und Wörterbuch

des Klassischen Maya

A Possible Mention of the “Xukalnaah” Emblem Title on Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3

Research Note 21

DOI: https://doi.org/10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.21.rn021.en

Elisabeth Wagner (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn)

Introduction

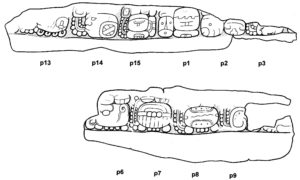

During the 2002 season of the long-term archaeological survey of southern Campeche led by Ivan Šprajc a fragmented circular monument was discovered (Šprajc 2003:14-17; Šprajc and Flores Esquivel 2008:26, 29-30; Juarez Cossío and Baker Pedroza 2008:141-142 ). Its inscription records a long list of emblem glyphs, after which its site of discovery, formerly named after the land lot Zapote Bobal in the ejido Ley de Fomento Agropecuario where it is located, was aptly renamed as “Altar de los Reyes” (Šprajc 2003:10; Šprajc and Flores Esquivel 2008:26, Grube 2008:179). The monument itself was designated as Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3 (Šprajc and Flores Esquivel 2008:29, Grube 2008:179).

The altar was found badly shattered – probably intentionally destroyed - in the center of the plaza in the West Acropolis of the mentioned site (Šprajc 2003:14; Juarez Cossío and Baker Pedroza 2008:141, Figs. 6.11-6.12; Grube 2008:180). The larger fragments feature a well preserved part of an inscription which originally encircled the entire perimeter of the lateral surface of the Altar 3. A large part of it could be re-assembled; however, a considerable part of the inscription is lost, thus leaving several inscribed fragments without an exact fit into the original text (Šprajc and Flores Esquivel 2008:30, Fig. 4.18; Grube 2008:180).

Altar 3 and the Thirteen Divine Kings

The first studies on the inscription of Altar 3 were conducted by Nikolai Grube who identified most of the still preserved emblems as those of major kingdoms throughout the Maya Lowlands (Grube 2003; 2004:122; 2008:180-182) (Figure 1). Unfortunately, only less than half of the presumed thirteen emblems are still preserved to be clearly identifiable. In the order of their listing these include: Calakmul (p6), Tikal (p7), Palenque (p8), Altun Ha (p9), […], Edzna (p14), and Motul de San José (p15) (Grube 2003:35-37; 2004:122; 2008:180-182). The emblem glyphs in p3, p10, and p13 are too damaged to be clearly identified.

Even though the remains of Altar 3 lack an inscribed date but based on the similarity of Altar 3’s sculptural style with that of Altar de los Reyes, Stela 1, which commemorates the half-K’atun event (tahn lamaw) 9.18.10.0.0 10 Ajaw 8 Sak, Nikolai Grube regards these two monuments as contemporaneous (Grube 2003:37; 2008:182, 231).

|

|

The caption on the top side of the altar was identified by Nikolai Grube as k’uhul kab, uxlajuun kab? , “sacred land(s), thirteen lands(?)” (Grube 2003:34; 2004:122; 2008:180). Alternatively, Alexandre Tokovinine (2008:139, 255-256; 2013:45, 106) has proposed reading the second part of the caption as uxlajuun tzuk , “thirteen divisions”.

Based on this caption, Nikolai Grube concluded that the list of emblem titles on the side of the altar originally comprised thirteen dynasties associated with thirteen different places, and initially he regarded this list as a model and political panorama of the “Mundo Maya” from the perspective of the monument’s patron(s) at the time when Altar 3 was commissioned (Grube 2003:37; 2005:100; 2008:182; Šprajc and Flores Esquivel 2008:28). In several studies the emblem list of Altar 3 was further discussed with respect to various aspects of socio-political, territorial and symbolical organization of the ancient Maya (Grube 2005:100; Wagner 2006:158, Šprajc and Grube 2008:275; Tokovinine 2008:255-260; 2013:45,106-108, 123; Helmke and Kupprath 2017:119; Martin 2020:148-149, 343). The super-ordinate entity defined by the thirteen emblem titles on Altar 3 has been regarded as rather symbolical than political, representing “an ideational landscape divided in space and time between thirteen royal dynasties and possibly between thirteen deities ” (Tokovinine 2008:260; 2013:108). This thirteen-part entity might be associated with the uxlajuun tzuk known from numerous texts from the Maya Lowlands (Tokovinine 2008:257; 2013:106), an entity first identified by Dmitri Beliaev that comprises people from various dynasties carrying the epitheton uxlajuun tzuk in their nominal phrases (Beliaev 2000).

In addition to the long known quadripartite entities attested on Copan, Stela A and on Seibal, Stela 10, and Tikal, MT 42 (cf. Barthel 1968; Marcus 1973; 1976; Šprajc 2003:15; Tokovinine 2008:260; 2013:87-89; Martin 2020:149), the inscription of Altar 3 adds another cosmographic model to the written record (cf. Šprajc and Grube 2008:275). This model of cosmological order provides the structure of a primordial landscape (cf. Helmke and Kupprath 2017:119). It is associated with thirteen dynasties that “constitute a kind of macroregional landscape, but a landscape of people and not of territories” (Tokovinine 2013:123). Further, this thirteen-part cosmographic model has been linked by various authors to the spatio-temporal concept known as “K’atun Wheel” attested from both Late Postclassic and early colonial sources, whereby the latter associate representations of rulers with the Ajaw day names of K’atuns (cf. Taube 1988; Houston et al. 2006:95; Tokovinine 2008:260; 2013:108; Martin 2020:149). Simon Martin (2020:149, 343) concludes that Altar 3 does not represent an actual scheme of political order, but a symbolic arrangement of kingships as spatio-temporal cosmic divisions in a ritual circuit representing an idealized scheme, employing the most powerful kingdoms of the Maya region at the time of Altar 3’s commission.

The title K’uh Xukalnaah Ajaw on Altar 3

Reviewing Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3, Fragment 2 (3), a small fragment which could not be fitted with the remainder of Altar 3’s fragments of the perimetrical inscription, reveals the remains of another two emblem glyphs (Šprajc and Flores Esquivel 2008:30, Fig. 4.18; Figure 2), designated provisionally as Blocks pX1 and pX2 (4). The emblem glyph on the right (pX2) cannot be identified since only the lower part of its prefix Sign 32, K’UH , k’uh, remains. The one to the left (pX1), however, has lost its K’UH - prefix, but still features the lower half of its toponymic element with enough details preserved to provide clues on the identity of the kingdom represented by this emblem title.

|

|

Even though the upper part of the toponymic element is broken off, its lower part still allows identifying at least two distinct graphs: those of either Signs 756, 1523, or 1539 and Graph 4vb of Sign 4 (cf. Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan 2014-to date) (7). Among the emblems attested in the Maya inscriptional corpus, these graphs occur together only in the toponym commonly spelled 756/1523/1539-25-178-4, yielding SUTZ’ / tz’i /xu-ka-la-NAH. The presence of Graph 4vb clearly excludes the other known emblem titles known from other inscriptions in southern Campeche that contain one of the bat head-shaped graphs (cf. Grube 2005; 2008; Martin 2005; Cases and Lacadena 2015:378,379; Valencia and Esparza 2018), including that of Copan as in the reference to that site’s 13th king, Waxaklajuun U Baah K’awiil, at El Palmar (cf. Tsukamoto 2014; Tsukamoto and Esparza 2015; Valencia and Esparza 2018:51-54).

The ambiguous use of Signs 756, 1523 and 1539 (8) in the attested spellings of the logograph SUTZ’ (Landa 1566) and the syllables xu (Grube 1989) and tz’i (Stuart 1987) yields three possible readings of the toponym discussed here. The first is the most widely accepted one, Xukalnaah (9), which has been translated as “cornered house” (Biro 2011a:122), based on the root xuk , “corner, side”, that is attested in various Mayan languages (cf. Kaufman 2003:342). The second, Tz’ikalnaah , has been listed by Alexandre Tokovinine (cf. Tokovinine 2013) as an alternative reading for the toponym, in addition to Xukalnaah . Another possibility would be reading the toponym as Sutz’kalnaah . Notably, Graph 756 is predominantly used to spell the Xukalnaah toponym. Graph 756st, the bat-head with its distinct “ak’bal elements” on its neck to indicate dark and glossy fur, is prominently used to spell the logograph SUTZ’ . The bat heads of Graphs 1523st and 1539st to spell xu , and tz’i respectively, usually lack the “ak’bal -element” in their neck area. Although there is sometimes confusion and no clear distinction in spellings with the various “bat graphs”, the preferred use of Graph 756st to spell the Xukalnaah-toponym by different scribes and at different times makes one wonder about a reading SUTZ’-ka-la-NAH , sutz’-kal-naah , Sutz’kalnaah.

However, due to the ambiguous use of the graphs of Signs 756, 1523, 1539, the possibility that they represent different bat species (cf. Lopes and Davletshin 2003:5; Boot 2009), the different phonetic values they represent, and the therefore yet unclear semantics of the toponym, none of the possible readings can be preferred so far. But for the sake of simplicity the most widely accepted reading, Xukalnaah is used in the present note.

The Toponym Xukalnaah and Related Titles

The toponym Xukalnaah occurs in titles mostly carried as a second emblem title by the rulers of Bonamapak and Lacanha, but also by rulers and secondary nobles from various other kingdoms in the Selva Lacandona. It forms part of a title of origin (cf. Stuart and Houston 1994:33-42), namely Aj Xukalnaah , “he from Xukalnaah”, and of the kingly titles Xukalnaah Ajaw , and K’uh Xukulnaah Ajaw respectively (cf. Biro 2016:142). All are carried by individuals identified as originating from Xukalnaah or recorded as members of a dynasty that claimed a place named Xukalnaah as its place of origin. Most common is the title Xukalnaah Ajaw . At Bonampak the Xukalnaah emblem title occurs as the second one of two emblem titles, following the first one, K’uh Ak’e Ajaw (cf. Biro 2011a:120, note 16). The emblem title K’uh Xukalnaah Ajaw is only attested in late inscriptions at Bonampak commissioned by Yajaw Chan Muwaan II, beginning with Stela 1 dedicated on 9.17.10.0.0 12 Ajaw 8 Pax (December 2, 780 AD Gregorian).

The titles containing the toponym Xukalnaah are attested in a number of inscriptions from the Selva Lacandona and the Usumacinta region such as Bonampak, Lacanha, Ojo de Agua, Yaxchilan, Piedras Negras, and various unprovenanced monuments (cf. Beliaev and Safranov 2004; 2009; Biro 2011a; 2011b; 2012:55-57) (cf. Table 1) (10) (11). The titles containing this toponym have been proposed in earlier studies as the original emblem glyph of either Lacanha (e.g. Mathews 1980, Beliaev and Safronov 2004, cited in Biro 2011a:289; Tokovinine 2013:82) or Bonampak (Sachse 1996). While Peter Biro sees no clear evidence at which site the Xukalnaah -dynasty originally settled and originated from (Biro 2016:143), Alexandre Tokovinine (2013:82) does not rule out Lacanha as the place of origin of this dynasty.

The title Xukalnaah Ajaw is carried by a number of kings of small kingdoms in the Selva Lacandona, whose nominal phrases additionally contain specific titles of origin that are associated with at least five places, including Usijwitz (Bonampak), Lacanha and other not yet securely located sites like Bubulha’ (Ojos de Agua?), Saklakal , and the “Knot Hair Site” (Nuevo Jalisco?) (cf. Beliaev and Safronov 2004; 2009; Bíró 2011:121; 2016:142; Tokovinine 2013:82-83, Table 7, Fig. 47).

A review of the various attested spellings of the Xukalnaah emblem titles reveals that the arrangement of the graphs representing the components of the toponymic element - 756st-25st/738bv -178st/178bl/178br-4vb- is not uniform but varies considerably (cf. Biro 2011a:117, note 14; 2011b:55; 2016:142), depending on the space available or the individual preferences of the respective scribe and sculptor who designed the hieroglyphic block containing that title (Table 1).

When comparing the assumed K’uh Xukalnaah Ajaw emblem with the still completely preserved other emblems on Altar 3, it becomes clear that the small element to the left of the naah -subfix is not part of the prefixed Sign 32, K’UH , but still part of the toponym. Although this element may be too damaged to clearly identify a certain graph, comparison with other examples of the Xukalnaah emblem glyph reveals that the location in the glyph block to the bottom of the bat-head Graph 756st of Sign 756, xu / tz’i, is occupied - besides Graph 4vb of Sign 4, NAH - either by Graph 25st of the Sign 25, ka, and/or Graphs 178bl or 178br of Sign 178, la. A narrow border, as it is visible on the right side of this small element, does not occur in any renderings of Graph 178, but in those of Graph 25st. The height of the bat-head of Graph 756 is well visible by the incurving of this graph on its upper right side. The space above Graph 756 was occupied by the now broken off Graph 168bt of Sign 168, AJAW, as in the other emblem glyphs on Altar 3. From this composition of the hieroglyphic block, it can be assumed that a variant of Graph 178 was somehow infixed into or fused with Graph 756st. The placement of Graph 178st as infix within Graph 756st is the most likely - either in the forehead, on the vertex of the bat-head, or in the eye. In sum, the spelling of the Xukalnaah emblem on Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3 may be reconstructed as *32vl.[168bt:[756st°178st]:[25st.4vb]].

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

To conclude, with K’uh Xukalnaah Ajaw, the representative of another component of the Late to Terminal Classic super-ordinate entity k’uh kab, uxlajuun kab?, as recorded on Altar 3 of Altar de los Reyes (cf. Grube 2003:34, 37; 2005:100; 2008:180-182) could be identified. This emblem title represents the Divine King(s) of both a supernatural place and its manifestation in the actual landscape, intimately tied with a kingdom as a regional socio-political unit in the Western Maya Lowlands. The latter was governed by members of a dynasty claiming its origin and descent from a place named Xukalnaah.

Thus, the emblem title K’uh Xukalnaah Ajaw, with the dynasty and kingdom represented by it, fills another gap in the list of dynasties that represented the “seed thrones of the Chatahnwinik ” (u-saak?/mook?/xaak? (13) -tz’amil chatahn-winik ) (cf. Grube 2003:36-37; 2008:180-182, Martin 2020:148).

Further, the late date of Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3 - 9.18.10.0.0 10 Ajaw 8 Sak - as proposed by Nikolai Grube (2003:37; 2008:182) fits very well into the late time frame of the K’uh Xukalnaah Ajaw mentions in the late texts at Bonampak commissioned by Yajaw Chan Muwaan II who was enthroned on 9.17.5.8.9 6 Muluc 17 Yaxk'in and probably died around 9.18.0.0.0, and was succeeded by probably the first of his three sons, Chooj, who acceded on 9.18.0.3.4 10 Kan 2 Kayab (cf. Houston 2012:168-171).

Worth to note is that at the time when Yajaw Chan Muwaan II governed the entity comprising the dynasties of Ak’e and Xukalnaah, this entity was still a subordinate of Yaxchilan and that dynasty’s ally by marriage, since Yajaw Chan Muwaan II’s wife, Ix Unen Bahlam, was a member of Yaxchilan’s ruling dynasty (cf. Mathews 1980:61, 64, 67). Further indicators for this socio-political relation are joint war campaigns against the “Knot Hair Site” by Yajaw Chan Muwaan II’s father, Aj Sak Teles, and later against Sak Tz’i by Yajaw Chan Muwaan II himself (Mathews 1980:67), the fact that Yajaw Chan Muwaan II’s monuments were carved by sculptors from Yaxchilan’s workshops, and finally that Yaxchilan’s then ruler Itzamnaaj Bahlam IV oversaw the accession of Yajaw Chan Muwaan II’s successor (cf. Miller 1995:62, Martin and Grube 2008:136-137).

Considering this socio-political background of the Ak’e-Xukalnaah dynasty, and the later mention of the Xukalnaah-dynasty as a prominent one on Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3, at around 9.18.10.0.0, there seems to have occurred a significant change of its socio-political status, from originally being a part of a conglomerate of dynasties and subordinate of Yaxchilan - at least until the end of Yajaw Chan Muwaan II’s reign, to an eventually independent political entity under the leadership of the Xukalnaah dynasty at a later point in time. This change seems to have occurred shortly before or after the death of Itzamnaaj Bahlam IV, probably around 9.18.10.0.0, and certainly after 9.18.9.10.10, the last date on that kings last known monument, Yaxchilan, Hieroglyphic Stairway 5 (cf. Mathews 1988:286; 2006-2015). Unfortunately no dated explicit records of any events that might have led to this change are known so far.

Worth to note and perhaps a hint to the Xukalnaah dynasty claiming and eventually gaining increased importance is Caption II-31 naming the personage facing Yajaw Chan Muwaan (Caption II-32) from the left in the top center of the mural in Room 2. This man is stated as umam keleem, “grandfather, ancestor of the young strong man/men” (cf. Houston 2009:169; 2012:163, 169, Fig. 14; Miller and Brittenham 2013:76, Fig. 127) and carries the emblem title K’uh Xukalnaah Ajaw. The expression umam keleem seems to express his relation to Yajaw Chan Muwaan II’s possible sons (cf. Houston 2012:169-171) – who are stated as ch’ok, but also carry Xukalnaah emblem titles, whereby only the first two sons, Chooj and Yaxun? Bahlam are stated as K’uh Xukalnaah Ajaw, while the youngest, Aj Bahlam, is mentioned as Xukalnaah Ajaw only (cf. Miller and Brittenham 2013:89, Tab. 4, 90, Tab. 5).

Although the personal name of the person stated as grandfather/ancestor is partly damaged, he is not Aj Sak Teles, who originates from Xukalnaah (Aj Xukalnaah) (cf. LAC Pan. 1:L6). Aj Sak Teles is stated on Bonampak, Stela 2 as the father of Yajaw Chan Muwaan II and thus would be the actual paternal grandfather of the three mentioned princes. Instead of being eventually some kind of a master or overseer of particularly the two oldest sons as battle-proven “young strong men” (keleem), the person named in caption II-31 who originates from the “Knot Hair Site” (Aj “Knot Hair Site”) might be a more distant or indirect ancestor from another line - from the “Knot Hair Site” - of the Xukalnaah dynasty. Until no further evidence about the identity of this personage comes to light, one might speculate that he might be not only a distant ancestor, but perhaps the founder of the Xukalnaah polity.

Besides Yajaw Chan Muwaan II in the center and his heir, Chooj (caption II-33) (cf. Houston 2012: 169-171), on the right, the man on the left also wears a royal jaguar fur cape. Due to their identical costume, royal titles and superior roles, their prominent position in the top center of the entire scene, the pose and orientation, these royal personages comprise basically a three-figure group within the assembly of nobles and warriors. However, to this group is added a forth identically dressed individual on the right, the assumed younger brother of the heir, Yaxun? Bahlam. However, he stands very close behind his older brother; the two figures slightly overlap and almost form a unit. In sum, this grouping of four figures represents three royal generations. Worth to note is also that the ancestral personage on the left seems to offer a tiny (jade) bead to Yajaw Chan Muwaan II (Miller and Brittenham 2013:108). Besides being a precious object from the spoils of war, the single bead might represent a symbol for passing the power and right to rule from the ancestor (founder?) to his successors, since jade beads have been identified as symbolic seeds (cf. Taube 2010).

Considering the respective dynastic position of these personages, ancestor, current and future king, this image depicting three generations clearly transports the idea of dynastic succession and continuity, linking the ancestral past with the present and future. The image of an ancestral ruler on the left facing his successor(s) to his right, and the handing over of an object from ancestor to successor(s) are familiar themes in ancient Maya art when a ruler’s descent and dynastic affiliation needs to be stressed to legitimize rule, as e.g. in the case of Yax Pasaj Chan Yopaat and his predecessors at Copan (cf. Taube 2004:268).

This in mind, that “scene within a scene” in the mural of Room 2 stresses very clearly the dynastic continuity of specifically the Xukalnaah dynasty, and eventually pointing to its striving for eventual independence and importance which – if the identification of the emblem on Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3 is correct – finally led those who commissioned the mentioned altar to regard it as one of thirteen important dynasties.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Ivan Šprajc who has provided high-resolution detail photographs of Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3 for our project, without which the identification of the Xukalnaah emblem glyph would not have been possible. Further, I would like to thank Nikolai Grube, Guido Krempel, Christian Prager, and Iván Šprajc for their useful comments and suggestions on an earlier draft of this note, including a drawing of the Chicago Altar by Guido Krempel of which a detail, Block 9 with the title Xukalnaah Ajaw, is reproduced here in Table 1 (#16).

References

Barthel, Thomas

1968 El complejo “emblema”. Estudios de Cultura Maya 7:159-193. DOI:10.19130/IIFL.ECM.1968.7.700.

Beliaev, Dmitri

2000 Wuk Tsuk and Oxlahun Tsuk: Naranjo and Tikal in the Late Classic. In The Sacred and the Profane: Architecture and Identity in the Maya Lowlands , edited by Pierre Robert Colas, Kai Delvendahl, Marcus Kuhnert, and Annette Schubart, pp. 63-81. Verlag Anton Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

Beliaev, Dmitri, and Alexander Safronov

2004 Ak’e y Xukalnah: istoriya y politicheskaya geografia gosudarstv maya Verhney usumacinti. Electronic Document. https://istina.msu.ru/download/7112185/1kcZfk:EV18zBE4wmds8FWXmTGhFNepwVc/.

2009 Saktz’i’, Ak’e and Xukalnaah: Reinterpreting the Political Geography of the Upper Usumacinta Region. Paper presented at the 14th European Maya Conference: Maya Political Relations and Strategies, Cracow, November 13–14, 2009.

Beliaev, Dmitri, and Sergei Vepretskii

2018 Los monumentos de Itsimte (Peten, Guatemala): Nuevos datos e interpretaciones. Arqueología Iberoamericana 38:3-13

Biro, Peter

2005 Sak Tz'i' in the Classic Period Hieroglyphic Inscriptions. Electronic document. http://www.mesoweb.com/articles/biro/SakTzi.pdf

2007 Las piedras labradas 2, 4 y 5 de Bonampak y los reyes de Xukalnah en el siglo VII. Estudios de Cultura Maya 29:31-61. DOI:10.19130/IIFL.ECM.2007.29.110.

2011a The Classic Maya Western Region: A History. BAR International Series 2308. Archaeopress, Oxford. DOI:10.30861/9781407308913.

2011b Classic Maya Politics in the Western Maya Region (I): Ajawil/Ajawlel and Ch’e’n. Estudios de Cultura Maya 38:41-73. DOI:10.19130/iifl.ecm.2011.38.49.

2012 Politics in the Western Maya Region (II): Emblem Glyphs. Estudios de Cultura Maya 39:31-66. DOI:10.19130/IIFL.ECM.2012.39.58.

2016 Emblem Glyphs in Classic Maya Inscriptions: From Single to Double Ones as a Means of Place of Origin, Memory and Diaspora. In Places of Power and Memory in Mesoamerica's Past and Present: How Sites, Toponyms and Landscapes Shape History and Remembrance, edited by Daniel Graña-Behrens, pp. 123-158. Estudios Indiana 9. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin.

Boot, Erik

2009 The Bat Sign in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing: Some Notes and Suggestions, Based on Examples on Late Classic Ceramics. Electronic Document. http://www.mayavase.com/boot_bat.pdf.

Cases, Ignacio, and Alfonso Lacadena

2015 Operación III.5: Estudios Epigráficos, Temporada 2014. In Proyecto Petén-Norte Naachtún 2010-2014: Informe final de la Quinta Temporada de Campo 2014, edited by Phillip Nondédéo, Julien Hiquet, Dominique Michelet, Julien Sion, and Lilian Garrido, pp. 371-384. Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris; Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centro-Americanos, Guatemala.

Graham, Ian

1982 Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions 3(3): Yaxchilan. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

Gronemeyer, Sven

2019 Abstraction through the Merger of Iconic Elements in Forming New Allographs: The Logogram 539 <WAY>. Electronic Document. Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya, Research Note 12. Electronic Document. DOI:10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.19.rn012.en.

Grube, Nikolai

1989 Bird Jaguar´s Bird. Letter dated October 28, 1989.

2003 Epigraphic Analysis of Altar 3 of Altar de los Reyes. In Archaeological Reconnaissance in Southeastern Campeche, México: 2002 Field Season Report, edited by Ivan Šprajc, pp. 34-40. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI), Crystal River, FL. Electronic Document. http://www.famsi.org/reports/01014/01014Sprajc01.pdf.

2004 El origen de la dinastía Kaan. In Los Cautivos de Dzibanché, edited by Enrique Nalda, pp. 114-131. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México D.F.

2005 Toponyms, Emblem Glyphs, and the Political Geography of Southern Campeche. Anthropological Notebooks 11: 87-100.

2008 Monumentos esculpidos: epigrafía e iconografía. In Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste del estado de Campeche: 1996-2005, edited by Šprajc, Iván, pp. 177-232. BAR International Series 1742. Paris Monographs in American Archaeology 19. Archaeopress, Oxford.

Helmke, Christophe, and Felix Kupprat

2017 Los glifos emblema y los lugares sobrenaturales: el caso de Kanu'l y sus implicaciones. Estudios de Cultura Maya 50: 95-135. DOI:10.19130/IIFL.ECM.2017.50.853.

Houston, Stephen D.

2009 A Splendid Predicament: Young Men in Classic Maya Society. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19(2):149-78. DOI:10.1017/S0959774309000250.

2012 The Good Prince: Transition, Texting and Moral Narrative in the Murals of Bonampak, Chiapas, Mexico. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 22(2):153-75. DOI:10.1017/S0959774312000212.

Houston, Stephen D., David Stuart, and Karl A. Taube

2006 The Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among the Classic Maya. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Juárez Cossío, Daniel, and Adrián Baker Pedroza

2008 Intervenciones en Mucaancah y Altar de los Reyes: un acercamiento a través de sus materiales arqueológicos. In Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste del estado de Campeche: 1996-2005, edited by Ivan Šprajc, pp. 131-142. Paris Monographs in American Archaeology 19. BAR International Series 1742. Archaeopress, Oxford.

Kaufman, Terrence

2003 A Preliminary Mayan Etymological Dictionary. Electronic Document. http://www.famsi.org/reports/01051/pmed.pdf.

Landa, Diego de

1566 Relación de las cosas de Yucatán / Fray Di[eg]o de Landa: / MDLXVI. Manuscript. [24-B-68] 9-27-2/5153. Biblioteca de la Real Academia de Historia, Madrid.

Lopes, Luís, and Albert Davletshin

2004 The Glyph for Antler in Mayan Script. Wayeb Notes 11. Electronic Document. https://www.wayeb.org/notes/wayeb_notes0011.pdf.

Marcus, Joyce

1973 Territorial Organization of the Lowland Classic Maya. Science 180:911-916. DOI:10.1126/science.180.4089.911.

1976 Emblem and State in the Classic Maya Lowlands: An Epigraphic Approach to Territorial Organization. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

Martin, Simon

2005 Of Snakes and Bats: Shifting Identities at Calakmul. The PARI Journal 6(2):5-13.

2020 Ancient Maya Politics: A Political Anthropology of the Classic Period 150–900 CE. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube

2008 Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. Thames & Hudson, London.

Mathews, Peter

1980 Notes on the Dynastic Sequence of Bonampak, Part 1. In Third Palenque Round Table, 1978, Part 2, edited by Merle G. Robertson, pp. 60-73. The Palenque Round Table Series 5. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

1988 The Sculpture of Yaxchilan. Ph.D. Dissertation. Yale University, New Haven, CT.

2006 - 2015 The Maya History Project: Deciphering Classic Maya Dates. Manuscript.

Miller, Mary E.

1986 The Murals of Bonampak. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

1995 Maya Masterpieces Revealed at Bonampak. National Geographic Magazine 187(2):50-69.

Miller, Mary E., and Claudia Brittenham

2013 The Spectacle of the Late Maya Court: Reflections on the Murals of Bonampak. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX.

Montgomery, John

2001 Inscriptions of the Bonampak Murals: Drawings by John Montgomery. Department of Art and Art History, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

Polyukhovych, Yuriy

2015 A Possible Phonetic Substitution for T533 or “Ajaw Face”. Glyph Dwellers, Report 33. Electronic Document. http://glyphdwellers.com/pdf/R33.pdf.

Prager, Christian M.

2006 Is T533 a Logograph for BO:K “Smell, Odour”? Manuscript.

2020 A New Logogram for <HUL> “to Arrive” – Implications for the Decipherment of the Month Name Cumku. Textdatenbank und Wörterbuch des Klassischen Maya, Research Note 13. Electronic Document. DOI:10.20376/IDIOM-23665556.20.rn013.en.

Prager, Christian M., and Sven Gronemeyer

2018 Neue Ergebnisse in der Erforschung der Graphemik und Graphetik des Klassischen Maya. In Ägyptologische "Binsen"-Weisheiten III: Formen und Funktionen von Zeichenliste und Paläographie, edited by Svenja A. Gülden, Kyra V. J. van der Moezel, and Ursula Verhoeven-van Elsbergen, pp. 135-181. Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Abhandlungen der Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Klasse 15. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart. DOI:20.500.12030/4980.

Sachse, Frauke

1996 A New Identification of the Bonampak Emblem Glyph. Paper presented at the 1st European Maya Conference: Maya Kings and Warfare at the Usumacinta Basin, London, June 22-26, 1996.

Šprajc, Iván

2003 Archaeological Reconnaissance in Southeastern Campeche, México: 2002 Field Season Report. With Appendices by Daniel Juárez Cossío and Adrián Baker Pedroza, and Nikolai Grube. Electronic Document. http://www.famsi.org/reports/01014/01014Sprajc01.pdf.

Šprajc, Iván, and Atasta Flores Esquivel

2008 Descripción de los sitios. In Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste del estado de Campeche: 1996-2005, edited by Ivan Šprajc, pp. 23-124. Paris Monographs in American Archaeology 19. BAR International Series 1742. Archaeopress, Oxford.

Šprajc, Iván, and Nikolai Grube

2008 Arqueología del sureste de Campeche: una síntesis. In Reconocimiento arqueológico en el sureste del estado de Campeche, México: 1996-2005, edited by Ivan Šprajc, pp. 263-275. Paris Monographs in American Archaeology 19. BAR International Series 1742. Archaeopress, Oxford.

Stuart, David

1987 Ten Phonetic Syllables. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 14. Center for Maya Research, Washington, D.C.

Taube, Karl A.

1988 A Prehispanic Maya Katun Wheel. Journal of Anthropological Research 44:183-203. DOI:10.1086/jar.44.2.3630055.

2004 Structure 10L-16 and its Early Classic Antecedents: Fire and the Evocation and Resurrection of K’inich Yax K’uk’ Mo’. In Understanding Early Classic Copan, edited by Ellen E. Bell, Marcello A. Canuto, and Robert J. Sharer, pp. 265–295. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA.

2010 Cache Vessel with Directional Shells and Jades, 500–600, Copan, Honduras. In Fiery Pool: The Maya and the Mythic Sea, edited by Daniel Finamore and Stephen D. Houston, pp. 266–267. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT; Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA.

Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan

2014 - to date A Working List of Maya Hieroglyphic Signs and Graphs. Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan, Bonn.

2018 - to date Maya Image Archive. Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan, Bonn. https://classicmayan.kor.de.dariah.eu/.

Thompson, J. Eric S.

1962 A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs. The Civilization of the American Indian Series 62. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, OK.

Tokovinine, Alexandre

2008 The Power of Place: Political Landscape and Identity in Classic Maya Inscriptions, Imagery, and Architecture. Ph.D. Dissertation. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

2013 Place and Identity in Classic Maya Narratives. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology 37. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C.

Tsukamoto, Kenichiro

2014 Politics in Plazas: Classic Maya Ritual Performance at El Palmar, Campeche, Mexico. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ.

Tsukamoto, Kenichiro, and Octavio Q. Esparza Olguín

2015 Ajpach’ Waal: The Hieroglyphic Stairway of the Guzmán Group of El Palmar, Campeche, Mexico. In Maya Archaeology 3, edited by Charles Golden, Stephen Houston, and Joel Skidmore, pp. 30-55. Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, San Francisco, CA.

Valencia Rivera, Rogelio, and Octavio Q. Esparza Olguín

2018 La presencia del Glifo Emblema del murciélago en El Petén y el sur de Campeche y sus implicaciones políticas. Estudios de Cultura Maya 51:43-74. DOI:10.19130/IIFL.ECM.2018.51.868.

Wagner, Elisabeth

2006 Ranked Spaces, Ranked Identities: Local Hierarchies, Community Boundaries and an Emic Notion of the Maya Cultural Sphere at Late Classic Copan. In Maya Ethnicity: The Construction of Ethnic Identity from Preclassic to Modern Times, edited by Frauke Sachse, pp. 143-164. Acta Mesoamericana 19. Verlag Anton Saurwein, Markt Schwaben.

Wayeb

n.d. Wayeb Drawing Archive. Electronic Document. https://www.wayeb.org/resources-links/wayeb-resources/wayeb-drawing-archive/#1511686809938-0a32c791-60f6.

Footnotes

-

Download: https://classicmayan.kor.de.dariah.eu/resolve/image_no/NG_IS_2003_ALR_Grube_drawing_Altar3_top

-

Download: https://classicmayan.kor.de.dariah.eu/resolve/image_no/NG_IS_2003_ALR_Grube_drawing_Altar3lateral

-

The fragment has been cataloged by our project as Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3, Fragment 2 (ALR: Alt. 3, Frg. 2) in addition to the remaining main part of the altar, Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3, Fragment 1 (ALR: Alt. 3, Frg. 1) which has been restored from numerous matching fragments.

-

The glyph blocks of Altar de los Reyes, Altar 3, Fragment 2 have been provisionally designated as pX1 and pX2, since their original location within the inscription - either between p3 and p6, or between p9 and p13 - is yet unclear.

-

Download: https://classicmayan.kor.de.dariah.eu/resolve/image_no/IS_2002_ALR_67

-

Download: https://classicmayan.kor.de.dariah.eu/resolve/image_no/ABP_IS_2002_ALR_altar7

-

As part of our work on a new catalog of Maya signs and their graphs, we are currently evaluating and revising Thompson’s Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs (1962). We are critically scrutinizing his system with the help of his original grey cards and supplementing it with signs that were not included in Thompson’s original catalog. Despite its known shortcomings and incompleteness, his catalog is still regarded as the standard work for Maya epigraphers, which is why we adopt Thompson’s nomenclature while removing misclassifications and duplicates, merging graph variants under a common nomenclature, and adding new signs or allographs to the sign index in sequence, starting with the number 1500. Allographs are also further organized with the help of newly defined classification and systematization criteria, which we described in detail in Prager and Gronemeyer (2018). Basically, many graphs of Maya writing can be divided into two or more segments along their horizontal and vertical axes. These segmentation principles are designated by a two-letter code that is suffixed to the sign number. Thus, 1537bl, for instance, refers to a variant of Sign 1537 (hand-with-moon sign) that has been vertically separated into two parts, with only the left segment shown in that context, i.e., the hand without the moon sign (Prager 2020:3, Fig. 4). Revision of existing catalogs and their expansion, including a systematic index of all known allographs of each sign, will form the basis for our machine-readable text corpus of Classic Mayan.

-

In the course of revising previous sign catalogs of Maya writing during by the Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan project, it became apparent that the various graphs formerly subsumed under T756 (Thompson 1962) represent distinct graphemes. In general, their distinct iconic features correlate with distinct phonetic values, which is why they are assigned their own numbers in the revised and extended sign catalog of the Text Database and Dictionary of Classic Mayan project. These graphemes have been cataloged as follows: 756, SUTZ’, 1523, tz’i, 1538, ? (“Copan emblem”), and 1539, xu.

-

Because to date the spelling of transcribed toponyms, including those as part of emblem titles, has not been uniform in the literature, the project has opted for the convention of writing the components of a toponym together in one word, e.g. Bubulha instead of Bubul Ha.

-

Due to bad preservation the exact spelling and arrangement of the Xukalnaah emblem title or toponym cannot be made out for sure in a number of sources, especially in the murals of Bonampak (cf. Montgomery 2001, Houston 2012, Miller and Brittenham 2013). Therefore, only a selection of examples of the Xukalnaah emblem titles and title of origin is presented in Table 1.

-

“Long Count Date of Source” in Table 1 refers to the dedication date of the inscribed monument, or, if no dedication date is provided, the latest date recorded in the respective inscription is chosen and prefixed with “>” to indicate it as a terminus post quem.

-

Download: https://classicmayan.org/portal/editor/uploads/803_twkm_note_21_table_1.pdf

-

A number of hypothetic readings have been presented sofar for Sign 533, which include AJAW, ajaw, “king”, MOK, mook, “maize” (MacLeod and Lopes 2005; Polyukhovych 2015), BOK, book, “smell, odor” (Prager 2006), and SAK, saak, “seed” (David Stuart, cited in Tsukamoto 2014:287), and more recently Albert Davletshin proposed the reading XAK, xaak, “cotyledon, seed leaf” (Albert Davletshin, cited in cf. Beliaev and Vepretskii 2018:7, note 2). The fact that 533 represents a logograph with already two readings AJAW and MOK with clear direct substitutions in temporally and spatially distinct contexts (Polyukhovych 2015), or BOK, a logograph with both initial and final phonetic complementation (Prager 2006), shows the ambiguous nature of Sign 533. The graphs of Sign 533 and iconically similar ones are based on the image of a maize kernel – either as a plain seed kernel or as a germinating one, and all readings of Sign 533 can be attributed to a semantic field that comprises ideas and metaphors based on maize cultivation, that relate to vegetational and human fertility, kingship and descent. Thus, Sign 533 might represent a so-called “concept-sign”, a sign that represents rather a concept and may be attributed a specific phonetic value that depends on the respective context of its use. The now widely accepted - though hypothetical - reading SAK, saak, “seed” by David Stuart (cited in Tsukamoto 2014:287; cf. Prager and Gronemeyer 2018:149f.; Gronemeyer 2019:5; Martin 2020:148, 402-403) fits also very well into the mentioned semantic field.