix from a proto-Ch'olan form.)). The original Classic Mayan -an form then innovated into -n-i in the Tabasco region beginning around 9.12.0.0.0 (Gronemeyer 2014a: 153, 2014b: 508-509), and is still preserved in Chontal (11). This assumption is also supported by the disharmonic a-ti-ni spelling: although it resembles the derived verbal stem, it cannot be a fully phonetic representation of at-an, which would presumably be spelled a-ta-ni. Instead, a-ti-ni more likely spells at-n-i, without an -an suffix.

This phrase seems to allude to a renewal or 'rebirth' of GIII by incorporating the aforementioned entity from Kan's pantheon and thus fusing it into a new, modified entity. The 'bathing' alludes to the common practice of bathing a child shortly after birth and is used here metaphorically in reference to GIII's (re)birth through the ritual of dedicating and installing a newly-created image of GIII in the temple. The "bathing in fire at sky-mouth" may relate to the image of GIII set up in the Temple of the Sun - either a statue and/or the central image on the tablet – that is illuminated by the sun on the horizon at dawn and thus literally bathed in the fire or heat of the sunlight [(12)](#footnotes (The compound ti'+chan, literally "sky-mouth" or "sky-edge", can be interpreted as a term for "horizon" or "mountain ridge", i.e. where the sky touches the earth. Compare to YUK chi' ka'an, "cordillera de sierra" (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 97) and similar metaphors, e.g. chi' kab, "costa de mar" or chi' ch'e'n, "borde de pozo" (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 91), or the lexicalised chik'in, "el poniente u occidente, donde se pone el sol" (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 99). Conceptions of an edge or boundary of two entities as being a 'mouth' are common in Mayan languages, e.g. ITZ chi' ja', "orilla del lago", chi' k'ab'-naab', "costa del mar" (Hofling & Tesucún 1997: 208); CHR ti' e witzir, "mountain pass" (Wisdom 1950: 672); CHN u ti' otot, "puerta de la casa" (Keller & Luciano 1997: 239); TZE ti' q'uinal, "(la) orilla del monte" (Slocum & Gerdel 1971: 188); TZO tiˀ k'ok', "fireside" (Laughlin 1975: 337).)). Observations by Alonso Mendez, Edwin Barnhart, Christopher Powell and Carol Karasik (2005) have revealed that a statue standing in the centre of the Temple of the Sun would be fully illuminated by the rising sun on the day of summer solstice (June 21) (Mendez et al. 2005: 14-15, Fig. 16) and on the day of the nadir passage (November 9), when a broad beam of light enters the temple's central doorway (Mendez et al. 2005:19-20, Figs. 24-27). Further, it is worth noting that the latter date of the nadir passage falls just shortly after the day of GIII's mythical birth on October 25 (2360 B.C.).

| C1 | SIH-ya-ja si[y]-aj-Ø N:gift-INTRZV.INCH-3s.ABS born was |

| D1-D2 | K’INICH-TAJ-WAY°bi K’IN-ni-TAN-na BOL?-yu-la k’in-ich taj+way-[a]b k’in+ta[h]n+bolay? N:sun-ADJVZ N:torch VI:sleep-NMLZ.INSTR N:sun+N:chest+N:feline ‚radiant torch-dreamer‘, [the] ’sun-chest-feline‘ [and] |

| C3-C4 | 2tz’a-NAH-hi SAK-BAK-NAH CHAPAT tz’atz’+nah sak bak+nah+chapat N:pool+N:house ADJ:white N:bone+N:house+N:centipede ‚pool-house‘, [the] ‚white bone-house centipede‘ |

| D4-D6 | a-ti-ni K’AK‘ TI‘-CHAN K’INICH ?-?-wa at-n-i-Ø k’a[h]k‘ ti’+chan k’in-ich ?+? N:bath-INTRZV.INCH-COMPL-3s.ABS N:fire N:mouth+N:sky N:sun-ADJVZ N:?+N:? [the] ‚radiant ?‘ [i.e. GIII] became bathed [in] fire [at] ’sky-mouth‘ |

Is there an actual tz'atz' nah at Palenque?

As in other Maya cities, most of the (mythical) place- and building names recorded at Palenque constitute a mythic/symbolic landscape projected on the local topography and the man-made structures therein, in the form of building groups, plazas, and single buildings, that constitute the ancient city (Stuart 2005, 2006: 88-93). This also includes the Temple of the Sun, whose ancient name k'inich pas+kab "Radiant Rise Earth" is recorded in the dedication inscription on its balustrades (Stuart 2005, 2006: 158). This toponym probably refers to the still-visible outcrop of whitish limestone rock that was integrated in unaltered form into the western side of the Temple of the Sun's pyramidal base, and which appears "radiant" when lit by the rising sun. Therefore, we assume that tz'atz'+nah and sak bak+nah in GIII's epithet refer not to the Temple of the Sun itself, but instead more generally to the habitat of GIII as mythical centipede. But this does not exclude the possibility that actual locations or structures in the city of Palenque or even nearby the shrine of GIII were perceived as such, and thus may have been addressed in the epithet. Thus the question arises: What actual structure at Palenque could have been denominated tz'atz'+nah?

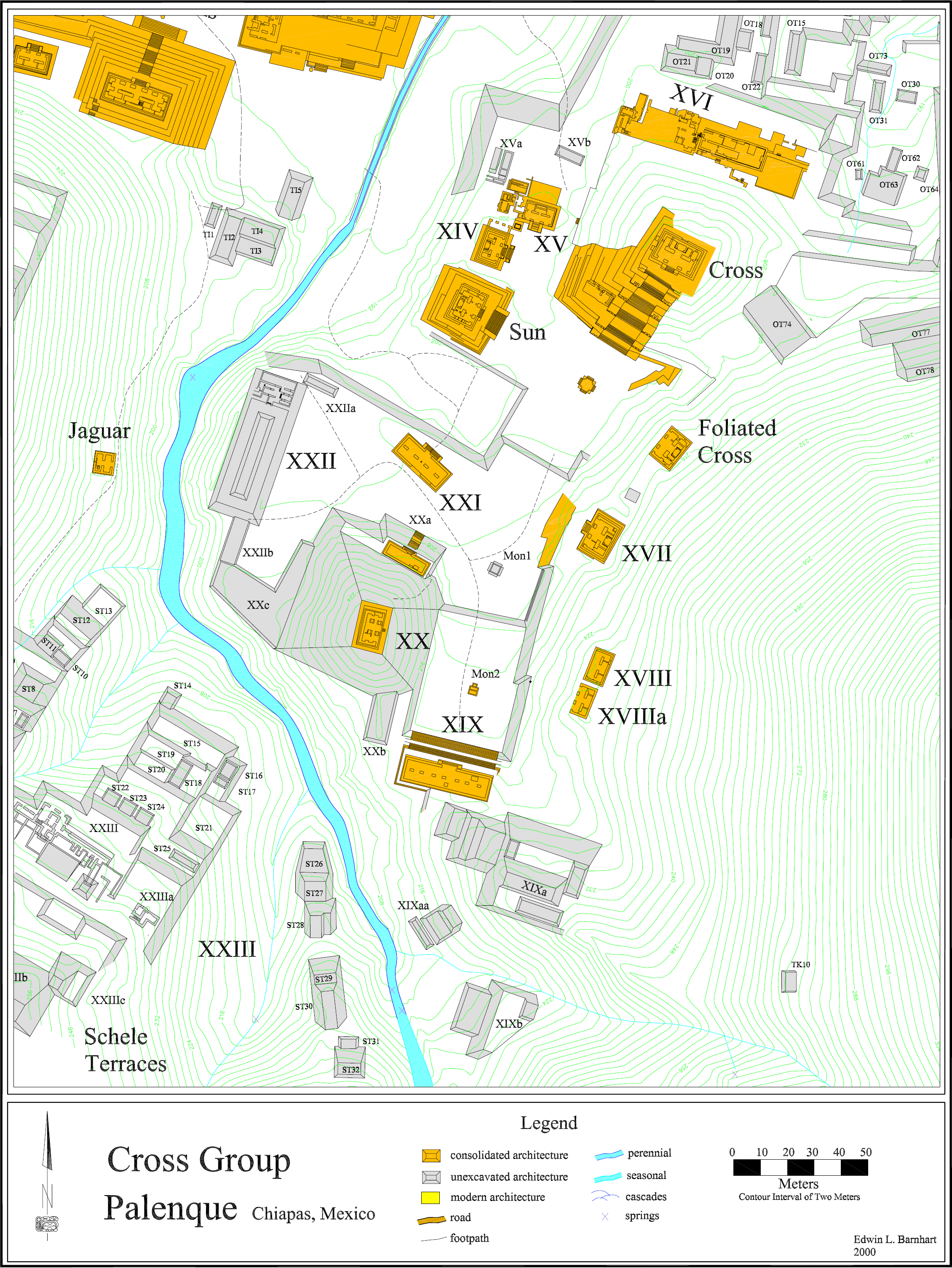

The area covered by the urban core of Palenque is divided by a number of perennial and seasonal streams that originate from springs within the urban settlement and farther uphill (French 2002, 2009, Barnhart 2001). The all-over importance of bodies of water and their management at the site of Palenque has most recently been discussed in several studies by Kirk French (2002, 2009, 2014) and is clearly reflected in the toponym lakam ha', "Large/Big Water(s)", which refers to the centre of the site.

Palenque's hydraulic structures not only served practical functions by providing drinking water and water for sanitary installations, but also played an important role in the symbolic and ritual landscape of Palenque. As is known from numerous Maya texts and images, bodies of water play an important role as places of origin in Classic Maya mythology. In this context, Palenque in particular has a detailed mythological record in which watery places play a crucial role (cf. Kelley 1965, Stuart & Houston 1994: 30, 69, Stuart 2005, 2006). Such places are mentioned in the texts and depicted in the accompanying pictorial programmes.

The ancient urbanonym lakam ha' (Stuart & Houston 1994: 30-31) clearly relates to the dominating body of water and the biggest of Palenque's streams which is today known as Otulum (Stuart 2006: 92), but seemingly refers to the palace acropolis and adjacent area (Gronemeyer in press). Furthermore, this and other streams have been managed by the Maya in various ways by means of man-made constructions like open channels, vaulted aqueducts and pools (French 2002, 2009, French et al. 2012, 2013), of which the channel and aqueduct of the Otulum running below the Cross Group and past the Palace are the most prominent.

Importantly, the Otulum stream which passes the Cross Group to the west, enters the artificial walled and partly vaulted channel at the height of the northern side of Temple of the Sun (Barnhart 2001: 12, Fig. 2.3; Stuart 2006: 87) (Figure 3). The positioning of the location at which the Otulum stream enters the artificial channel in relation to the Temple of the Sun's northern margin may not be accidental. Instead, it may be an alignment intended to symbolically link them to important locations as parts of Palenque's symbolic landscape.: It can be observed that the entry of the open channel, the centre of both the Temples of the Sun and the Foliated Cross, and the central platform in the Cross Group Plaza together define a straight NW-SE-axis roughly aligned with the top shrine on Mirador mountain (see Barnhart 2001: 8, Map 2.1), the latter most probably being identical with Palenque's prime sacred mountain, y-e[h]m-al k'uk' lakam witz "Descent of the Quetzal (from) the Big Mountain" (Stuart 2006:92, Gronemeyer in press). The Otulum was obviously the most important spring in Palenque's sacred landscape and is probably linked with the mythic watery location matwil, the mythic birthplace of all three patron gods (Stuart & Stuart 2008: 211). These observations, together with the previously discussed meanings of the root tz'atz' in combination with nah to designate a man-made structure or building, may provide an indication of the structure to which tz'atz'+nah is referring.

Basing on the previous observations, we furthermore propose that tz'atz'+nah may refer to an actual structure at Palenque. An appropriate candidate would be a hydraulic structure that is closely associated with the Temple of the Sun and the spring of the Otulum stream, namely the channel and the vaulted aqueduct controlling the course of the Otulum stream along the Cross Group and the Palace.

References

Domingo, Andrés, Karen Dakin, José Juan Leandro López, and Fernando Peñalosa

1996 Diccionario Akateko-Español. Ediciones Yax Te’, Rancho Palos Verdes.

Aulie, H. Wilbur, and Evelyn W. de Aulie

1978 Diccionario ch’ol-español, español-ch’ol. Serie de vocabularios y diccionarios indígenas Mariano Silva y Aceves 21. Instituto Linguistico de Verano, México, D.F.

Barnhart, Edwin L.

2001 The Palenque Mapping Project: Settlement and Urbanism at an Ancient Maya City. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Graduate School, University of Texas, Austin, TX.

Barrera Vásquez, Alfredo

1980 Diccionario Maya. Maya-Español, Español-Maya. Ediciones Cordemex, Mérida.

Beliaev, Dmitri

2004 Wayaab’ Title in Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions. On the Problem of Religious Specialization in Classic Maya Society. In Continuity and Change: Maya Religious Practices in Temporal Perspective, edited by Daniel Graña-Behrens, Nikolai Grube, Christian M. Prager, Frauke Sachse, Stefanie Teufel, and Elisabeth Wagner, pp. 121–130. Acta Mesoamericana 14. Anton Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

Bell, Ellen E., Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer (editors).

2004 Understanding Early Classic Copan. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Boot, Erik

1999 Of Serpents and Centipedes: The Epithet Wuk Chapaht Chan K’inich Ahaw (Notes on Maya Hieroglyphic Writing, 25). Unpublished manuscript. Rijswijk.

2005 Continuity and Change in Text and Image at Chichén Itzá, Yucatán, Mexico: A Study of the Inscriptions, Iconography, and Architecture at a Late Classic to Early Postclassic Maya Site. CNWS Publications 135. CNWS Publications, Leiden.

Berjonneau, Gérald, and Jean-Louis Sonnery (editors).

1985 Rediscovered Masterpieces of Mesoamerica: Mexico-Guatemala-Honduras. Editions Arts, Bologna.

Berlin, Heinrich

1963 The Palenque Triad. Journal de la Société des Américanistes 52(1): 91–99.

Bricker, Victoria R.

1986 A Grammar of Mayan Hieroglyphs. Middle American Research Institute Publication 56. Tulane University: Middle American Research Institute, New Orleans, LA.

Comunidad Lingüística Awakateka

2001 Tqan qayool: vocabulario awakateko. Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala, Guatemala.

Comunidad Lingüística Mam

2003 Pujb’il yol mam: vocabulario mam. Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala, Guatemala.

Comunidad Lingüística Q’anjob’al

2003 Jit’il q’anej yet q’anjob’al: vocabulario q’anjob’al. Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala, Guatemala.

Cú Cab, Carlos Humberto, Juan Carlos Sacb’a Caal, Juventino Pérez Alonzo, María Beatriz Par Sapón, Marina Magdalena Ajcac Cruz, Matilde Eustaquio Caal Ical, Nikte’ María Juliana Siis Ib’ooy, Pakal José Obispo Rodríguez Guaján, Saqijix Candelaria López Ixcoy, Teodoro Cirilio Ixcoy Herrera, Walter Rolando Pérez Morales, and Waykan José Gonzalo Benito Pérez

2003 Maya choltzij: vocabulario comparativo de los idiomas mayas de Guatemala. Cholsamaj, Guatemala.

de Diego Antonio, Diego, Adán Francisco Pascual, Nicolas de Nicolas Pedro, Carmelino Fernando Gonzalez, and Santiago Juan Matias

2001 Diccionario del idioma q’anjob’al. Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín, Antigua.

Fox, James A. 1978 Proto-Mayan Accent, Morpheme Structure Conditions, and Velar Innovations. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Linguistics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

French, Kirk D.

2002 Creating Space through Water Management at the Classic Maya Site of Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH.

2009 The Hydroarchaeological Approach: Understanding the Ancient Maya Impact on the Palenque Watershed. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

2014 Palenque Pool Project. http://palenquepoolproject.blogspot.com/

French, Kirk D., Christopher J. Duffy, and Gopal Bhatt

2012 The Hydroarchaeological Method: A Case Study at the Maya Site of Palenque. Latin American Antiquity 23(1): 29–50.

2013 Urban Hydrology and Hydraulic Engineering at the Classic Maya Site of Palenque. Water History Journal 5(1): 43–69.

Gronemeyer, Sven

in press The Linguistics of Toponymy in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. In Places of Power and Memory in Mesoamerica’s Past and Present: How Toponyms, Landscapes and Boundaries Shape History and Remembrance. Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut, Berlin.

2014a E pluribus unum: Embracing Vernacular Influences in a Classic Mayan Scribal Tradition. In A Celebration of the Life and Work of Pierre Robert Colas, edited by Christophe Helmke and Frauke Sachse, pp. 147–162. Acta Mesoamericana 27. Anton Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

2014b The Orthographic Conventions of Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: Being a Contribution to the Phonemic Reconstruction of Classic Mayan. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Archaeology, La Trobe University, Melbourne.

Gronemeyer, Sven, Christian M. Prager, and Elisabeth Wagner

2015 Evaluating the Digital Documentation Process from a 3D Scan to a Drawing. Vol. 2. Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya Working Paper. Nordrhein-Westfälische Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Künste & Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Bonn.

Grube, Nikolai

2004 The Orthographic Distinction between Velar and Glottal Spirants in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. In The Linguistics of Maya Writing, edited by Søren Wichmann, pp. 61–81. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Grube, Nikolai, and Werner Nahm

1994 A Census of Xibalba: A Complete Inventory of Way Characters on Maya Ceramics. In The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases, edited by Justin Kerr and Barbara Kerr, 4:pp. 437–470. Kerr Associates, New York, NY.

Guenter, Stanley P.

2005 Informe Preliminar de la Epigrafía de El Perú. In Proyecto Arqueológico El Perú-Waka’: informe no. 2, temporada 2004, edited by Héctor L. Escobedo and David A. Freidel. Instituto de Antropología e Historia de Guatemala, Guatemala. http://www.mesoweb.com/resources/informes/Waka2004.html

Haeserijn V., Estéban

1979 Diccionario k’ekchi’ español. Piedra Santa, Guatemala.

Harris, John F.

1993 New and Recent Maya Hieroglyph Readings. The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Helmke, Christophe, and Jesper Nielsen

2009 Hidden Identity & Power in Ancient Mesoamerica: Supernatural Alter Egos as Personified Diseases. Acta Americana 17(2): 49–98.

Hofling, Charles A.

2011 Mopan Maya - Spanish - English dictionary / diccionario Maya Mopan - Español - Ingles. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Hofling, Charles A., and Francisco Fernando Tesucún

1997 Itzaj Maya - Spanish - English Dictionary. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Houston, Stephen D., David S. Stuart, and John S. Robertson

1998 Disharmony in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: Linguistic Change and Continuity in Classic Society. In Anatomía de una Civilización: aproximaciones interdisciplinarias a la cultura maya, edited by Andrés Ciudad Ruiz, Yolanda Fernández, José Miguel García Campillo, Josefa Iglesia Ponce de Leon, Alfonso Lacadena García-Gallo, and Luis Sanz Castro, pp. 275–296. Publicaciones de la S.E.E.M. 4. Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas, Madrid.

Kaufman, Terence

1972 El proto-tzeltal-tzotzil: fonología comparada y diccionario reconstruido. Centro de Estudios Mayas, Cuaderno 5. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Méxcio, D.F.

2003 A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI). http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/pmed.pdf

Keller, Kathryn, and Plácido Luciano

1997 Diccionario chontal de Tabasco (mayense). Serie de vocabularios y diccionarios indígenas Mariano Silva y Aceves 36. Summer Institute of Linguistics, Tucson, AZ.

Kelley, David H.

1965 The Birth of the Gods at Palenque. Estudios de Cultura Maya 5: 93–134.

Kerr, Justin n.d. Maya Vase Database. http://research.mayavase.com/

Kettunen, Harri, and Bon V. Davis II

2004 Snakes, Centipedes, Snakepedes, and Centiserpents: Conflation of Liminal Species in Maya Iconography and Ethnozoology. Vol. 9. Wayeb Notes. Wayeb: European Association of Mayanists, Bruxelles.

MacLeod, Barbara

1987 An Epigrapher’s Annotated Index to Cholan and Yucatecan Verb Morphology. University of Missouri Monographs in Anthropology 9. University of Missouri, Columbia, MO.

2004 A World in a Grain of Sand: Transitive Perfect Verbs in the Classic Maya Script. In The Linguistics of Maya Writing, edited by Søren Wichmann, pp. 291–325. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Laughlin, Robert M.

1975 The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of San Lorenzo Zinacantán. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology 19. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Lewis, John G. E. 1981 The Biology of Centipedes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Maldonado Andrés, Juan, Juan Ordonoez Domingo, and Juan Ortiz Domingo

1983 Diccionario de San Ildefonso Ixtahuacan, Huehuetenango. Verlag für Ethnologie, Hannover.

Lacadena García-Gallo, Alfonso, and Søren Wichmann

2004 On the Representation of the Glottal Stop in Maya Writing. In The Linguistics of Maya Writing, edited by Søren Wichmann, pp. 100–164. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

Lounsbury, Floyd G.

1985 The Identities of the Mythological Figures in the Cross Group Inscriptions of Palenque. In Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980, edited by Elizabeth P. Benson, pp. 45–58. The Palenque Round Table Series 4. The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, San Francisco, CA.

Martin, Simon

1997 Nuevos datos epigráficos sobre la guerra maya del clásico. In La Guerra entre los Antiguos Mayas, edited by Silvia Trejo, pp. 105–124. Memoria de la Primera Mesa Redonda de Palenque. Instituto Nacional de Anthropología e Historia, Méxcio, D.F.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai K. Grube

2000 Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. Thames & Hudson, London.

2008 Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. 2nd ed. Thames & Hudson, London.

Matteo, Sebastián F. C., and Guido Krempel

2011 Un vaso cilíndrico polícromo de la región de Rio Azul, Guatemala, en una colección privada. Mexicon 33(6): 142–146.

Maudslay, Alfred P.

1889 Biologia Centrali-Americana, or, Contributions to the Knowledge of the Fauna and Flora of Mexico and Central America. Archaeology. R. H. Porter and Dulau & co., London.

Mendez, Alonso, Edwin L. Barnhart, Christopher Powell, and Carol Karasik

2005 Astronomical Observations from the Temple of the Sun. Archaeoastronomy (Journal of Astronomy in Culture) 19: 44–73.

Mora-Marín, David F.

2004 Affixation Conventionalization Hypothesis: Explanation of Conventionalized Spellings in Mayan Writing. Chapel Hill, NC.

Ramírez Perez, José, Andrés Montejo, and Baltazar Díaz Hurtado

1996 Diccionario Jakalteko, Jakaltenango, Huehuetenango. Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín, Antigua.

Sedat, David W., and Fernando Lopez

2004 Intial Stages in the Formation of the Copan Acropolis. In Understanding Early Classic Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer, pp. 85–99. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Slocum, Marianna, and Florencia Gerdel

1971 Vocabulario tzeltal de Bachajón. Serie de vocabularios y diccionarios indígenas Mariano Silva y Aceves 13. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, Méxcio, D.F.

Stuart, David S.

1998 The Fire Enters His House: Architecture and Ritual in Classic Maya Texts. In Function and Meaning in Classic Maya Architecture, edited by Stephen D. Houston, pp. 373–425. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

2004 The Beginnings of the Copan Dynasty: A Review of the Hieroglyphic and Historical Evidence. In Understanding Early Classic Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer. University Of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology And Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA.

2005 The Inscriptions from Temple XIX at Palenque: A Commentary. The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, San Francisco, CA.

2006 Sourcebook for the 30th Maya Hieroglyphic Forum at Texas. Department of Art and Art History, the College of Fine Arts, and the Institute of Latin American Studies, Austin.

Stuart, David S., and Stephen Houston

1994 Classic Maya Place Names. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology 33. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

Stuart, David S., and George E. Stuart

2008 Palenque: Eternal City of the Maya. Thames & Hudson, London.

Taube, Karl A.

2003 Maws of Heaven and Hell: The Symbolism of the Centipede and Serpent in Classic Maya Religion. In Antropología de la eternidad: la muerte en la cultura maya, edited by Andrés Ciudad Ruiz, Mario Humberto Ruz, and Josefa Iglesia Ponce de Leon, pp. 405–442. Publicaciones de la S.E.E.M. 7. Sociedad Española de Estudios Mayas, Madrid.

2004 Structure 10L-16 and its Early Classic Antecedents: Fire and the Evocation and Resurrection of K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’. In Understanding Early Classic Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer, pp. 265–295. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

Ulrich, E. Matthew & Rosemary Dixon de Ulrich

1976 Diccionario Maya Mopan – Español, Español – Maya Mopan. Instituto Linguistico Verano, Guatemala City.

Wichmann, Søren

2004 The Names of Some Major Classic Maya Gods. In Continuity and Change: Maya Religious Practices in Temporal Perspective, edited by Daniel Graña-Behrens, Nikolai Grube, Christian M. Prager, Frauke Sachse, Stefanie Teufel, and Elisabeth Wagner, pp. 77–86. Acta Mesoamericana 14. Anton Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

Wisdom, Charles

1950 Materials on the Chorti Language. Vol. 28. icrofilm Collection of Manuscripts on Middle American Cultural Anthropology. University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Zender, Marc

2004 On the Morphology of Intimate Possession in Mayan Languages and Classic Mayan Glyphic Nouns. In The Linguistics of Maya Writing, edited by Søren Wichmann, pp. 195–209. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, UT.

2014 Diacritical Marks and Underspelling in the Classic Maya Script: Implications for Decipherment. Unpublished M.A. Thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary, Calgary.

Footnotes

-

This research paper abstains from indicating or reconstructing vowel complexity on the basis of supragraphematic vowel disharmony, as has been proposed in two studies (Houston, Stuart & Robertson 1998, Lacadena & Wichmann 2004). There are two main reasons for this approach: 1) although both proposals operate under similar premises, their conclusions are rather distinct; and 2) no consensus on the mechanisms of disharmonic spellings has yet been reached, resulting in alternative views on the reasons underlying the phenomenon of vowel disharmony (e.g. Kaufman 2003, Mora-Marín 2004, Gronemeyer 2014b). We neither neglect previous research nor entirely dismiss the possibility of a quantitative Classic Mayan vowel system and its orthographic indication. Before the project has collected sufficient epigraphic data and can test previous proposals against the existing evidence or formulate new hypotheses, we prefer to pursue an unprejudiced approach in terms of the epigraphic analysis and to be rather conservative, while also noting that the transcriptional spelling in one model may also vary between authors. We therefore apply a broad transliteration and a narrow transcription, but only as far as sounds can be reconstructed by methods from historical linguistics. This last point essentially concerns the aspirated vowel nucleus, as in e.g. k'a[h]k'.

-

Note that in several cases, the Greater Q'anjobalan and Eastern Mayan retroflex affricate /tx(')/ is cognate to the Chujean, Greater Tzeltalan, and Yukatekan alveolar /tz(')/ or alveopalatal /ch(')/ affricate (cf. Cú Cab' et al. 2003: 17-18); e.g. compare the pan-Mayan tx'i' and tz'i', "dog" (Cú Cab’ et al. 2003: #547); or more specifically AKA/POP/QAN tx'i(i) e('/h) and CHJ ch'i' eh, "canine tooth" (Cú Cab' et al. 2003: #224); CHJ chonhlab'~ CHR chojnib'~ QAN/AKA txomb'al~ POP txonhb'al, "market" (Cú Cab' et al. 2003: #71); KIC/TZU chuluuj~ KAQ/SAK/SIP chulaj~ CHJ chul~ QEQ chu' and AKA/QAN txule(j)~ POP jatxul, "urine" (Cú Cab et al. 2003: #279); or AKA/QAN tza'e(j)~ POP kotz'a and AWA xtx'aa'~ IXL txa'~ MAM tx'aj, "shit" (Cú Cab' et al. 2003: #277).

-

For a morphophonemic characterization of the Greater Q'anjobalan branch and discussion of its implications for the Ch'olan branch and Classic Mayan, see Gronemeyer (2014b: 143, 149-153).

-

As an aside, the phonetic origin of tz'atz' may be onomatopoetic, imitating the sound of the steps when walking over muddy or wet ground.

-

By analysing syllabic and mixed spellings in a variety of contexts, Dmitri Beliaev (2004) was able to demonstrate the existence of the -ib~ -ab allomorphs for the instrumental suffix in Classic Mayan, usually indicated by -bi and more rarely by -ba spellings. He argues that, in the present context, -ab functions as an agentive suffix for deriving a word related to "dreamer" (Beliaev 2004: 141), in contrast to the well-known interpretation of way-ib as "dormitory". The question of semantically distinguishable allomorphs was further developed by Gronemeyer (2014b: 421-432), who identified -ab as the suffix for 'animated' instrumentals (including objects considered animate, such as music instruments) - i.e. for the medium enabling an action (Gronemeyer 2014b: fn. 407) - and -ib as the 'inanimated' alloform for instruments, results, and places of action.

-

This feline creature features a large sun symbol covering its ventral side. On K531, the spelling is K'IN-TAN-la- T832**-la-bu**, and because of the -la suffix, ta[h]n is to be understood here as "chest" and must be attributive to k’in; otherwise, the suffix cannot be explained with the preposition ta[h]n"amidst", which is derived from the noun. The name can be analysed as k’in+ta[h]n-[a]l bolay?"sun-chested feline". See Grube & Nahm (1994: 688) for the rationale behind the proposed reading bolay and Helmke & Nielsen (2009: Fig. 2) for their proposal of the value BOL for the headless.jaguargrapheme. The regular spelling as attested in Palenque may be an underspelling, but is more likely a simple nominal compound k'in+ta[h]n+bolay. Alternatively, a different analysis of the name could apply, with a stative predicate and a prepositional phrase constituting k’in-Ø ta[h]n bolay?"it [is] the sun amidst the feline".

-

For example, its use at Tikal (Stela 3, C3-D3), Yaxchilan (Stela 18, C1-B2) and Ek' Balam (Miscellaneous Text 7, B13-B14).

-

For example, compare the texts on Kerr 1226, D3-E4 with e[h]m[-i] chan itzam yej and the Palenque Tablet of the Cross, D7-D8 with e[h]m[-i] ta chan jun ye-nal cha[h]k. Also note the och[-i] ti ha' and och[-i] ta ha' references in the Dresden Codex on pages 61, B12 and 70, D13, respectively. These expressions resemble the well-known death expression, which, although once termed 'intransitive compounds' (Grube 2004: 74-75), are more likely cases of an unwritten, and possibly even unspoken, preposition (Gronemeyer 2014b: 415-416).

-

It is derived with the Ch'olan applicative suffix -i < proto-Mayan *-in, and is also reconstructed as such in proto-Mayan as *át-iVn/ *at-í:n(Fox 1978: 107).

-

An inchoative typical for Western Ch'olan can still be found in Chontal as -ʔa(-n)/ -ʔi and -n-an/ -n-i, as well as Ch'ol as -ʔa-n/ -ʔa(i.e. incompletive/completive, cf. MacLeod 1987: fig. 15), prompting a Western Ch'olan *-a-n/ **-a(j)*. The existence of a -Vn inchoative suffix has already been recognised by Stuart (2005: 72), but based on syntactic observations, and at present specifically on attestations of ajaw, "lord" in inscriptions ranging from Middle Classic Naranjo (Altar 1) to Late Classic Palenque (House C East Face Eaves). The origin of this suffix cannot thus be only Western Ch'olan; indeed, we can also reconstruct *-V1n~ *-in for proto-Tzeltalan (Kaufman 1972: 142), and it is likely that Eastern Cholan did not inherit the suffix from a proto-Ch'olan form.

-

The suffix with its typical spelling -ni then spread eastwards (such as the intransitive positional -wan as well). The few attested cases outside Palenque suggest a temporal and spatial distribution that included Tamarindito and Naranjo in 9.13, Tikal in 9.15, and Copan and Seibal in 9.16.

-

The compound ti'+chan, literally "sky-mouth" or "sky-edge", can be interpreted as a term for "horizon" or "mountain ridge", i.e. where the sky touches the earth. Compare to YUK chi' ka'an, "cordillera de sierra" (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 97) and similar metaphors, e.g. chi' kab, "costa de mar" or chi' ch'e'n, "borde de pozo" (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 91), or the lexicalised chik'in, "el poniente u occidente, donde se pone el sol" (Barrera Vásquez 1980: 99). Conceptions of an edge or boundary of two entities as being a 'mouth' are common in Mayan languages, e.g. ITZ chi' ja', "orilla del lago", chi' k'ab'-naab', "costa del mar" (Hofling & Tesucún 1997: 208); CHR ti' e witzir, "mountain pass" (Wisdom 1950: 672); CHN u ti' otot, "puerta de la casa" (Keller & Luciano 1997: 239); TZE ti' q'uinal, "(la) orilla del monte" (Slocum & Gerdel 1971: 188); TZO tiˀ k'ok', "fireside" (Laughlin 1975: 337).

Downloads

PAL TS left (rendering)

PAL TS left (drawing)

TWKM Research Note 2